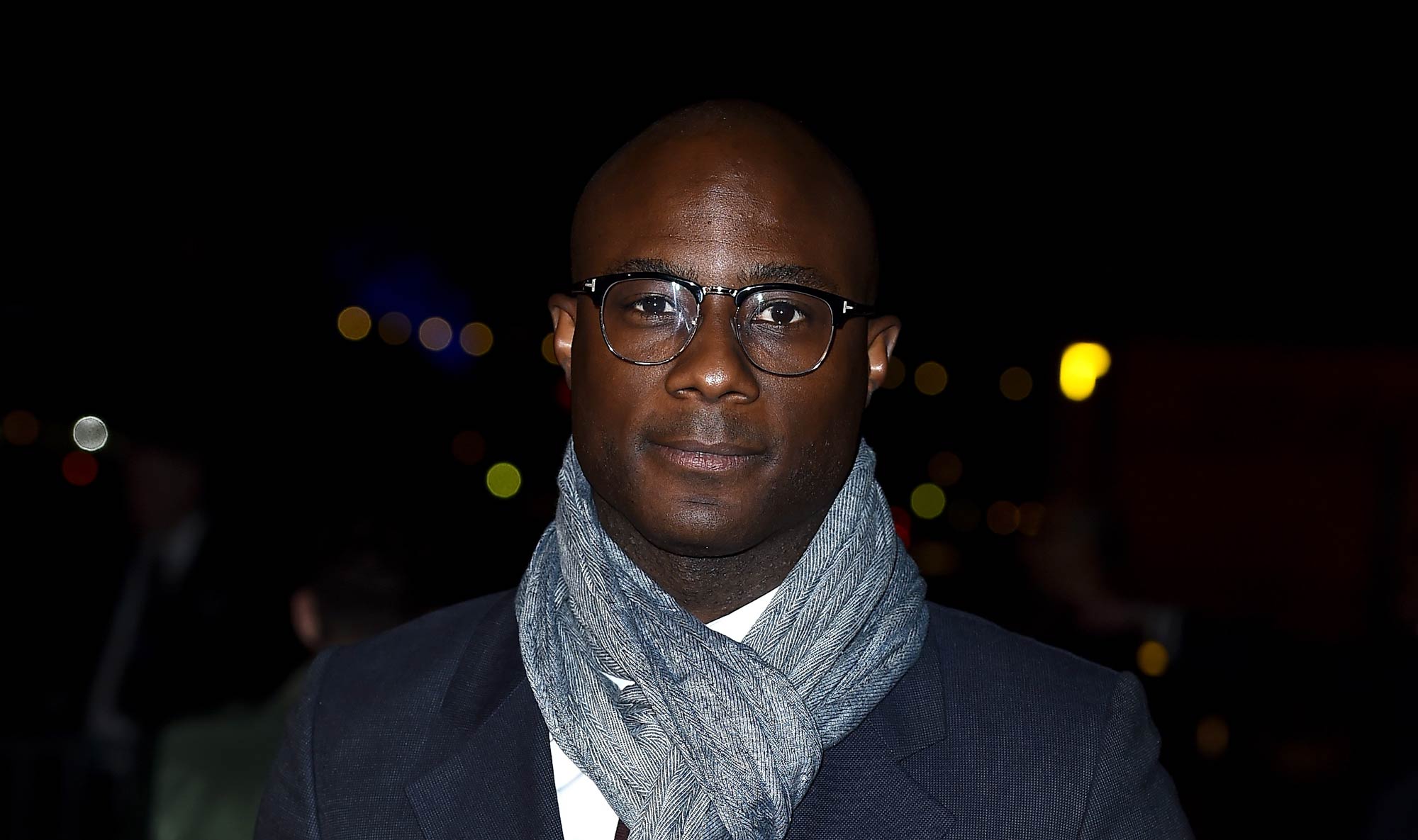

Back in 2008, during my annual excursion to the London Film Festival, I had the pleasure of stumbling across Barry Jenkins’ debut feature Medicine for Melancholy – a film which transformed the familiar ‘morning after the one night stand before’ scenario into an exploration of race, politics, and relationships. Casting San Francisco as an integral character in its own right, the film also featured a soundtrack which felt pulled from the setlist of your favourite alternative club night. With team DN crossing our collective fingers for Barry’s second feature Moonlight collecting on its eight Oscar nominations this Sunday, we return to our interview in which Barry shares his journey from almost school teacher to director and explains why he considered this breakthrough feature his ‘home movie’.

Starting with the obvious question, how did Medicine for Melancholy come about?

You know, it was really a broken heart to make the most simple statement. But, it was also the need to affirm to myself and my friends that we were filmmakers. It had been quite a few years since we had all graduated film school. We were trying to find a way to make a film that we didn’t need anyone’s permission or anyone’s money to be very blunt about it. And so I came up with a very simple concept for this movie, which was a two-hander that allowed us to tackle a traditional dramatic narrative of two characters. At the same time, we addressed the social issues that we thought were important to us in our lives – living in San Francisco and being this generation that I feel are really dealing with a recontextualization of a lot of these issues that have always plagued American society. Mainly issues of class and race and how sometimes that is not the most flattering aspect of American society.

This is your debut feature but you came to filmmaking in a kind of roundabout way? Can you tell us a little bit about how you came to be a director?

I was studying to become a high school English teacher at Florida State University and I guess even then I knew that that wouldn’t be the most fulfilling career for me. So I was walking across campus and I literally saw a sign that said ‘film school’ and for some reason, I just really took to it so I applied and to my surprise, I got in. Even after I got in, I realized that I was in over my head. I couldn’t just become a filmmaker because I necessarily wanted to. So I took a year off from film school and gave myself almost a crash course in cinema.

We were trying to find a way to make a film that we didn’t need anyone’s permission or anyone’s money.

I took a still photography class and I started watching the only films that were available to me at that time, which were these really old and new wave films. These old foreign films that nobody ever checked out of the film library. I really just gorged on that material for a solid year and then when I came back into the program, I made my first short film which was made with a lot of the same crew that made Medicine for Melancholy. I enjoyed the experience so much that I realized this is a way that a) I can express myself and b) I can be intellectually stimulated in a way that nothing had done previously. So it kind of cemented that I would become a filmmaker.

At a recent screening for school kids you basically described the film as ‘just a home movie’?

I’ve never said that before. It was something that I hadn’t realized until two things happened as I was walking over to the BFI. There were all these kids out there riding their skateboards and they were doing all their graffiti and there was a kid standing around with a camera and he was recording them. And I realized it was basically the same camera that we shot Medicine for Melancholy with. And it was pretty much the same amount of people, like a five person crew. In a way, I think it is a home movie. It was just my friends going around and yes we were recording pre-staged scenarios, but at the same time, there’s an intimacy about it that made me, in that moment, want to tell those kids: “You know we made a home movie and you guys way across the Atlantic sat here to watch it. There’s no reason that it can’t happen in the reverse.” These students could make a film, it’s very valid. All the tools that we’re using, they’re all the same.

You’ve name checked Joe Swanberg several times in the past. How much of an influence were his films or at least the approach he brings to filmmaking?

You know it’s funny. I knew who Joe was and I knew how he was making his films but I had not seen one when we made Medicine for Melancholy. I purposely decided to not watch any of those films because I could already tell that there was something going on where people weren’t fairly evaluating those movies on their own merits. I think they were lumping them into this sort of sub-genre that was created. I didn’t want those influences. And really it was the spirit of what Joe was doing that influenced me the most and that inspired me, and that’s why whenever I see him when we’re in a public forum I go out of my way to embarrass the hell out of him.

I think what he did with making those movies, Kissing on the Mouth, LOL, Hannah Takes the Stairs, and Nights and Weekends, Joe was always making a film. You get the notion that nothing can stop him from making films. He’s just going to do that whether anyone feels like he should or should not, he doesn’t care at all! I think that’s the best way to go about this. If the processes are gonna be completely democratized, I think it’s going to be through someone like Joe doing what he does and then folks like me just emulating his process. So even though I hadn’t seen the films, I really had ingested the process of what he’s doing, and that was so inspirational.

Your original sketched scenario for Medicine for Melancholy said that this story could take place New York or Chicago. Yet San Francisco is so entwined into the final film that it doesn’t feel like it could have taken place anywhere else.

I’m glad you said that. It would have been a completely different film. It wouldn’t be titled Medicine for Melancholy. So many of the things that happened in the film just wouldn’t make sense in the city of Chicago or New York. I think that was the beauty of taking so much time between the original idea for the film and actually creating it four years later after I wrote that original line, “Could be set in Chicago or New York”. I think what really made the film go was once we decided we were going to lend such importance to the setting, which is something that I don’t think you see too much in modern cinema, that the setting actually becomes a character.

It’s always about assessing your means and then maximize them, using them until they’re at their greatest limitations.

In fact, there are certain things those two characters say to one another they would not say to each other in Chicago or New York. We tried to make it that specific to the city. I think that’s why we did some of the things we did with the color. Really try to lend a mood to the surroundings and have that be something that people can walk out of the film and instead of just talking about, “Oh, what did he say and what did she say?”, they can say “Oh my God that city, I can’t imagine what it must be like to live there.” Or, sometimes people do say, “You know I really want to go there”, or “I’ve been there and I never got that impression of the city, but it felt so authentic.” That’s one of the best compliments that we’ve gotten about the film.

With regards to the colour, the film has this creamy, mostly desaturated look that blasts back into full colour. Could you tell us about the decisions which led to those choices?

The basic idea was to reflect visually the melancholy that we mention in the title. For James Laxton (the Cinematographer) and I, San Francisco is this place of very muted emotional tones and I think that’s dictated by the weather. Usually when you see San Francisco in films it’s always beautiful and bright and sunny but actually, it’s a lot more like London, in that it’s usually over overcast maybe a little bit gloomy. Then there are these vibrant bursts of color and that was one of the things that we really want to reflect because we wanted to accurately portray the city that we felt we lived in. Also, because this film takes place over 24 hours, there is a mood and a tone to the characters’ emotional states and we wanted to mirror that in the actual image.

We supersaturated the image when we shot the film and then we selectively desaturated it in post. The final color that we ended up settling on, we came to it intuitively. I don’t even know how to describe it? Sometimes I say it’s pink or it’s like this weird orangeish sepia. I have no idea. I just know that once we saw it on the monitor we knew “OK this is where the movie is going to live.” And then like you said, there are some moments where we deviate from that and I think it lends a certain meaning to the color. That’s one of those thing where I always feel that the films that I enjoy the most sometimes, you can mute them and you can still get something emotional just from the imagery. We really wanted this film to play this way even though we shot it with this tiny camera and three or four lights and a five-person crew. We still felt that if we thought about it enough in advance and we really brought some thought and feeling to the aesthetics of the film, that they could really impact the theme. I think when people ask questions about the color that what they’re saying is, “There was something going on there, I can’t really describe it but I can feel it”. It’s one of those things that go into making a film and you hope you can get the same kind of emotional response you put into it. That’s one of the things that’s been very very pleasing.

What equipment did you use on the shoot?

James owns a Panasonic AG-HVX200 camera so we shot on this P2 system. Just because we shot on the HVX didn’t necessarily mean that we were going to shoot 1080 because the camera can shoot 1080i or it can shoot 720p. We shot 720 as it would allow us to do longer takes and to use the memory cards longer without having to change them out and dump the data. We did tests and we realized that even though it wasn’t the highest resolution that the camera could put out, it was the one that we could control the most. It’s always about assessing your means and then maximize them, using them until they’re at their greatest limitations.

So we had that camera and we had this thing called a Redrock micro which is an adaptor that allows you to fix almost like a lens mount onto the front of the fixed lens of the camera. Then we had this really old set of Nikon SLR still lenses that we put on the front of that. So you have this weird very new technology with these P2 HD cards and this very old technology in this set of still lenses from the 60s that all the backing is kind of stripped away, so they flare a little bit differently and they’re very soft. When we desaturated the color I think all those elements came together to give the movie a very specific look. It’s not film but it’s also not video. It’s our HD/still lens look and I think it gives the imagery a quality that’s very unique and specific to the actual project.

For the sound, we actually had a professional sound guy. We did it all on wireless mikes because there were times when we were stealing locations. Excuse me…we were shooting in places that maybe we didn’t have permits for. We would have to have the camera far away and so we used these wireless mikes to really get in there with the actors so there isn’t a boom. That’s actually something that comes from Joe (Swanberg). He likes to shoot very free and the actors can completely move around and there’s no boom. It’s all these wireless mikes and so we adapted those things and brought them into our aesthetic. I think it really helped make the performances very natural.

Although the film was completely scripted, you were fluid enough that as locations changed you could feed that back into the dialogue.

Yeah. One of the funniest moments that we had making the film, our Editor Nat Sanders was cutting while we were still shooting it. So we wrapped after 15 days and he had already cut a solid, maybe two-thirds of the film at that point. I walked into the edit bay and he just gives me this look. He’s like “Man, what are you doing?” I was like “What are you talking about?” He’s like “Man you guys are changing the script so much”. And I was like “No, we’re not changing it. Maybe we’re nudging it here and there, subtly adapting it to these situations that we’re creating in the real time that we’re making the film.” And it’s funny because three months later when we actually premiered the film at SXSW, we were all sitting there watching it and afterward he comes to me and goes, “You know for some reason I thought the movie was changing a lot more than it actually did.”

I think there are two different ways that filmmakers make films. Some people start from a solid point of view and some people start from a question.

He said there was just something about the way the words were coming out of their mouths in these real spaces, that it made it feel like it was a completely different thing than what was on the page. It’s a great comment because I feel like you make a film three times: you write it, and then you shoot it on set and then you edit it. I think every time you do it, it’s a different film. Not completely different, but it should be unique and specific to that medium. It plays one way as a screenplay, it plays another way as you’re on set shooting it, and then it should be completely different as the final product because there are different levels of manipulation that are going on, but hopefully they’re all coercing it into this very unified cohesive vision.

While not polar opposites, the characters of Micah and Jo have very different views on issues of race. Which character is speaking for you and your experiences?

It goes back and forth. Without a doubt, many of the things that Micah says are things that I myself have personally said at one point or another. I can’t watch that scene! Whenever I do sit in on a screening of the film with an audience I get up and I walk out. I can’t watch that. It’s that personal. Like I said, those are things I have said and those are thoughts that I have felt.

I think there are two different ways that filmmakers make films. Some people start from a solid point of view and some people start from a question. For me with Medicine for Melancholy, the starting point was definitely a question. And so I’m not sure which of those characters I identify with more, and I’m not sure which of their views I personally believe in more…it’s very complicated. I go between the two. For me that’s why the movie works because I’ve genuinely felt both sides of that argument and I think if they come across as being authentic and seeming real, it’s because I have genuinely felt both ways and I’m still not sure which one I feel more or less, which one is right or wrong. But I do think they’re both valid and that’s what really makes the movie go. That’s why people are willing to sit and listen to these characters espouse about these very, almost academic things but I think they say them with such feeling that it makes it work.

The soundtrack feels very personal like it’s been pulled from your own record collection.

I’d say 90% of it comes from my collection and only 90% because there were some songs in my collection that I wanted in the film that we just could not obtain the rights to. The music is very personal to me. There was one critic who wrote a review of the film that I thought was just awesome. She wrote this line where she said: “The movie plays like a mixtape movie with smallish indie bands rising up from the periphery to rush us off from one sequence to the next”. Without a doubt that was exactly how I felt about the music in this movie. It wasn’t just something that was in the background, it was really an integral character. When the two characters get on the carousel, that’s when that happens the most, it’s at a peak. I think we took a great risk doing that, I was really worried that it wouldn’t come off. Because it’s so personal to me I want it to be personal to the characters and to the film. I think it works. I’m glad you asked that question, I never get that question and it is something that was very important to me, to have the music be an integral part of the film.

Have you got your next project in your sights?

There is a literary adaptation that I’ve always been interested in and now that this movie has come out and gone around I might actually get the opportunity to tackle that film. It’s grander in scale and it requires an actual budget and things of that nature. It’s about the American dream as told from the immigrant’s perspective. I think it deals with some of the same issues as Medicine for Melancholy but with a much more interesting narrative, not so simple and with more mature characters, which are things that I’m very interested in tackling. Hopefully that’ll come about but for now, I’m still riding the Medicine train.

This interview was taken from our podcast recorded with Barry Jenkins at the 52nd London Film Festival.