Starring well regarded character actors Stephen Tobolowsky and DJ Qualls in a shifting game of cat and mouse, Paul Schneider’s Fifty Minutes sees a successful therapist negotiate for his life when a vexed patient draws a pistol. In our interview, Paul shares how he recontextualised the internal perspective of the original short story into a tense onscreen battle of wits between a desperate pair of unreliable adversaries.

Where did the idea for Fifty Minutes originate?

Fifty Minutes was adapted from a short story of the same name written by author Joe Donnelly and his therapist, Harry Shannon. It was originally published by Slake in Los Angeles before being featured in The Best American Mystery Stories of 2012. I came across this story in 2013 when my friend and producing partner, Roberto Alcantara recommended it. Being a huge fan of mystery, thrillers and dark comedy, I was immediately hooked on the story. It was smart, crafty and intense; my kind of tale with my kind of energy.

Was there a particular take on the material that you approached the authors with to secure the rights and their participation in the project?

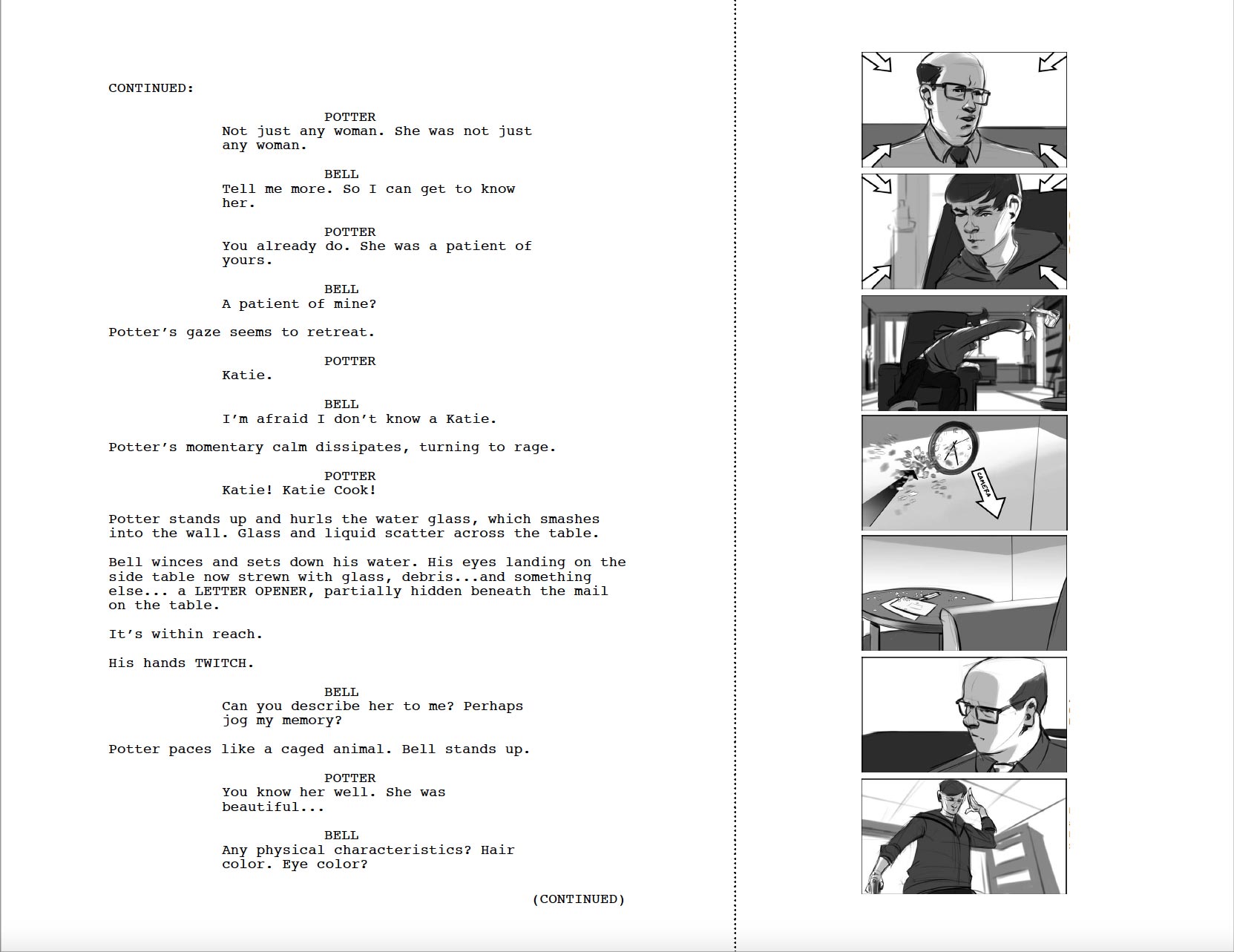

The original story took place exclusively from the therapist’s point of view, when approaching the authors my pitch was to take it out of the doctor’s head and create a dynamic film-able confrontation between the characters. When I took my ideas to the authors the Buddha was a footnote in the basic layout of the office; part of my initial discussions with them was to make a character out of the Buddha to infuse an omniscient third party, a witness to the scene. The Buddha would add the necessary third character to break up the tense interactions between the therapist and his patient.

Another aspect we discussed is the idea that the audience is receiving their information exclusively from mysterious and flawed characters. There is an intentional lack of character development inherent in the original story to maintain the mystery of which character is good or evil. We worked with the authors to draft several possible versions of the story, but it was ultimately the addition of screenwriter Amanda Glassman that allowed us to craft a workable screenplay; finding the right balance of tension and information.

Casting Stephen Tobolowsky and DJ Qualls in this two-hander short is quite the coup, how did you get them involved?

What can I say about the casting? I really wanted experienced, seasoned performers to embody these characters. Stephen Tobolowsky and DJ Qualls were my first choices and this being my first real film we sent them each the script emboldened by a combination of naiveté and wishful thinking. To our pleasure and surprise, they both said YES! As a director I admired their professionalism, talent and pure dedication to their craft. Together we established a relationship conducive to the improvisation and enhancement of the characters, while being true to the story.

I imagine their schedules severely limited the opportunity for rehearsal time. How did you therefore ensure you were all working to a cohesive vision during the shoot?

Stephen and DJ work constantly and it was very difficult to reconcile their timelines, but after reviewing the material (and before I could even ask) they both reached out to insist on a group table read. The script was approximately 20 pages of rapid-fire dialog, and the proposed two-day shoot schedule made it very apparent that practicing together was critical in getting the beats right. To facilitate this, we scheduled our shoot a few weeks into the New Year, which is typically a very slow production time in Los Angeles. About a week before the shoot, we met to read the script aloud, make adjustments, address concerns, and to get acquainted. This was a wonderful opportunity because I was able to convey my specific thoughts and desires for the film. Each actor brought a unique perspective to their character, and their combined experience and wisdom enabled us to have a very creative and productive rhythm.

Given the spacial limitations of the therapist’s office, how did you block out the action to ratchet up the tension as well as maintain visual interest?

I was attracted to the intensity created by the dynamic dialog between two mysterious characters confined to an inescapable space, and I knew that if executed correctly it would make for an intriguing experience for the actors as well as the audience.

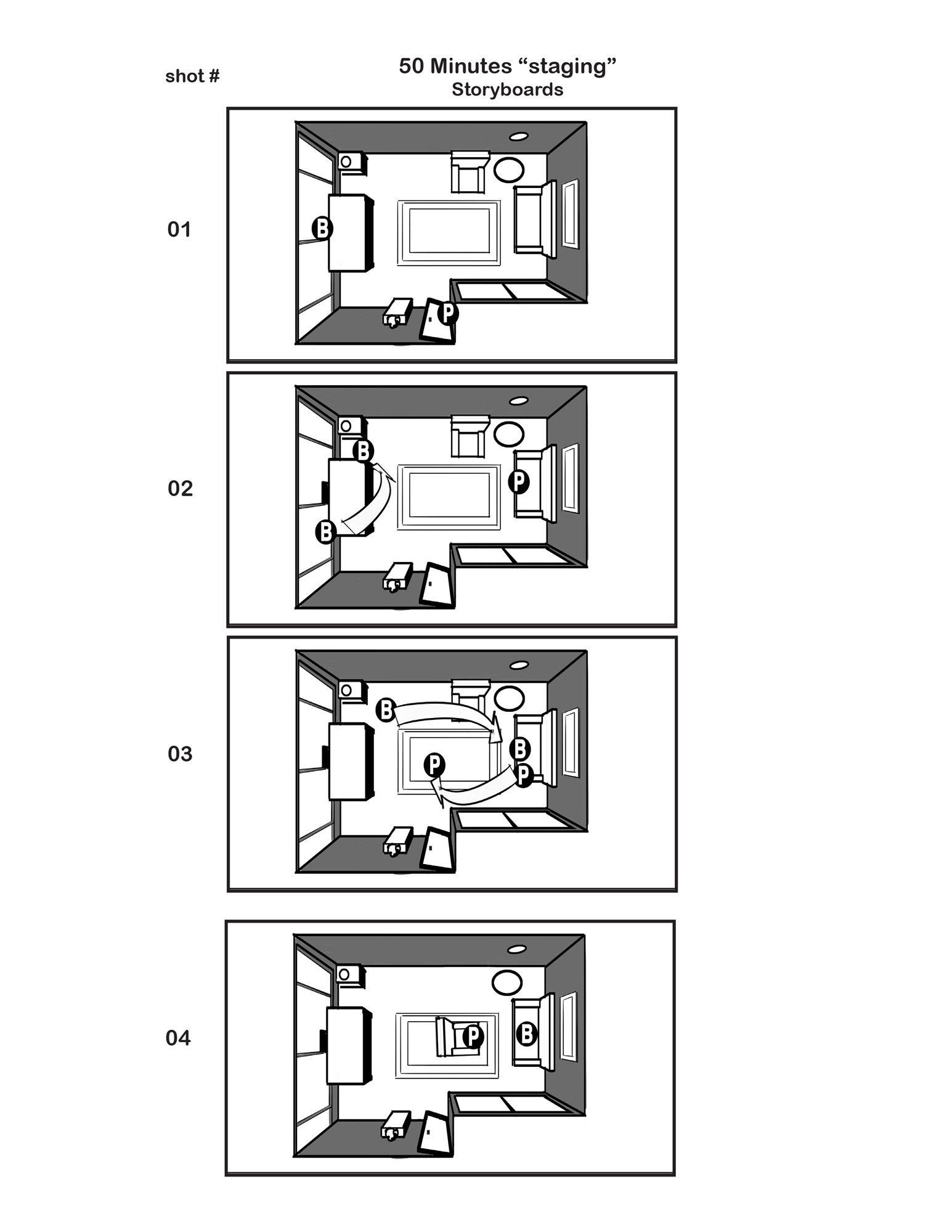

While developing the screenplay I tried to envision the office space as more than one location in order to provide more visual variation. I broke up the office into areas; the doctor’s desk, doorway, couch, Buddha and water station, which allowed us to create distinct and separate scenes within a singular space. I knew that by doing this we would have less flexibility in our edit, but the overall visual scope and storytelling would be greatly enhanced.

I tried to envision the office space as more than one location in order to provide more visual variation.

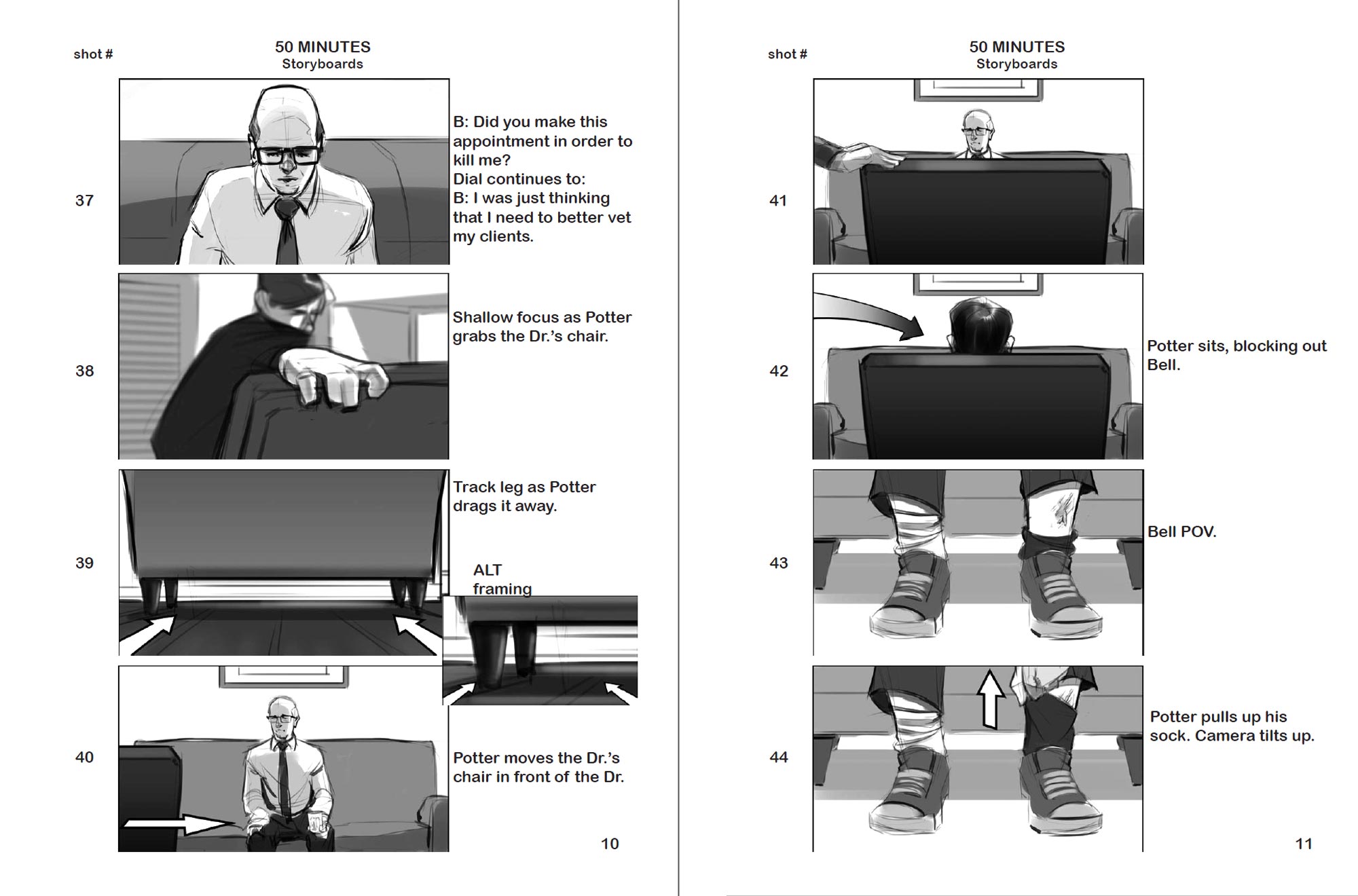

I worked with a storyboard artist to create a roadmap for the film and specific blocking diagrams for each scene. Our short filming schedule and hand held shooting style (using two Sony FS7 cameras with converted stills lenses from the 1970s) meant that there would surely be variations to the storyboards, but the act of breaking the movie down into individual frames allowed me to go into the shoot with a great deal of confidence about where we would need to be at any given time.

The day before we physically shot we met at the location with key crew members for lighting and for art department to prepare the space, but it also proved to be a great time for the actors to come to rehearse and practice blocking and performance. Using the storyboards as their guide, DJ and Stephen would practice each scene in order to develop their performance in relation to the actual space. Throughout this day Cinematographer John Zilles and I were able to scout camera positions and plot movement designed to highlight the tension within each scene. Everyone walked in on the first day knowing where and how we would start, this created an environment where the actors were comfortably able to immerse themselves in their characters.

Things turn physical as the confrontation escalates, could you share how you went about making the fight scene both convincing, yet safe for those involved?

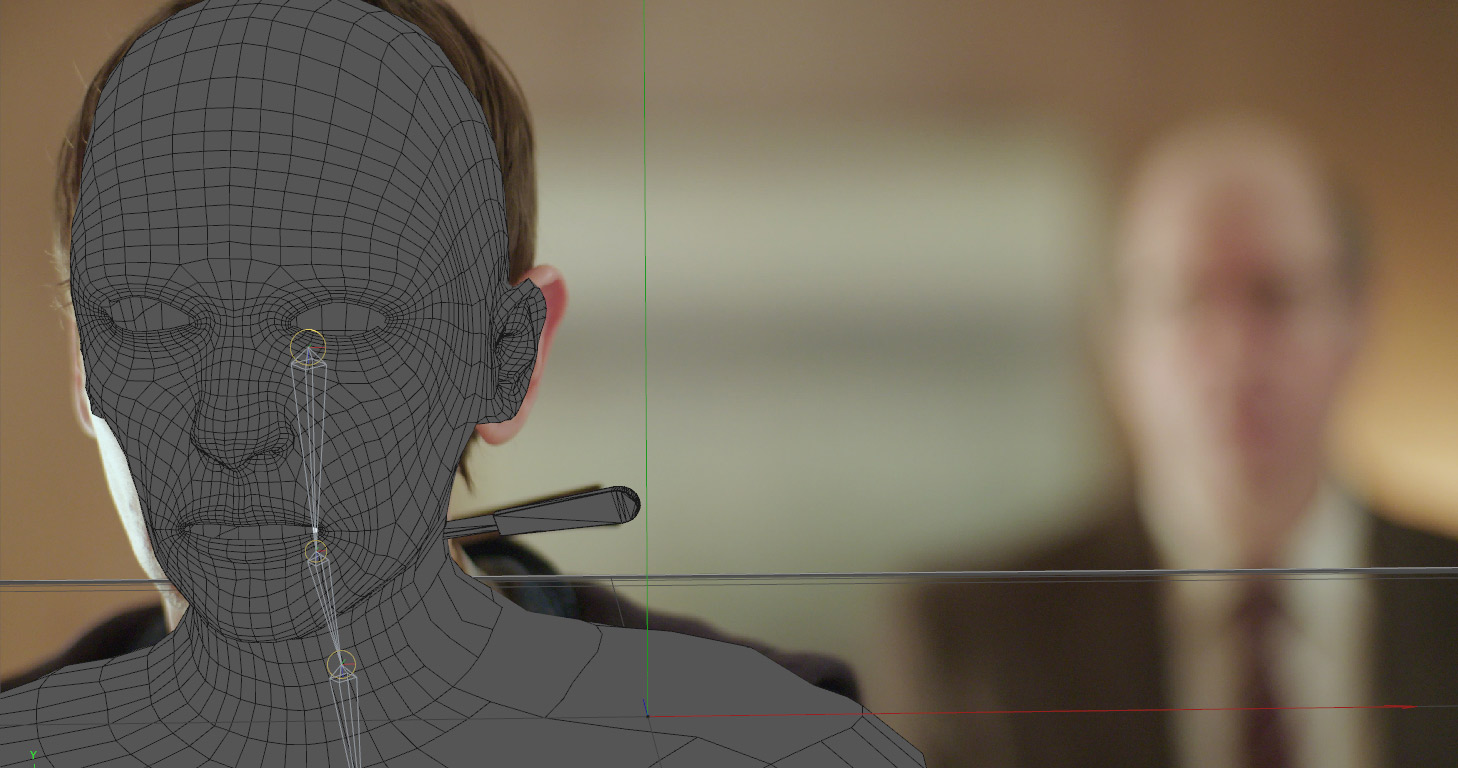

Although it looked intense, there was no danger to the actors, but due to the physical nature of the fight scenes, we saved them for last to preserve the actors’ energy as well as costumes, hair and makeup. Before filming we took some time to choreograph the struggle and to plot out the relationship between camera and performer to create authenticity. Our cameras would rotate around the actors, which increased the kinetic motion of the action, making the struggle for the gun look very physical. We captured it from a multitude of camera angles and focal lengths, including some extreme closeups in order to enhance the action.

Fifty Minutes has some fairly violent scenes but most of the elements that would make this dangerous were added in post production. The knife (letter opener), the bullet holes, and shots fired from the gun were all added and composited separately. Normally these effects would be expensive and time consuming, but working on a limited budget I pulled from my past experience with visual effects and was able to complete them with the help of a few friends.

What do you have lined up for your next project?

I direct commercials regularly and am currently in development on an independent feature film.