At the start of The Bang Bang Club the South African photojournalist Kevin Carter (as portrayed in the film by actor Taylor Kitsch) is asked what makes a great picture. He hesitates and the film flashes backwards in time, but the moment is returned to later on, and we hear Kevin’s answer: “One that asks a question, not just a spectacle“. It’s a fitting comment, and one that clearly applies to The Bang Bang Club itself. Does that mean it’s a great film? Perhaps not, but it certainly leans in that direction.

At the start of The Bang Bang Club the South African photojournalist Kevin Carter (as portrayed in the film by actor Taylor Kitsch) is asked what makes a great picture. He hesitates and the film flashes backwards in time, but the moment is returned to later on, and we hear Kevin’s answer: “One that asks a question, not just a spectacle“. It’s a fitting comment, and one that clearly applies to The Bang Bang Club itself. Does that mean it’s a great film? Perhaps not, but it certainly leans in that direction.

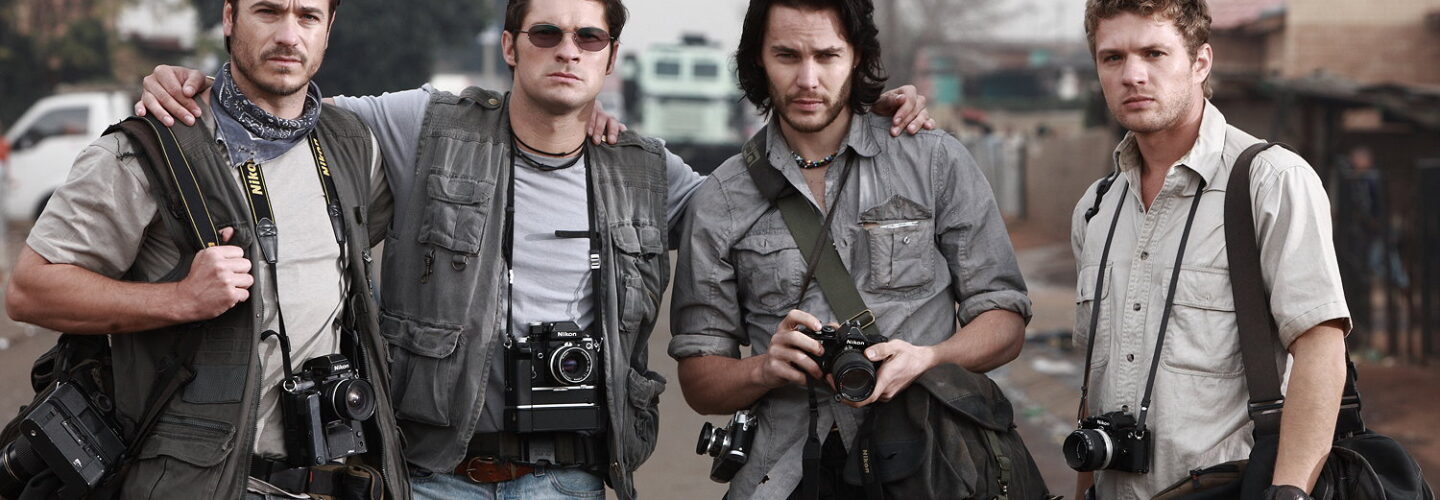

The film tells the gripping true story of the eponymous ‘club‘: a group of photographers operating in South Africa during the Apartheid of the early 1990s. Alongside Carter were Greg Marinovich (Ryan Phillippe), Ken Oosterbroek (Frank Rautenbach) and João Silva (Neels Van Jaarsveld). Both Carter and Marinovich would win Pulitzer Prizes for their work during this period: Carter for an image of a vulture stalking a starving young girl in Sudan, Marinovich for his image of a burning man being struck on the head with a machete. These striking images, and others, are recreated in the film as the story unfolds (there is also an exhibition of the group’s work on display in the Filmhouse until the end of the festival).

Despite being based on a book (The Bang-Bang Club: Snapshots From a Hidden War) written by Marinovich and Silva, the film never glorifies its protagonists, and many of the questions raised by the film come from the inherent ambiguity of character which seems so essential to being a photojournalist of this variety. Although being sold as a film about a group concerned with ‘spreading the truth’, the film itself offers a much richer tapestry of moral uncertainty. For instance, when Marinovich (who takes centre stage in the film) is told that one of his images won’t be used in the paper he works for, he enters a struggle of conscience about why he’s doing what he’s doing – but quickly comes out of it when he’s told the image will be used elsewhere around the world. It’s never made quite clear what it is that brings him out of his inner concerns: the idea that the image will be seen (and therefore the truth spread), or the fact that he’ll get a decent paycheque and a certain degree of world fame.

Inevitably, the film also strays into exploring the question of whether the photographers are right to snap away at their subjects without helping them (during a press conference, Carter is taken to task for not making sure the girl in his Pulitzer-winning photograph received food), and there’s a definite sense of the detachment and harshness required for this line of work. When Marinovich takes his editor (and girlfriend) Robin to photograph a murdered child, she breaks down. There’s nothing he could do to help the family, he later insists, other than photographing the child. Interestingly, though, the photographers don’t hesitate for a second to help their own when one of them is shot.

As this might suggest, the film never shies away from the harsher aspects of the job and the depiction of violence in the film is refreshingly serious. In one scene Marinovich has to wash blood off the back seat of his car – but it’s a long way from Tarantino. Although I enjoy the aestheticisation of violence as practised by Tarantino et al as much as anyone, it’s good to see a film exploring its true consequences. This is by no means to say the film is po-faced, but merely that it paints a vivid picture of the realities of war as faced by photojournalists.

As this might suggest, the film never shies away from the harsher aspects of the job and the depiction of violence in the film is refreshingly serious. In one scene Marinovich has to wash blood off the back seat of his car – but it’s a long way from Tarantino. Although I enjoy the aestheticisation of violence as practised by Tarantino et al as much as anyone, it’s good to see a film exploring its true consequences. This is by no means to say the film is po-faced, but merely that it paints a vivid picture of the realities of war as faced by photojournalists.

Indeed, the film does a good job of portraying the fear, excitement, and dangers of being a war photographer, if never quite going all the way with it. The film covers a lot of ground and perhaps as a result skims over some issues without exploring them in total depth, but the range it covers seems essential to the photojournalist experience it seeks to convey. For instance, in addition to the moral issues already mentioned, the film also explores things from a political viewpoint (Marinovich’s Pulitzer image is accused of being a ‘white man’s photo used for white man’s purposes’) and a psychological viewpoint (Marinovich’s crises of conscience, Carter’s use of drugs to escape from reality, the addiction the photographers have to the war). Thankfully, the film never judges and offers no answers to its questions, allowing the audience to make up their own mind about the characters and their profession.

On a more critical note, the film starts very badly. The interview with Carter which kicks off narrative is cut short in a terribly melodramatic fashion, and the melodrama only gets worse during the next sequence, in which a young boy warns Marinovich that he’ll be killed if he continues following the Zulus he’s trying to photograph. “I’ll tell them what happened to you” the boy hisses. Thankfully, as the film progresses, the melodrama subsides in favour of genuine drama. It’s also probably true that as an artistic work the film rarely rises as high as the questions and story demand. Plus, as solid as the lead performances are, they never fully enthral, and the film is stolen by the actor portraying the father of the murdered child that Marinovich photographs. Despite only having a few minutes of screen time, the monologue he gives (in a single, unbroken close up) remains one of the film’s dramatic high points.

I agree with your reaction to this film as one of “moral uncertainty.” Many critics have come down hard on this film for not landing on one side or the other concerning the morality of photojournalism recording such violence. What seems to get lost is that far from war journalists, these were S.African news journalists, who would ordinarily be covering election coverage and urban crime, etc. They chose instead to focus on something that was happening in the background for most S.Africans at great personal risk. That choice affected national and international awareness, but at great personal cost for the photogs. I agree with you that this film allows its audiences to come to their own conclusions without shoving a message down their throats. A plus for me.

I do have to disagree with your edict of melodrama. I thought the opening was very effective. And the scene with those two boys in the beginning is one of my favorite moments. But it’s a minor point, surely.

This really low budget film is really a little gem. The art and craft of film making it displays is outstanding. The large street scenes were so real, so very well done. But it’s also full of small perfectly constructed, emotional moments. It captures the sweat, the grit, the raging emotion and the blood of what these moments must have been like at the time, all the time juxtapositioning the absolute focus and calm of the four photographers.

A very interesting, well done film, one that S.Africans should be proud to call their own.