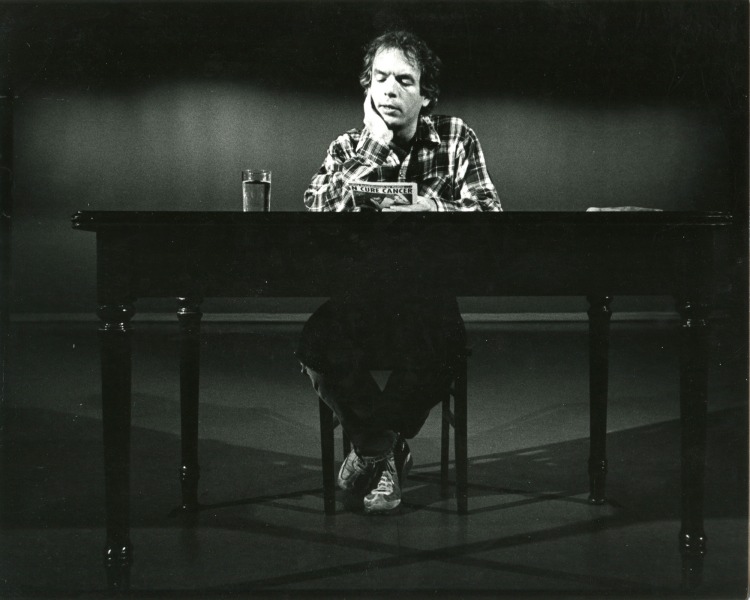

Steven Soderbergh’s body of work has always presented something of a problem for critics, its sheer eclecticism eschewing any easy pigeonholing. Despite this, however, there has always been an identifiable thread – both visual and thematic – running through the films. Yet here, for perhaps the first time, he feels almost entirely absent, a ghostly figure pulling the strings from the shadows. Rather than being a problem, though, this disappearing act may well be one of And Everything Is Going Fine’s best filmmaking coups. For his first documentary, Soderbergh has created a ‘gift’ to the family and fans of the self-described ‘poetic journalist’ Spalding Gray, who died in an assumed suicide in 2004. Very appropriately for a film about someone renowned for their autobiographical monologues, Soderbergh has left all the talking to Gray, assembling archive footage, interviews and photographs into a coherent and captivating document. When asked what he feared most about death, Gray would apparently answer that “I won’t be here to talk about it”. Soderbergh, one feels, has given him the chance.

According to the film’s producer (and Gray’s widow) Kathie Russo, Soderbergh and his editor Susan Littenberg culled the film from over 120 hours of footage, and it is important to recognise the part that Littenberg must have played in making the film what it is. The tight-knit structure created by Soderbergh and Littenberg allows Gray’s words to seemingly form themselves into one last, final monologue, and although And Everything Is Going Fine may be 90 minutes of one person talking about themselves, it is never self-indulgent. As Gray himself puts it: “I’m not a navel-gazer”. He is merely talking about the world as he sees it through his personal experiences.

And the world as Gray sees it is an interesting and humorous place, but one lined with darkness. Soderbergh and Gray first worked together back in 1993, when Soderbergh cast Gray in his early masterpiece King of the Hill, having read his book Impossible Vacation and deciding he was right for the character of Mr Mungo. Perhaps ironically, perhaps disturbingly, Gray was thinking of suicide around this time and accepted the offer of Mr Mungo – a character who kills himself – as a way of exploring these ideas vicariously. Suicide seems to have been something of an inescapable recurring theme for Gray, with his mother dying by her own hand in 1967, his own failed attempt in 2002 and his own untimely death.

Despite this dark undercurrent, Gray’s work was always as funny as it was insightful, and the film stands as a testament to his skill for entertaining and poetic storytelling. Russo has stated that Spalding was an ‘audio guy’ who always felt like something was missing from the film adaptations of his work, but there is nothing that feels missing here – not even Soderbergh.

https://youtu.be/O3qs42Cx0EA