So you know that opening scene in Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity which ignites Sandra Bullock’s 90 minute fight for survival in the cold depths of space? Turns out that the orbiting debris hurtling around Earth’s atmosphere isn’t the sole domain of fiction and in fact poses a real risk to future space exploration and the existing satellites which facilitate much of the world’s technology. It is these heavenly threats which are the focus of the space debris documentary Adrift from Shooting People co-founder (and my old boss) Cath Le Couteur, and forms part of the wider interactive Project Adrift arts project. I spoke to Cath about the impetus for this multifaceted collaborative project and how she approached documenting an issue of such global proportions within the restrictions of the short film format.

Space junk ranks pretty high on the list of the world’s unseen and ignored problems. What first got you to turn your attention skywards and decide to create a film about the issue?

I knew nothing about space junk. But I was researching another feature film project and I came across the story of an astronaut, Piers Sellers who dropped his spatula in space in 2006, which went on to become a piece of space junk. And I found this very provocative. Here was this mundane, human instrument, orbiting earth as a piece of junk at a dangerous 17,000 miles per hour.. Arguably the most deadly kitchen instrument ever…? And so I delved in more and discovered that astronaut Ed White had dropped a glove in 1965. This image I loved too. A single glove just circling Earth. It was such a lonely image, very melancholic.. and yet also very beautiful and human too. So I was captivated by these very human ‘things’ orbiting the earth and kept reading more. It wasn’t long after that that I became aware of the huge quantities of space junk in existence and how it has now become a significant contemporary crisis. I was grabbed by all of this and by the contradictions the world of space junk expressed.

Clearly this is a global concern which provides countless points of narrative entry. How did you find your way into and then through the subject to develop the film’s structure?

Interesting question because yes, there are so many ways into telling a story about this world. One thing I was clear about from the beginning, was that I didn’t want to tell a straightforward factual, scientific film. That kind of filmmaking approach isn’t my area of personal interest. What I was interested in was the question of whether, we, as humans, could connect with space junk? A world we can’t see, or hear, or even in some instances truly fathom. And I guess I kept coming back to my own responses to the things I’d discovered. I loved how nutty it was that a spatula was pinging around the globe at insanely destructive speeds, I was appalled at the crazy politics of space junk that stops it being cleaned up (countries don’t share information because so much of what they put in space they want kept ‘secret’), I was struck by the pioneering beauty of so many of the objects (a floating museum of space exploration above our heads) which paradoxically have now become terrible things that threaten us, I was grabbed by the melancholic nature of things orbiting around in darkness, and I was curious too about the limitations of science and the limitations of a greedy space industry that can’t see (or frankly doesn’t want to see) that it needs to fund solutions to deal with its waste.

Here was this mundane, human instrument, orbiting earth as a piece of junk at a dangerous 17,000 miles per hour.. Arguably the most deadly kitchen instrument ever…?

In the end, I couldn’t explore all of these thoughts (I had budget only for a short film), so I took as my focus the personal human stories (particularly Piers and his dropped spatula), as the initial way in. The film then grew organically out of that with fantastic creative contributions by my Editors Florence Kennard and Michele Chiappa. What we tried to do was keep the ‘what make us connect to this world?’ at the forefront of our minds. The appearance of Vanguard (the oldest dead satellite) as narrator came right towards the very end of the editing process. I was racking my brains for a way to get across some of the core information, that wouldn’t just entail text on screen. When I decided to try Vanguard as a narrator, it felt quite risky.. Here I was trying to add to a doc, a fictional ‘object’ as a first-person narrator! I worried it might pull people out of the film. Or just not work at all. But at the same time, I myself felt like I had come to know ‘Vanguard’ and know it emotionally! I felt its personal dilemma.. how it might be questioning its purpose and existence. Here it was, heroic and proud, a once hugely revered first solar powered satellite in space. But now, it has become the oldest piece of space junk. A dead satellite, a piece of junk that is now threatening both Earth and space. The animation of Vanguard was created by Daffy London who has done a bunch of pioneering work in VR. It was only after I saw his early beautiful renders that I felt I had the confidence to go for it and make Vanguard the questioning narrator.

Intrinsic to a film such as this is the sourcing and use of archival space footage. How easy was that material to find and was any additional post work required to integrate that footage into the new footage you shot? What was your shooting setup for the film?

Archival was tricky. But the first thing I wanted to do was see if I could persuade Piers Sellers to agree to me interviewing him about his dropped spatula, before I even looked at archival. He was brilliant. He was more than brilliant in fact.. Piers had retired as an astronaut and was working as the Director of the Earth Science Division at NASA. He was a genius climate scientist with numerous awards for outstanding work he was doing in the field of climate change. And yet here I was.. writing to see if I could interview him about this tiny spatula blip… I found his email and wrote cold and he came back straight away with “sure, sounds like fun”. I feel I need to add here that Piers sadly died just before Christmas in 2016 from cancer. He was an inspirational man to so many many people. Even when he was ill, he continued to support the film and he was just an amazing man to be around; warm, insightful, profound and deeply passionate about the fragility of Earth.

Once Piers had agreed to be interviewed, I knew I wanted to find archival footage that would support his story as well as provide lift for other sections. But I quickly discovered that Nasa’s funding cuts have reduced its capacity to easily archive and make easily searchable all its copyright free footage. It’s a total boon of course that so much NASA archive is copyright free. But it’s an infinite labyrinth out there.. I spent days and days hunting for stuff across around ten different NASA websites. I did eventually find some great footage and stills. But most of the footage I’ve used in Adrift, ended up coming from me hunting pieces down via third party news sources (like Associate Press), once I had dates from NASA and a better sense of the exact footage I was after. AP tended to have much longer pieces I could pull from.

I worked with two terrific DOPs; Richard Numeroff for the Washington footage and Constanza Garcia for the Chile footage. We were a very tiny crew and time was tight in both locations so we kept our gear as minimal as we could. In Washington, we shot with the Sony F5 and Canon 50mm prime lens, lit with F&V 2×1 bicolor LED panel. In Chile, we shot with the Canon 5D on a shoulder mount, with a 24-70mm and 70-200mm, and used a Magic Carpet Slider for the timelapses. In post, integrating the archival flowed quite easily. We tweaked the archival colours to match preceding live footage scenes so the piece would have an overall cohesion. The biggest challenge in post was trying to sort out the banding from the archival footage. (Almost all of it was 4:3 and SD!). I was very happy for the archival to look archival in that glitchy degraded way – most of it was after all shot in space! – it needed to keep that vibe… But I couldn’t handle the banding that sometimes appeared when we upscaled the SD/4:3 to fill the frame. My Colorist Susumo Asano worked his Resolve fingers magically to kill the banding. He was also super clever at pulling out particular shadows and highlights in the landscape imagery.

Sally Potter’s soothing voice guides us through Adrift’s cosmic narrative. How did she become involved with the project?

I feel super lucky to have had Sally on the project. Once I had decided to use Vanguard as the narrator, I knew I wanted a mature, female voice that could also capture the emotion of Vanguard. I’d heard Sally speak several times at film events in London and had always found her voice exquisite. Plus I knew she was also an actress as well as a director. So I wrote to her pretty much as soon as I had Vanguard’s voiceover, which was written by the genius novelist Heidi Julavits. Sally came back and amazingly said yes. People are super KIND! If there is anything I’ve learnt in filmmaking – it’s to aim high – because there are wonderful, generous people in the world who you might think are out of reach, but if they like a project, may say yes. Also once Sally had our script, she really improved the personal quality of it, sending us back different versions based on both new research she’d done on Vanguard and also on the way the words sounded to her as she tested reading them out.

This film is part of the larger Project Adrift conceived by yourself and composer/sound artist Nick Ryan. What are the other other elements of this arts project?

Nick and I are great friends and we’ve worked together on previous projects some years ago. When I mentioned space junk to Nick and some of the research I’d come across, he was immediately fascinated with how silent the junk was. Despite it travelling at insane speeds (17,000 miles per hour), the junk is essentially soundless in space. It makes no noise. So Nick, as a sound artist, was fascinated with how he could give a ‘voice’ to all the junk and highlight the crisis through a sound instrument.

We both also have long histories working in and around technology/data in different ways and it was out of a bunch of different conversations we had that our Project Adrift was born. We essentially wanted to create an overall arts project that would allow people to connect to the world personally, audibly and visibly. And so we created three components:

- Watch: the short documentary film Adrift;

- Listen: Nick’s mechanical sound instrument Machine 9 that transforms the movement of 27,000 tracked pieces of space debris into sound in real time;

- Adopt: a spacebot interactive that allows audiences to ‘adopt’ one of three individual pieces of junk by following them on Twitter. Each piece of junk then communicates with you live via Twitter as they circle Earth. The three pieces are Vanguard, Fengyun (born out of a collision in space) and SuitSat (an old Russian spacesuit, pushed out of the ISS in 2006). We developed this component together with computer scientist and artist Daniel Jones, as well as with a group of wonderful writers. The communications are a combination of real live data from the junk, (what town they are flying over, their speed, distance from the ISS, etc.) as well as personal musings. Any of the bits of junk can be adopted @ProjectAdrift.

On the website are also two other mini-films (3mins each), that tell the stories of Vanguard, Fengyun and SuitSat and are narrated by them directly so people can get a sense of each bit. Fengyun has been voted so far as the most ‘Emo’ piece of junk in its live communications, although they are all suffering their own personal crises… All of the components can be seen at www.projectadrift.co.uk and we’re also hoping to tour the project as a whole this year.

Space debris impression

The Adrift exhibition opens at Hackney House, London this Februrary. Could we get a hint of what visitors will be able to experience there?

The Hackney House exhibition is being put on by One Dot Zero and it’s brilliant to be working with them. It’s also a fantastic chance for people to see the instrument LIVE! We’re working on an installation show that will present the instrument, the film and the spacebots in a one-show installation experience which we will continue to tour with this year. For another gallery we also built a hologram that shows all the space debris circling around Earth in real time. You view it through a transparent prism that stands on a plinth. Hidden inside the plinth is a mac and pico projector, that computates all the live data from the debris and projects it out into the prism in the form of a ‘peppers ghost’ hologram. It might be that we expand the project this year as well into other components that interest us – like VR – also a book!

Which of the many creative projects you’re involved in will we see from you next?

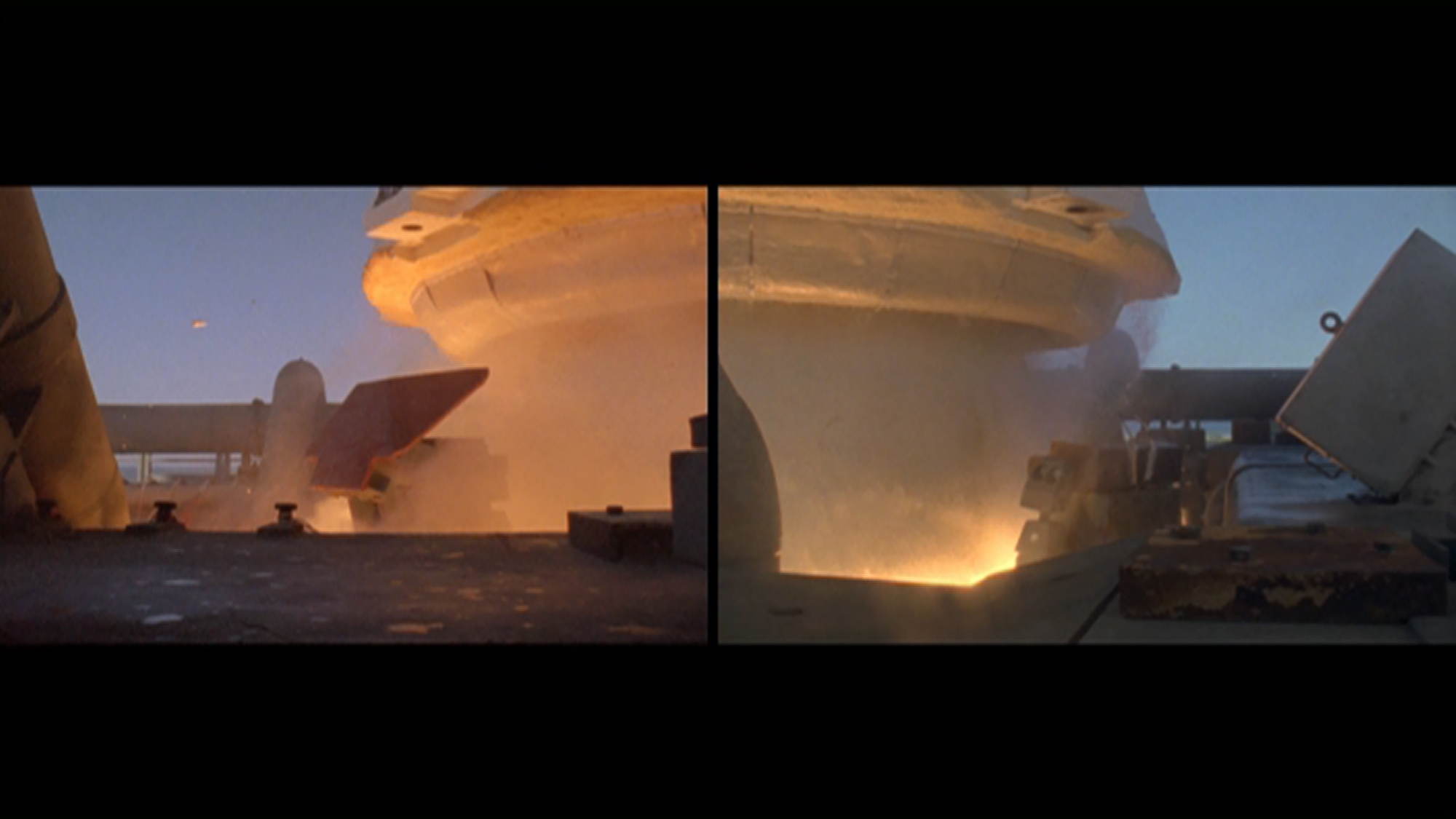

I’m trying to figure out if I should launch into a feature doc version of Adrift. There were so many other stories that emerged from my research that I’d love to explore and probably now is the best time to try and raise that funding. But I’m also attracted to a beautifully dark, magical Poppy Z Brite book I’d love to option and direct, as well as a fiction ensemble film I’ve written about a bed-rest experiment. My main project right now is to explore some of the old-school glass matte paintings from cinema past. I love these illusions and how matte artists used to conjure up castles, planets, vast deserts and other magical creations out of brushes, oils and a sheet of glass. I have no idea where this will take me, but it’s my interest right now.