Taking a non-judgemental, vérité approach to the highly contentious and politicised subject of American mass gun ownership, JJ Walker’s docu-style music video for St Francis Hotel’s You’d Gotta Be Alive provides an undogmatic portrait of the people and places that make up the beating heart of US gun culture. DN invited JJ to share how he navigated an accidental shooting and ricocheting bullets for this Rifleman’s creed inspired 35mm project.

The project was originally conceived as a short documentary exploring the culture of gun-ownership in the United States. The plan was to profile gun owners and structure it around the U.S. Marines’ Riflemen’s Creed, which famously starts: “This is my rifle. There are many like it, but this one is mine”. Not being very knowledgeable about gun culture myself, I spent several weeks researching firearm-related hobbies and events, including gun shows and the shooting sports.

As development continued, I realized my approach was from less of a journalistic angle and more of a visual exploration of this subculture. I sensed there were opportunities to photograph some powerful imagery, and if paired with the right music, could combine into an impactful piece of work. With some serendipity, I stumbled across a song from St Francis Hotel, an Irish musical duo based in London. Their song, You’d Gotta Be Alive, had an energy and vibe I was hoping to achieve with the photography. I took a step back and imagined the project as a docu-style music video, instead. I reached out to the musicians, and luckily, they responded positively to the project.

Because of the low-budget, traveling was limited. Locations were narrowed to the central Oklahoma region. For me, this seemed to be the heart of gun culture in the US, and because I had family living in the area, there was a local connection that could be beneficial during the planning and pre-production stages. We had a week-and-half available to film, and travel was restricted to a radius of a hundred miles of where we were staying. Many of the locations were found with some trusty internet sleuthing, or reaching out to contacts and family members that lived in the area. It was then about following the trail to see where it would lead. Luckily, there were many firearm-related events at the local gun clubs and ranges to choose from.

It was eye-opening to discover this world around you that you didn’t know existed.

It was with the help of a family member’s co-worker that I discovered the sport of Cowboy Action Shooting. These sportsmen and sportswomen spend thousands of dollars on their guns, ammunition, and outfits to identify with the sharpshooters of the American Frontier. They even recreate the atmosphere of this period by constructing ’Old West’-themed stages. Immediately, I was confident this sport could offer some distinctive imagery for the film.

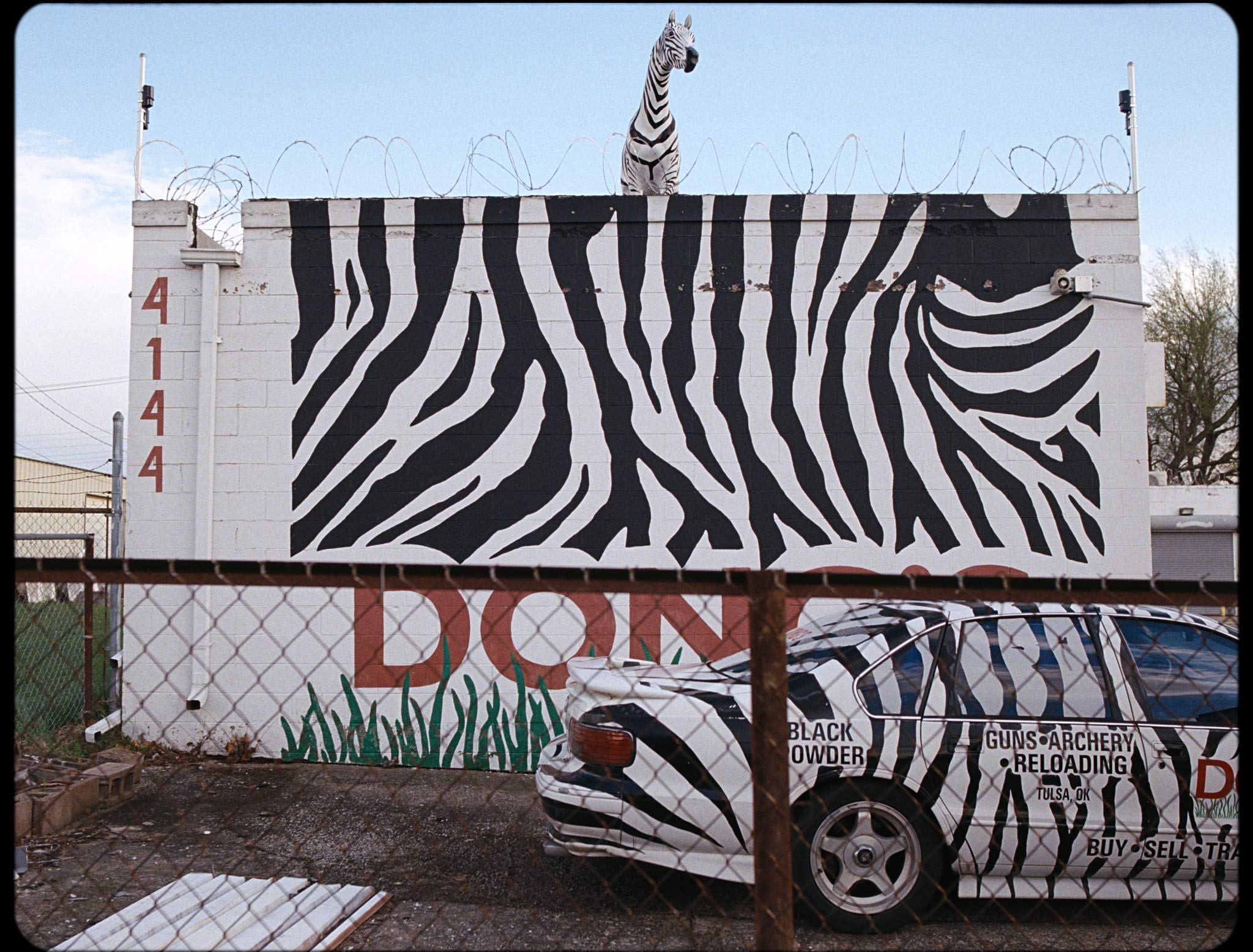

Some minor locations, such as the roadside attractions, were found while cruising Street View on Google Maps (for instance, the Happy Burger restaurant seen in the film). This can be a surprisingly effective method for scouting remotely, when appropriate. In another instance, we used a ‘neighborhood app’ to find a nearby hobbyist who uses the machinery in their home garage to reload bullets (the process of inserting gunpowder into bullet shells). As with this, and other cases, it was eye-opening to discover this world around you that you didn’t know existed.

Much of the remainder of pre-production was spent securing filming permission for the many locations seen in the film. The process usually involved several back-and-forth emails or phone calls — or both. From the start, it was important to be open and straightforward when approaching contacts. I made my intentions clear: the goal was to create an unbiased and non-political project on gun culture. Most people responded positively, and if there was any hesitation at first, they eventually warmed to the idea, welcoming the opportunity to share their passion with others. Not to say there weren’t a few rejections, whether it was a nicely worded email, or in one instance, a rather threatening phone call. But overall, people were very gracious with their time and participation — and I’m very thankful for that.

Not all the schedule and location decisions were finalized during pre-production. I wanted some flexibility after I had ‘boots on the ground’, as the best discoveries seem to happen then. For example, after visiting a few shooting ranges, I acquired many paper shooting targets with varied designs, ranging from the iconic human silhouette to photographic depictions of real-life scenarios, such as a hostage-taking. After some brainstorming, I realized there could be opportunities later in the edit to reveal and contextualize these images in unexpected ways.

Once production commenced, I was reminded that going out into the real world brings its surprises. On the first day of filming, we visited a large gun show. There was an accidental shooting that day that earned local news coverage. A security guard clumsily discharged a gun he was handling; the bullet ricocheted and lodged into another guard’s hand. This was a reminder that anything can happen when a crowd of people and firearms are around.

My first experience filming at a live-fire event was a Cowboy Action Shooting competition. As advised, I wore protective eyewear and earplugs. Moments into filming, I felt a sharp sting near my groin. I was fearful something had gone very wrong. After a few anxious moments, I realized what others had failed to mention: there was a high likelihood of getting pelted by the ricochet of the bullet when standing near the shooting action. Fortunately, there was no harm done, and with some experience I became more comfortable being near to the action. But I did make sure to always have a filter in front of the camera lens.

Moments into filming, I felt a sharp sting near my groin. I was fearful something had gone very wrong.

From a creative standpoint, my goal was to create an observational, ‘visual diary’ of the people and places I encountered while exploring this subculture. I drew inspiration from many well-known street photographers, especially the medium-format work of Martin Parr, who had an amazing eye for people in their surroundings. The squarish proportions of the 6×7 format encouraged me to photograph in the 1.33 aspect ratio. I felt it could allow a more respectful and classical composing of the portraits, and give a more expansive window into the scene — akin to the human eye.

With this approach in mind, I embraced the simplicity of the handheld filming style. I chose to photograph most scenes in a practical manner — from the perspective of a person standing there, observing the scene from their point-of-view. Most shots were composed straight-on, centering the subject, as if they and the viewer are in a stand-off of sorts. I tried to embrace the natural lighting that was available, but did use a reflector on a few occasions to bring in more light to the scene.

The entire project was photographed on 35mm film. I sensed this format could provide the detail needed to insert the viewer into the scene, while still giving a touch of grain that felt appropriate for the style and subject matter of the project. Also, the organic characteristics of celluloid seemed a good match for the qualities and timbre of the music, especially the prominent fuzzed-out guitar. Digitally-captured imagery has a tendency to feel very clean and almost glossy, and doing any ‘post-trickery’ on the footage felt dishonest, considering the tone I was trying to achieve. Being a first-time shooter on film did bring its risks, but this project was about risk-taking — which is also imbued within its theme being firearms.

For the camera setup, I filmed with an ARRI Arricam LT paired with a Zeiss 25mm lens. It’s a wide-to-normal lens on the 35mm format. I felt establishing this consistent perspective would help in immersing the viewer into each scene, and from shot to shot. From the scanning through delivery, the image was purposely left un-cropped, leaving a black border around the frame. Paradoxically, I found being aware of this border helped the viewer to feel closer to the photographed environment, as if the frame is now an opening into the scene and the viewer is left feeling a bit exposed and vulnerable.

A big nuisance when shooting on film cameras can be the battery situation. Unlike digital cameras, film cameras are essentially mechanical machines that need some hefty batteries to run. The weight of this camera and lens is around twenty-five pounds. To manage the weight on my shoulders and keep the rig balanced, I wore two batteries around my waist. I noticed cinematographers who often shoot from the shoulder, such as Sean Bobbitt, B.S.C., were using this same setup.

Doing any ‘post-trickery’ on the footage felt dishonest.

By design and necessity, the production crew comprised of just two people, myself and an assistant, William Bettge. While he had no prior experience assisting on a shoot, he was very helpful offering a much-needed shoulder to rest the camera on during breaks, keeping a watchful eye on the film counter, and carrying any necessary filters. I used a basic set of ND filters, along with a set of 85ND (warming) filters for converting the tungsten stock to daylight-balanced when needed. Having a two-man crew allowed us to be more mobile and draw as little attention to ourselves as possible, which was a necessity.

Shortends and recans (leftover film stock from other shoots) were acquired from resellers in the US and UK. The specific stocks used were Kodak Vision3 200T 5213 and Vision3 500T 5219. For the project, I shot just under 2,400 feet of film. This is around 24 minutes (filming at 4-perf), which is a tight shooting ratio — even for a four-minute music video. I needed to be disciplined with my shot selection, a limitation I embraced. By considering the final edit — and whether a shot would ultimately be useable or not — made the piece stronger in the end, I believe.

For some locations, I would choose only one or two scenes to photograph. I remember after walking around for nearly an hour at a gun museum, a vast building filled with rows and rows of firearms, I chose just one scene to photograph: a TV showing a dated, VHS recording of a gun-stock assembly workshop. This careful selection of shots made combing through footage during the assembly edit a more focused and enjoyable experience.

Every shot in the film was photographed at 24 FPS. There was a temptation to film some specific moments at a higher frame rate, but I realized the speed of these real-life moments is a powerful component. Whether it’s a shooting competition that determines who has the greatest accuracy and quickness — or any general incident involving a firearm being discharged — it’s surprising to witness how fast the action unfolds in real-time. It can feel like it happens in the blink of an eye. In several instances when filming a “Steel Challenge” event (a competition where participants shoot at a series of steel targets with a handgun or rifle), by the time I pushed the ‘run’ button on the camera, the burst of fire had finished.

After production wrapped, the 35mm footage was sent to FotoKem in Los Angeles for processing. It was then scanned at 4k resolution on the DFT Scanity at nearby Cinelicious. They sent back ‘ProRes 4444’ files, which I edited and finished in DaVinci Resolve at 2k. The file sizes were very manageable, less than 500 GB total. The challenge was color-correcting the footage which comes back appearing flat, similar to digital video shot with a ‘log profile’. After a few restarts, I was able to get the footage balanced and neutral, but this was the most time-consuming part of post-production since I hadn’t graded film footage prior to this project. A quick tip is to keep a quality ‘film print LUT’ at the end of your node chain and do any corrections before this final node.

Some filmmakers contend that because the post-production pipeline is now entirely digital, then it only makes sense to acquire the footage digitally. I could argue the opposite, that because projects are now finished digitally, it can be useful to start with an analog capture medium to infuse the footage with some texture and warmth — and thus, some life.

It really is a great time to shoot on film.

With powerful color-grading software becoming more affordable, if not free, along with improved scanning technology, it really is a great time to shoot on film. Admittedly, video compression on the web has been brutal to celluloid-based footage in the past, but improving codecs and bandwidth are bringing out more of the beauty of the film grain. It now comes down to choice — which is the way it should be, right?

In the end, it was satisfying to see the final, graded footage layered with St Francis Hotel’s haunting song. It’s a powerful pairing, I feel. The artists were pleased with how the project turned out and wanted to promote it as an official music video for the song. They mentioned how the film had given their song a new perspective and angle they hadn’t imagined, and, as was my goal — appreciated how it was impartial and allowed the pictures to tell the story. As an emerging musical duo with an exciting future, I’m thrilled to have had the opportunity to bring some new ears to their music.

During the process of the film’s creation, I was continually reminded of my own background as a designer and visual artist. Music videos offer such a large canvas to explore visual ideas related to the meaning and vibe of the music (along with the intentions of the music artist and their own aesthetics). I hope to have more opportunities in the future to explore and experiment within this medium — and have some fun doing it.