Advertisements which attempt to play on your emotions (or pray on them) are a dime a dozen but as all good filmmaker know, creating a piece of work which strikes a genuine emotional connection with its audience is a much harder, yet infinitely more rewarding task. Judging from the number of tears shed in the comments for Jono Seneff’s Tesla Model 3 spec commercial it would seem that the LA director’s Feel It spot sits firmly in that latter category. After wiping our eyes DN asked Jono to share how a dream, hearing loss and the frustration of an unrealised opportunity spurred him into action.

The images for the Tesla spot were actually handed to me by my subconscious. I had a dream about a deaf man in the desert playing an electric organ attached to a huge array of speakers. I always thought it was a cool image, so when I decided I wanted to do a car spec, I thought about how I could use it. So I basically reverse engineered a story to fit that final image. At the same time, the story is personal because I grew up in a very musical home and I lost hearing in my right ear for a month in college. I found myself in one of those soundproof rooms with an ear doctor playing different frequencies into special headphones and me just shaking my head like the character does as he losing his hearing in the spec.

So I wrote the script, got positive feedback from friends about it and then promptly did absolutely nothing with it. Months later, I found myself attending a panel about independent film distribution where a young director mentioned how he had made a car spec that had gotten him representation and loads of other opportunities. I actually didn’t hear the rest of the story because I got up and walked out. I was so frustrated that I hadn’t made my own yet that I couldn’t take hearing about this director’s success. Probably not a healthy attitude to have but it got me moving. That very night, I decided to actually make the project happen. I knocked on a few doors and made a few calls. Six weeks later, we were in the middle of a lake bed shooting our own car commercial.

The images for the Tesla spot were actually handed to me by my subconscious.

In terms of finding my crew, it helps that I am in my last few months at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts MFA program. The best thing about film school — by far — is the people you become friends with. In fact, my DP Bash Achkar was the first person I met there. About 75 percent of the crew ended up coming from USC. Our crew size oscillated from just me and an actor, up to 20 people on some days. Our schedule was a little crazy as well. We shot scenes whenever we could find the time or a location was available. So the production phase itself lasted many months.

We shot on the Red Dragon in 6K Full Frame Raw with a single lens, the 21 mm Zeiss CP.3. I would have loved to have shot on a lens with a little more character but we simply couldn’t afford to rent those. We also had VFX elements that would become much more difficult if we were to have shot in anamorphic.

Casting was probably the most complicated part of the process. We had to cast five versions (60s, 70s, 80s, 90s and present day) of the father character and three versions of the daughter character. Age-induced actor swapping almost never works for me in feature films, so I’ll admit that am not sure why I decided to write something that required it…

My first roommate in Los Angeles, Arvin Lee, is an amazing actor and also happens to know all the technical ins and outs of breakdown services and the casting process at large so I put him in charge of casting and we did all the auditions together. We used CAZT, which is a free casting space in LA, and we saw hundreds of people for the different roles.

We did multiple chemistry tests with the father and the daughter characters where we had the different actors improvise an early morning driving scene together. Once we had a locked present-day version of the characters, we could start going back in time and figuring out who of the many people who submitted headshots could pass as younger versions of them. This process was very time consuming and research-heavy.

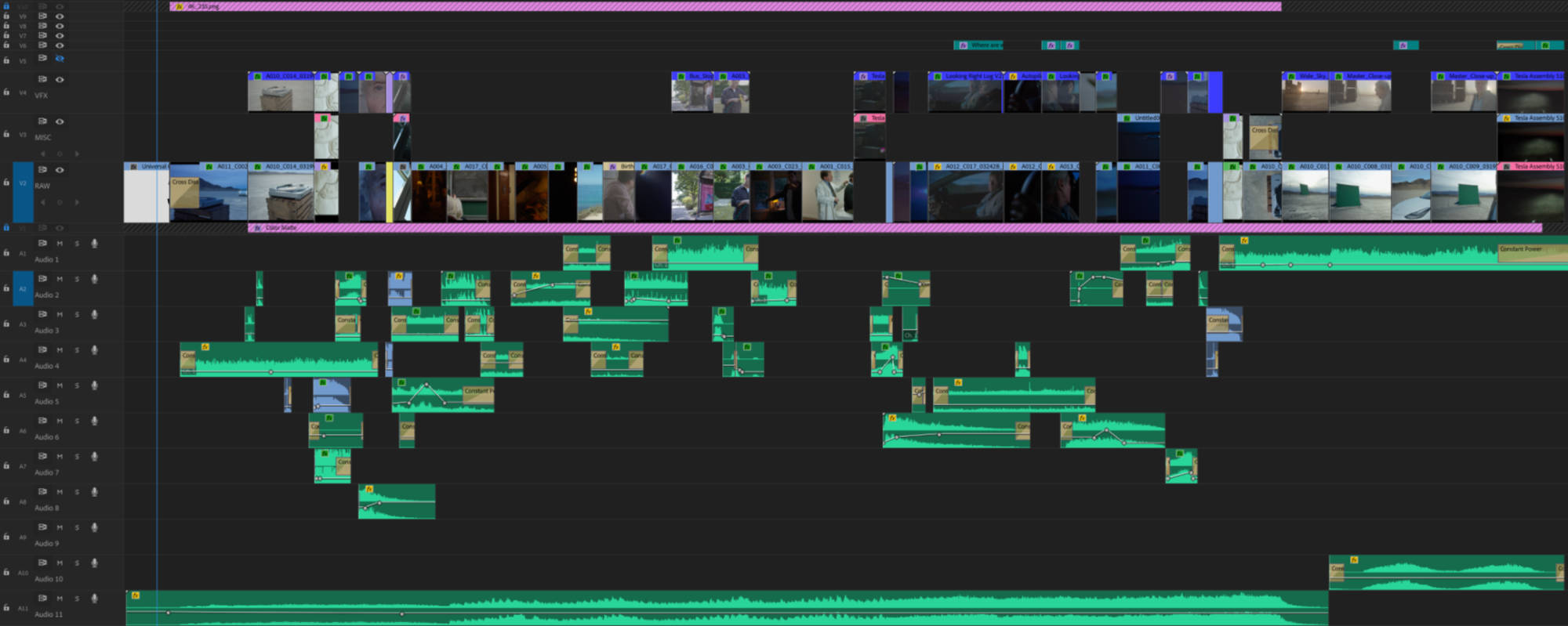

I edited the project myself in Premiere on the iMac Pro whenever I had free time to work on it. I previewed in 1/4 resolution (mainly because my drives weren’t fast enough for higher res previews) and everything went smoothly. As we approached the end, I had no objective sense of what I was looking at, so I brought in close friends who I had kept away from the early edits in order to get their fresh takes on it. I highly recommend doing this. Don’t waste your friend’s objectivity by showing them cuts too early.

Although we shot in 6K, we finished in 4K with an aspect ratio that changes from scope to 16×9 for the final scene of the commercial. That was actually a last minute decision in the edit. We had framed everything for scope, but since we shot everything in full frame, I was able to open it up at the end, which I think helps sell the emotional transition.

Don’t waste your friend’s objectivity by showing them cuts too early.

There were a few things in the script I knew would be challenging to pull off visually. For those elements we couldn’t afford to do practically, I turned to Stephen Burchell for VFX on the project. He did a lot of small things like replacing the poster at the bus stop, as well as changing out what was on the Model 3 screen. The biggest thing he did, however, was the speaker array in the desert. Those shots were much more complicated, as they involved developing the actual look of the speakers, a moving camera track, and integration of moving 3D assets and shadows. I bought a number of 3D models while they were on sale at Turbosquid and then Stephen brought them into Blender 3D. He then used After Effects to composite the final shots.

This project was the first time I didn’t do my own coloring. I reached out to Bryan Smaller on Instagram who works as a colorist at Company 3. A few hours in their Santa Monica offices and we were done!

For sound design, I knew I needed a team that would be able to interpret the script in a non-literal and engaging way. I had seen Defacto’s stuff online and just reached out to them. We worked remotely via Frame IO and I am really pleased with what they brought to the project. Every time they sent over a pass, it was like getting to watch the cut for the first time.

The composer on the project was Andrew Gerlicher. Andrew and I have been working on films together since our freshmen year of college back in 2010. I edited with temp music, but anytime I sent a cut to Andrew, I made sure to mute the temp in those exports that way he wasn’t just trying to emulate whatever track I was using for rhythm. Andrew came up with many different cues for the music that he would email over to me. Then, whenever I had the time, I would go over to his studio, sit in the back and talk story. Every time I didn’t like the way something was working, I tried to direct Andrew exactly the way I would an actor. I would reiterate the context of the scene and try to reinforce the goals and objectives of each section with the use of verbs.

Although Andrew is incredibly talented at utilizing his sample libraries, we knew we didn’t want to rely on samples for the strings, as they are notoriously difficult to fake. So once we finished the composition, Andrew arranged the music for strings and we sent the score off to the Budapest Scoring Orchestra in Hungary. The BSO is an amazing resource for smaller films that want to have real musicians bring their expertise to your film. They allow you to book orchestras for very short amounts of time, which makes it much more cost-effective than anything else we could find. We only paid for a 30-minute session and they recorded it all on the third or fourth take.