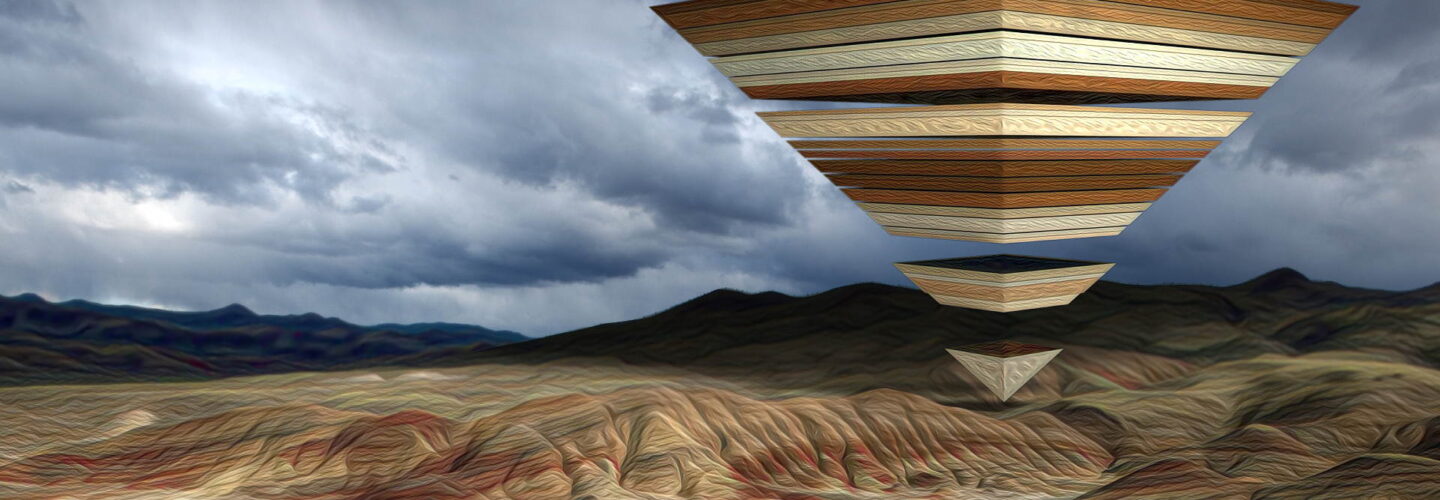

Through the years Kurtis Hough has taken DN on many wondrous trips of discovery as he explores, documents and transforms the natural world into captivating art pieces with vibrant soundtracks. Bringing his geology trilogy to a close is new film Painted Hills – A sculptural and painterly look at the geometry of geology. Kurt takes us through his image manipulation experiments and finally reveals just what he gets up to out there all alone in nature.

Painted Hills’ opening shot immediately raises questions about what it is we’re looking at. Were those initial 20 seconds you telling the audience to recalibrate their expectations for what they’re about to see?

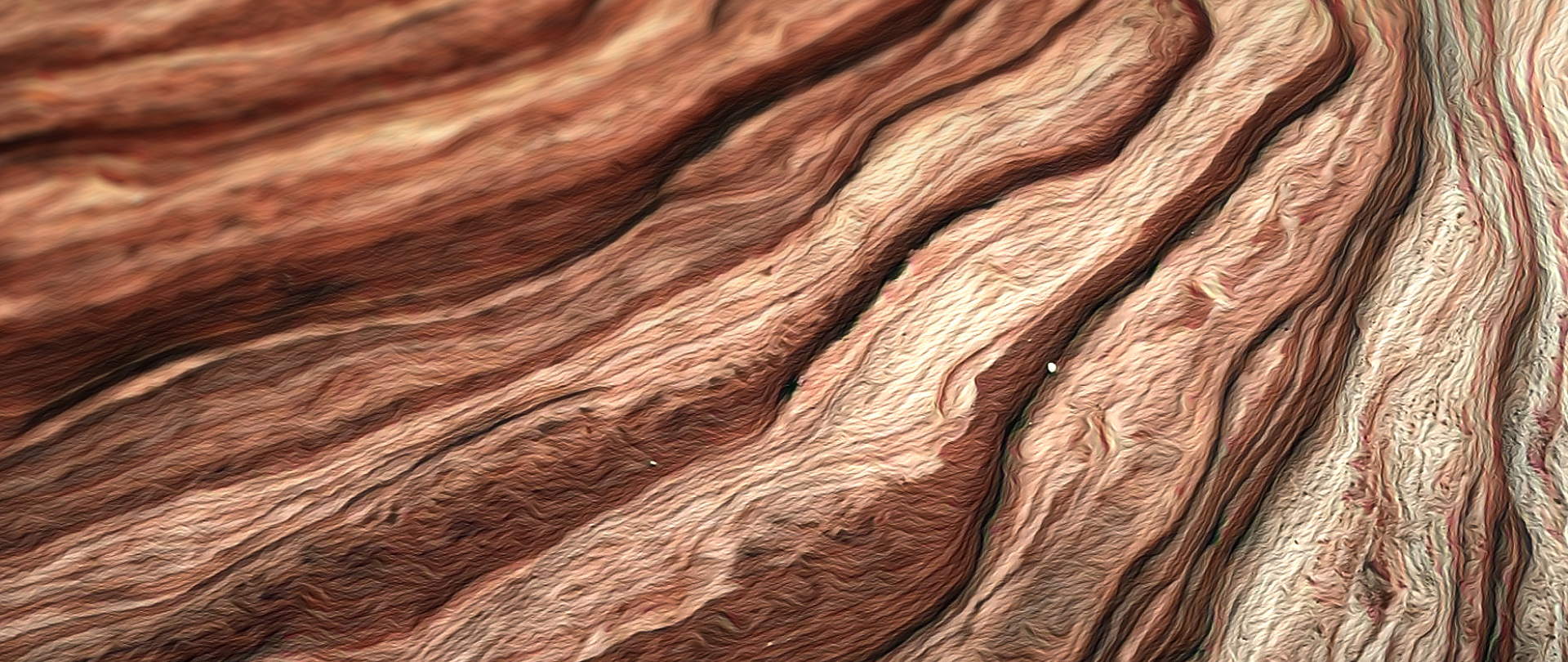

I often like to start close up to a landscape, to where you don’t know what you are looking at. Starting with abstraction and slowly revealing the world as it progresses is something I find interesting. Cryosphere is similar in that way. That opening shot actually used to be longer, about 35 seconds, but I found by breaking it with the introduction of the plants, helped the rhythm of the shots better.

As you’ve done numerous times before you headed out into the ‘middle of nowhere’ for this to shoot. What’s the essential kit you take with you and how do you spend your time once you’re out there?

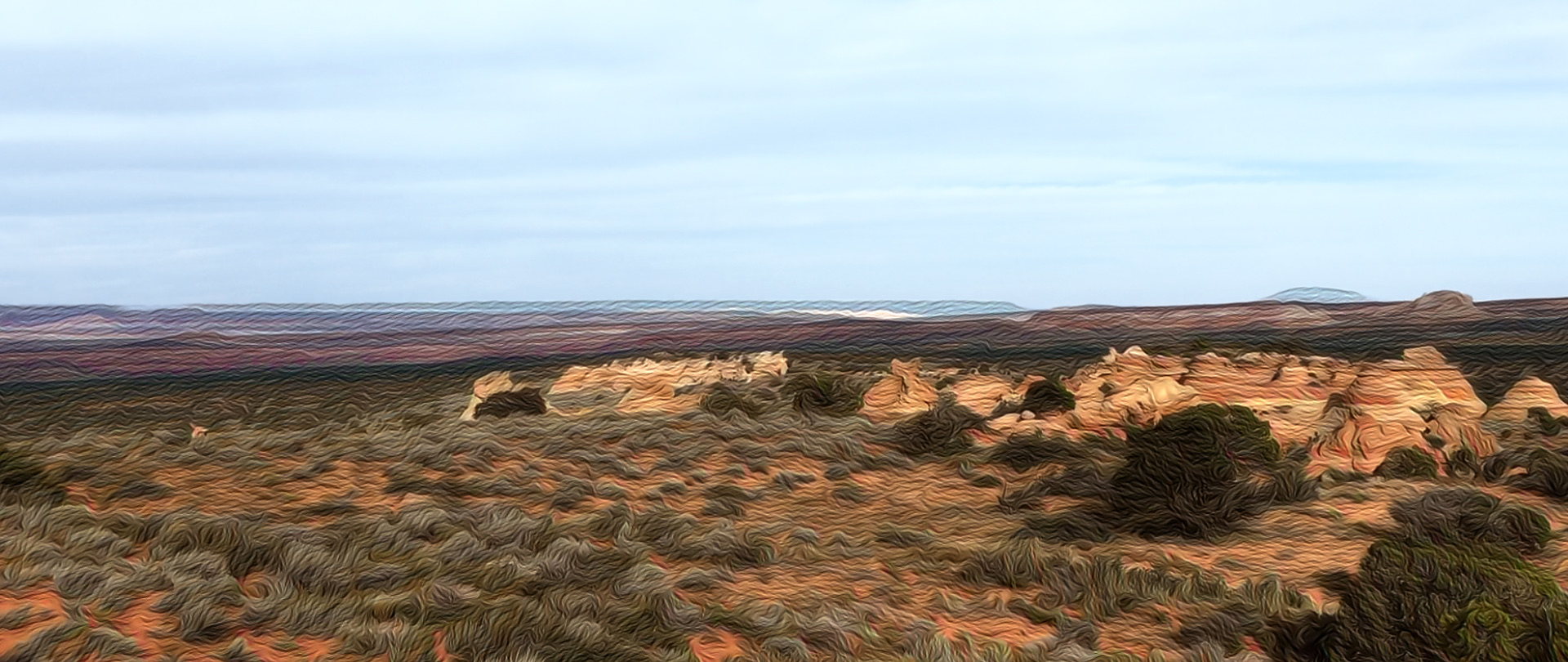

Part of these projects is to learn for myself about these landscapes and see what inspiration comes from exploring them. For this I ended up camping by myself on the border of Utah and Arizona in the Coyote Buttes wilderness. Only 20 people a day are permitted to explore this area which is ripe with sandstone hills and banding colors. There were no trails and was as close to an untouched landscape as I’ve explored. The day I got a permit, I backpacked my tent, cameras, and food to the entrance. At dawn I headed out, with two Canon 5D cameras, tripods, intervelometers, and lenses. This was the first time I used two cameras at once which really helped, considering I only had one day to shoot, and it allowed me to capture different angles of rock with the same light conditions.

I spent the day hiking north and photographing along the way. Then at dusk I came across the most magical peach rock formations with pools of shimmering water and endless views of banding color (shown in the final scene of the film). I realized I still had to navigate my way back to camp and the light was falling, but I couldn’t leave this spot without capturing it in camera. Once it became too dark to photograph, I began heading south. But since there was no trail it became difficult to find landmarks along the way. As I’m quickly trekking through hill after hill of sage brush and sand, a sharp rattling noise came out from near me. Now the exhilaration of filming that magical sunset was gone, and a new more sinister part of this wilderness was presenting itself. I took out my tripod and used its legs to swipe the ground in front of me which did the trick and I didn’t have any more encounters with rattlesnakes. Thankfully my phone, which I had also been using to film during the day, still had some battery life and was able to navigate me toward my tent in the dark. It was a long 14 hours of hiking and filming by myself, but was fully worth it to produce this project. Part of these projects are about learning and this one taught me a lot.

Part of these projects are about learning and this one taught me a lot.

The film’s transformed landscapes were the result of your experiments with Google’s Deep Dream algorithm. As the software hadn’t previously been used in this way how did you know, not only that it would be possible, but when you’d arrived at the final look?

The concept was to look at the shapes and colors of arid geologic landscapes through the lens of a painting. Deep Dream was released in July of 2015, while I was already a year into planning Painted Hills. But once I started experimenting with it, I realized the concepts I wanted to explore with this film fit perfectly with the painterly look I could achieve with Deep Dream. I like to work organically and redesign as I’m physically working on it, so I decided to jump in and change my concept to fit with this new technology. My friend Curtis Randolph, who is also an animator, and knows far more about coding then me, helped me load the Deep Dream to my home machine and customize a batch sequence output, so I could run my image sequences through the code, shot by shot. Most everything I had seen created from Deep Dream were still images, and “dog slug” video clips with furry eyeballs, which quickly felt like an overused novelty. I saw an opportunity to refine its use in a more deliberate way, and show its possibilities through the filter of my dreamworlds. The result connected my oil paintings with the timelapse video and surreal animations I have been developing for years.

With the processed images in hand, what additional stages did the footage go through?

After running the shots through Deep Dream, I spent a lot of time blending its use over the original footage, and fading it away by the end. Then I began adjusting certain scenes in After Effects and adding 3D elements which have roots in mathematic formulas found in nature and geometric objects, like the Golden Ratio and Pi.

You recently presented a collection of your films at the Portland Art Museum – did re-experiencing the last 10 years of your work reveal any new insights into your journey as an artist?

That was a great experience to show a retrospective body of work on the big screen with an audience. I’m always interested in the connections of an artist’s work and seeing their progression. Since I normally screen in film festivals, each short is being shown by themselves in a block with a wild variety of other filmmaking styles. It’s hard to pick up on each filmmaker’s style or point of view when given such a short sample size and timeframe. I feel the same way in art museums. When I look at a Rothko painting in a room of a bunch of different paintings, it’s not as interesting as an entire room of his work where you can see the differences and similarities that connect it all together, which makes it far more interesting and powerful.

With your geology trilogy of Cryosphere, To See More Light, and Painted Hills now complete which other aspects of nature do you have your sights set on?

I’ve been thinking about water for a long time, and plan to someday explore that as the subject. What is next is hard to say, but I like the direction I’ve been going in and hope to continue producing new pictures.