Winner of BAFTA’s 2013 British Academy Scotland Awards for Animation, Gavin C Robinson’s Edinburgh College of Art graduation film Hart’s Desire weaves the charming tale of how an aspiring hermit and an aspiring socialite come together over a shared flask of tea and discover their place in the world. Robinson tells DN how he channelled his own uncertainties about the ideal life into his narrative and the challenges of developing an animation process which would allow him to maximise his time as a solo animator.

Hart’s Desire is my degree film, made in my final year at Edinburgh College of Art. There is a freedom that exists in the animation course at ECA that encourages you to create the film that you want to, regardless of technique or content. The tutors don’t make you fall in line with their personal preferences or expertise. With this in mind I was aware that I wanted to create a film that had something about me at its core. If nothing else, this meant that I had a strong personal interest in the film, which I felt would be important given that its creation would be consuming a full academic year. In fact, for some time before my final year, I had some rough ideas about the kind of film that I wanted to create.

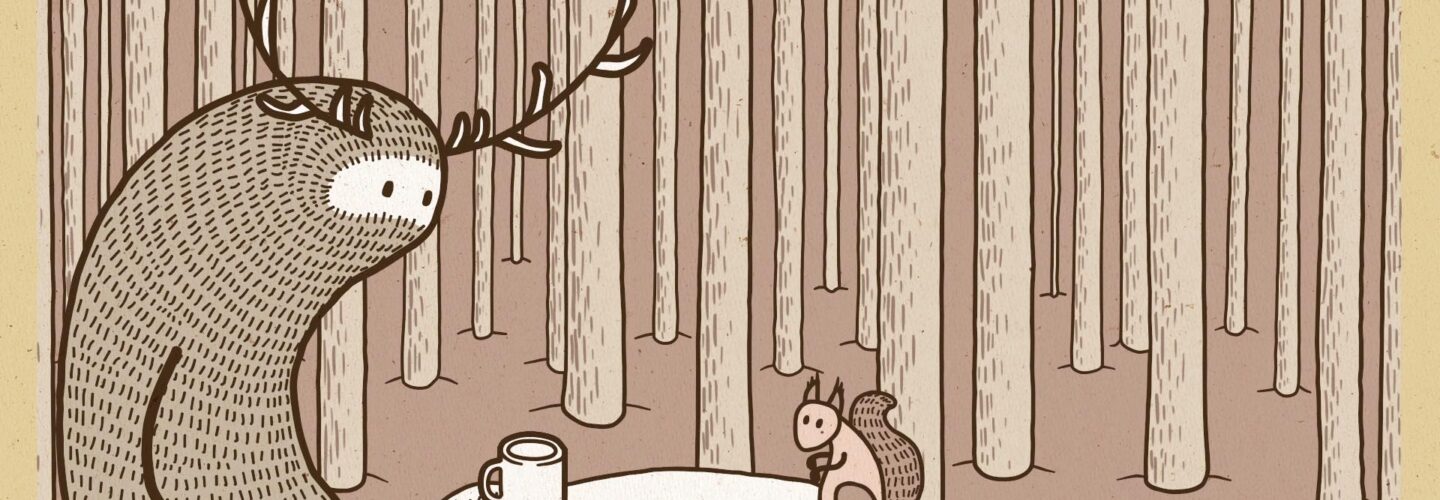

I love the Scottish highlands and the great outdoors generally and, having been born and raised in rural Aberdeenshire with frequent family trips to the Cairngorms, I had the notion that my film would be set in the isolated beauty of a hilly environment. I also have an interest in Celtic myth and folk tales and so was keen that there be a fantastical element. This is where the deer-man character came in, inspired by pagan antlered gods, Herne the Hunter and Cernunnos, but also a nod to the real life red deer synonymous with highland landscapes. While these things were catalysts for the development of the film, I wasn’t out to create something too ‘stuffy’ that would force tartan-haggis-fairies down your throat! I didn’t want it to be overly Scottish or folky but rather more simple and somehow more modern feeling. For help with that and from an aesthetic point of view I turned to my growing love of comic artists like Jon McNaught and Tom Gauld… or basically anything published by Nobrow!

I wasn’t out to create something too ‘stuffy’ that would force tartan-haggis-fairies down your throat!

Having identified the general mood and setting that I wanted, I started developing the story. I had previously done very little in the way of writing and story-craft so one of the first things that I wanted to ensure was that my story would ‘work’. I felt that I needed a simple structure to follow that would form the foundations of a story that I could build upon, while remaining confident enough that (with this simple structure) the narrative would function properly. To do this I worked up a sort of bare bones comic strip and diagrams of the key moments that needed to occur. It helped me visualise the whole thing by having it laid out in front of me, in simple terms on a single page. The natural course of action from there seemed to be to elaborate on my ‘key moments comic strip’ by creating a fully realised comic of Hart’s Desire to serve as my storyboard.

I wanted to approach the comic as a project in itself, forgetting that these images would be animated, and make a functional and pleasing piece of narrative art in its own right. My hope was that this process might help me to develop a more considered approach to the composition of shots and eventual edit of the film: something that may have been lacking if I had simply created a storyboard for animation. Clearly, the most obvious remnant of the comic in the final film is the use of simultaneous panels splitting up the action. I was quite excited by the idea that this would liberate the way I could tell the story from the confines of a 16:9 window. I think that the comic also helped because if I had been working on a more conventional film storyboard, the practicalities of animating what I was drawing would have been on my mind and may have, too strongly, informed the decisions that I made. It’s a lesson I learned while studying architecture: we were strongly encouraged to develop designs with pencil and paper rather than going direct to CAD software where the lines we drew and marks made would almost certainly be confined to our own perceived limitations or abilities with that software. If you develop your work with more freedom, on paper, you’ll usually find some way of clearing the technical hurdles when you come to them, while retaining your original creative vision.

I wanted to make this film, as far as possible, by myself.

I think I’m a bit of an introvert. It’s another part of who I am that finds its way into the film’s themes of solitary vs social existence but it also meant that I wanted to make this film, as far as possible, by myself. With the time constraints of the university course I was aware that animating a film of around 6 minutes single handedly might be a fairly big ask, particularly since I was hoping to achieve a hand drawn, crafted aesthetic that would complement the natural setting of the film. The first few months were spent on research and development so, when I came to finally start animating, I felt that I had to find a way of making it a relatively quick process (in animation terms at least). What I settled on after a few tests was an entirely digital workflow that included hand drawing in Photoshop, character rigs created and animated with Anime Studio, and some simple compositing in After Effects. The whole film was created with my trusty MacBook and graphics tablet. Animating most of it with Anime Studio ‘puppets’ really made the whole thing achievable for me at the time, and I feel that I was still able to create something of the hand crafted look that I had hoped for with a combination of a ‘noisy lines’ setting on Anime Studio and more traditional hand drawn, frame by frame, mark making (the old man’s beard hair and most of the backgrounds for example) as well as by sampling paper textures throughout.

I did have to give up on my one-man-mission when it came to the audio for the film (and I am of course very glad I did!). Will Anderson put me onto sound designer Keith Duncan, who had worked with him on The Making of Longbird. I really wanted the sound design to be understated and I kept using the word ‘delicate’ when talking to Keith. He’s a really enthusiastic guy and basically the day after I had talked to him about the project he had run off to the woods to record twigs snapping and such, which he used and augmented to compliment the movements of the Deer-man, for example. I met the composer, Mike Vass, when he approached me about a separate project. As soon as I’d heard his music I knew that it would fit really well with what I wanted to achieve. Like my hopes for the film, Mike’s compositions certainly have their Scottish roots, but are entirely un-stuffy: they’re innovative and modern. In fact, Mike’s latest album has recently been longlisted for the Scottish Album of the Year Award, alongside an amazing list of artists. Mike was kind enough to compose and perform original music for Hart’s Desire, meaning that he could pick up on specific things within the film. I really couldn’t have been happier with it.

I fully expect never to be able to look back at a film that I’ve made and be entirely satisfied with it.

I’m pretty pleased with Hart’s Desire generally. There are definitely things that I would change about it, things that I would do differently now that I have some more experience as an animator. That’s the nature of progression I suppose. I fully expect never to be able to look back at a film that I’ve made and be entirely satisfied with it. But that’s an oft-expressed sentiment isn’t it? And it’s the way it should be. Onto the next thing (of which I hope there will be many)!