On the surface Alfie Dale’s My Brother is a Mermaid may seem about something quite extraordinary, however, this social-realist fairytale is actually more subtle than you might expect. Dale’s short drama about a trans-feminine teen and their brother tackles society’s embedded gender norms on a profound spiritual level as opposed to a physical one, a space which a lot of on screen representation for trans characters occupy. Dale crafted his unique tail (pun intended) through a series of improvisations, unbeknownst of where the story would head. The result of which is a genuinely refreshing and moving portrayal of gender politics, which we’re delighted to premiere online today. We spoke with Dale about re-understanding gender, moving past social constructions and his evolving creative process that conceived My Brother is a Mermaid.

What were the key pieces in putting together the story for My Brother is a Mermaid?

I had a few scattered ideas that ended up coming together for Mermaid. I’d been wanting to do something about siblings for a while, I have a younger brother with a similar age gap to Kai and Kuda, and wanted to explore that relationship in my work. Then, when I was in Madagascar, I went surfing with these two brothers who were local surf guides, in quite a remote part of the country. We had a drink after, and when we were chatting I jokingly asked if they had any mermaids around there? The younger of the two looked at me surprised, and said: “So, mermaids are real?” I guess that whole situation played a significant part in the idea!

The transgender narrative came about because I’d been reading a lot about gender at that time, and a lot of my headspace was focused on re-understanding gender. I think I had viewed the world and myself in a pretty gendered, binary way up until that point, as most people do. Reading about how socially constructed gender is really helped me reframe my understanding of the world and myself. Throughout my teens and early twenties, I think a lot of what I disliked about myself was down to a sense that I was failing to live up to what a ‘man’ should be, or that I naturally didn’t have the qualities that make men valuable. This was obviously a ridiculous way to think, but was a lot of the background noise going on in my head!

Reading about how socially constructed gender is really helped me reframe my understanding of the world and myself.

So, when all the media, articles, etc. started coming out around 2014 or so, bringing a lot more profile to trans people and taking the time to explain what it really meant to be trans, it really resonated with me and was quite liberating. From birth, we’ve all been duped into thinking there’s a ‘right’ way for women/men to exist, and that we all must identify as one of these things. It’s deeply ingrained, the idea that biology at birth should determine your character, how you are treated, and how you live your life. It takes quite a bit of work for a lot of us to become aware of how silly it is because it’s so embedded.

Did that moment in 2014 provide a lot of the underpinning of what went into the screenplay?

Having so much media available, from and about trans people, gave me a way to do this work, and I’m deeply grateful for that. That’s why I think stories about transgender people of all sorts, are so important, benefitting trans and cis people alike. They help a lot of trans people know they are seen, loved and not alone, and help cis people understand what it is to be trans. But also, they can help all of us break down the gender issues in our own lives and understand how we’ve been inhibited and hurt by the gender expectations put upon us. Overcoming the idea that your gender should determine your life, is a personal, internal revolution.

That’s where the idea came from and why I wanted to tell this story. I just thought that with so much ‘debate’ in the public sphere about someone’s right to exist authentically, with so much focus on the physical side of being trans, I wanted to tell a story that was more about siblings and their bond, and how to them gender is just a non-issue. Kai is a mermaid… the gender part of that doesn’t interest Kuda. He sees Kai’s soul. Berwyn Rowland, director of the Iris Prize Film Festival, said that what he liked about the story was that it focussed on Kai in a spiritual sense, rather than focusing so much on their physicality.

After you created the concept, what was the next step in production?

Straight after the idea crystallised I Googled ‘transgender mermaid film’, and the first thing that came up was the charity Mermaids which happens to be the UK’s leading youth trans charity. So, I called them up to see what they thought of the idea if they thought it was okay for me to make the film, etc. They were incredibly supportive and got really involved, helping with casting, making sure we had a trans actor for the trans character – although we actually found Cameron Maydale through our brilliant Casting Director Sue Odell – and giving a lot of ongoing feedback on the script through the rewrites. I was super lucky to have them involved, I wouldn’t have made the film without them. All filmmakers should have the mantra “nothing about us without us” tattooed. This film wouldn’t have been as good if I’d just tried to do it myself, without the input of Mermaids, and the lead, Cameron Maydale, who also contributed a lot to the development of the script and character.

There are a variety of locations and you shot in the sea too, did that complicate production?

It was a tricky production and pretty unconventional. We shot on four weekends over the course of a year. The ‘plan’ was to shoot a bit, then rewrite the script in response to what was shot, and use the footage to raise more money for the next chunk of the shoot. To call it a ‘plan’ is a bit generous… that’s just what ended up happening! We had planned to get it all done a lot quicker, but funding and script rewrites and day jobs slowed things down. So, there were a lot of crew along the journey, often new people for new chunks of the shoot, all of whom I couldn’t be more grateful for.

What did you shoot first?

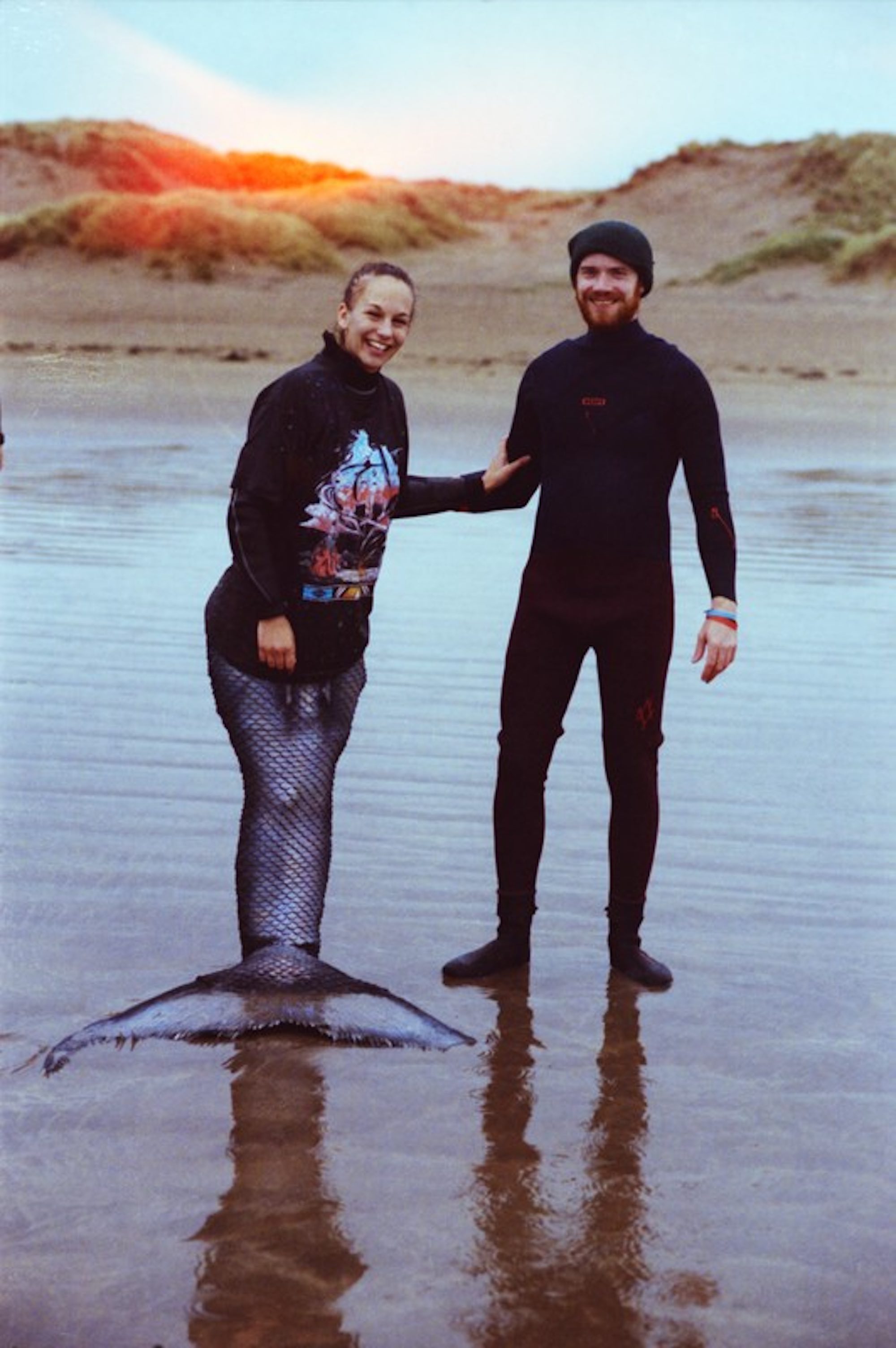

The first thing we shot was the beach footage, this was quite rushed as the film was conceived in late July, then we realised that once the sea got too cold by mid-October, filming would be impossible until the following year. So, I wrote as much of the film as I could and we ploughed forward to get the beach/sea shots ASAP. This actually turned out to be one of the most enjoyable parts of the shoot, the crew were really tight and we all stayed in a lovely cottage we somehow managed to borrow from a friend for free. Filming in the sea was exciting, and the beach was one of the most beautiful I’ve ever been to. It was really windy, so all the kite surfers came out and added an incredible backdrop to the beach scenes. It was a lot of fun.

Originally we had planned to film all the underwater footage at the beach, as we didn’t think we could afford a tank… the intention at this time was to make the film quite naturalistic, with Kuda and the audience just seeing glimpses of mermaid tail, never getting a full on view. The issue was that the water was sandy and we couldn’t see a thing underwater. So, we had this stunt mermaid in her tail, being carried across the beach by lifeguards, splashing around in freezing water, and we couldn’t see a bloody thing on camera.

Searching for the cheapest option for everything, bartering for everything is exhausting… but it’s the only way to make a film of this scale for this budget.

We decided we’d have to find a way to shoot in a proper pool. Which obviously worked out way better, and meant we could get proper underwater shots, in a sort of magical underwater realm. We shot in this big diving pool that was really cheap, and the DoP Jim Petersen and Gaffer Sabrina Corder nailed it with the underwater lighting. I was worried that Aidan and Cameron would struggle with the underwater performance and keeping their eyes open, but as ever they were determined to make it work, and they were amazing.

Did you have to use any specific camera equipment to capture that?

Most of the film was shot on an Alexa Mini, including the footage in the sea. But the underwater housing for the Alexa was quite expensive and difficult to work with, and our kit budget was going down every shoot! For the underwater pool footage, we switched to Jim’s old FS7 for which the underwater housing was way cheaper and easier to operate.

The whole thing was shot on a shoestring, other than the pool we didn’t pay for a single location, and the pool was incredibly cheap! Producing on a low budget like that is a whole other beast, we had to search really far and wide for locations that were suitable and we could use for free. It also meant that if crew had full paying work come up last minute, they’d often have to take it, so there were a few midnight scrambles to find replacement crew the night before a shoot. Searching for the cheapest option for everything, bartering for everything is exhausting… but it’s the only way to make a film of this scale for this budget.

So much of the film rides on the relationship between your actors, how did you work with them to develop their arcs?

Building that bond with Aidan and Cameron was really the focus of our limited rehearsals. They got on so well in real life, that it all felt really authentic, and it was just about letting that natural warmth between them grow. The characterisation was really built around who they are as people, it’s the only way to do it I think with untrained actors. They create the character and the writer/director has to work with and respond to that. Then on the shoot, some parts were very conventional and structured, but a lot of it was shot more documentary style, which Jim and Focus Puller Andrea Clavijo were great at.

I love finding those moments where it’s real.

What worked was letting the actors play until they forget they’re on a film set, then occasionally throwing in ideas just nudging them in the right direction. It means you overshoot a lot, waiting for those really authentic moments, so the edit was a bit of a beast to work through. But I love finding those moments where it’s real. That’s one of the best things about working with kids, when they forget the camera’s there and get lost in the story, it really is real. Aidan was himself questioning the existence of mermaids whilst filming, and working out the world. There was a lot of genuine wonder in him. In the audition, he’d responded really well to direction, it was clear that he listened and could transport himself to a place where it felt real to him. So, often the work as a director was to just keep filming and try a range of direction, until he got to that place, then picking out those moments. He was incredibly talented, and his family were really supportive and passionate about the film. It was really lucky we found him, child actors like that are rare, especially for a low budget short. Credit again to Sue Odell for being an amazing casting director!

How did you find finalising it all in the edit given the amount of footage you shot?

The story was reinvented in the edit. Because we’d filmed a lot of improvised material, it meant there were a lot of options far beyond what was scripted. The ending as it is wasn’t scripted, it came about through experimenting in the edit. For me, the ending makes the film, in no small part thanks to Luke Hester’s ethereal score, Seb Bruen’s meticulous sound design, and Vlad Barin’s moody and rich colour grade.

Is there anything in particular you’re hoping audiences take away from My Brother is a Mermaid?

Hmm, tricky. When making a film I don’t think it’s helpful to think too much about the audience… whatever you do some people will like it and some will think it’s crap. But everyone can sense when you try to anticipate and appease the audience’s reaction, and that’s when things become really sterile and soulless. Instead of thinking about the audience, I think about myself and my close friends and family, and make something that I think we would genuinely connect with. My family and friends were a big part of the test screenings… I got particularly brutal feedback from my mum! Usually if we all genuinely like it, then I’m sure there’s a bunch of other people who will too.

I think one of the nicest things anyone said about the film, was that it had a sort of spiritual dimension to it when most stories about trans people focus on the physical. I really liked that comment, so I hope more people take that away from it. I guess I want people to be immersed in Kuda’s imagination, and feel the mini sense of wonder that he has toward Kai and the world in general. Ultimately, it’s really a simple story about the power of love between siblings, and above all I just want people to feel that.

What are you working on now?

I have a feature version of My Brother is a Mermaid in the works, it’s taking on quite a different shape to the short, which I’m really excited about. I’m also aiming to try my hand at commercials and music videos this year, and aiming to get another short made… covid or no covid! I’m keen to meet new collaborators, so anyone who enjoys Mermaid, feel free to get in touch!