It’s a cruel irony that childhood is a time in which we expectantly look to the supposed freedom of our future adulthood only to miss the carefree existence of our nascent years upon arrival. In poetic experimental short The Lollipop Girls Struggle on the Hard Earth, Austin Artist and Filmmaker Denise Prince indulges in the fantasy of a return to childhood, only for it to be disrupted by the force of desire. With a body of work which spans mediums, techniques and artistic realms, it was our pleasure to engage Denise in a wide-ranging conversation about her larger artistic expression, as well as the specifics of life’s pretends expressed by the lollipop girls.

A heads up, there are several NSFW images in the trailer below and throughout this interview.

How do your concepts tend to filter into the various artistic expressions you’re active in as a multidisciplinary artist?

My central interest as an artist is in indicating signifiers, the structures of interpretation we use to decode or interpret meaning in a work and in life generally. I am almost exclusively trying to make explicit Fantasy and the Real in all my work, whether subtly or not. The casual observer might notice they are making sense of a piece; one series of my photography was once described as opening a book on a random page. You can tell there is a narrative but you sense you must fill in the gaps. In that work, I’d imply narrative but interrupt or complicate it. The viewer won’t always know that this is what interests me most about the work though. They might simply process a version of what the image means and feel satisfied.

I’m fascinated with the fact that we constantly make meaning and mostly don’t notice that we are because it seems natural. The best example I can use to illustrate is Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Philosophy says that we take reality for shadows on the wall that do not represent reality. And psychoanalysis shows us how we make meaning. Both are accurate and lie behind what fascinates me about life. Occasionally, I just make a beautiful object, but usually, no matter what medium I’m using or what the outside appearance is, I’m pointing to life’s pretends and how we read ourselves and others as objects, play with meaning and are sometimes more buoyant because of it.

I’m fascinated with the fact that we constantly make meaning and mostly don’t notice that we are because it seems natural.

What set you on the path of The Lollipop Girls Struggle on the Hard Earth and how did the project develop from there?

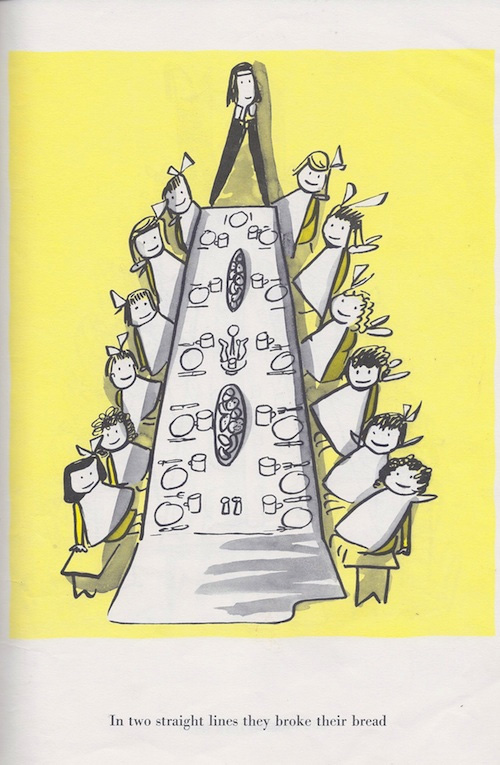

The Lollipop Girls Struggle on the Hard Earth began as the concept for an art event. Although I did not grow up close to the storybook Madeline, imagining a room with twelve twin beds is a rich fantasy space for me. I presumed many women would share the longing for a return to simplicity and the splendor childhood can represent. Much of my work makes explicit what is real and what is fantasy. So, I knew that a return to childhood required bringing the potency of being an adult along.

This is why the women in the film wear only the red tights in bed and other activities that particularly exemplify desires that bridge childhood and adulthood. Children imagine being an adult with as much fantasy as adults remember childhood. So, I see personal longing and the times when it is temporarily satisfied like effective advertising. I enjoy the beauty of the pretends.

Having worked in photography, staging images that usually started with a fantastic location and imagining different possibilities for who belonged in there, I also imagined grannies inhabiting the beds.

After filming the bedroom, dining table and badminton scenes, (along with a music room scene that does not appear in the film because it felt too cold and bare) I came across the Futuro House that appears in the film and the “Chelsea Girls” out front smoking. I knew that taking the adult Madeline character out into the world was important. A woman would not be satisfied with a perfected childhood return. Eventually, she takes on the fantasy of the youth who longs for the adult world. And so, my character embodies the pursuit of her desire until she looks up and her life is fleeting/past.

Was there a specific source of inspiration behind the film’s evocative title?

Classic childhood literature, in part. But first, literally, it was the title I gave a photograph I took of two actresses who particularly embodied the girlishness I wanted the film to include who I styled in large, round wigs walking barefoot in a maize field. The script included two scenes of them (I quickly nicknamed them the Lollipop Girls.) running towards camera. Since they were barefoot, walking back to their starting points for each take was painful. I was moved at the way they walked slowly with their arms up as if that would make it hurt less. It reminded me of the barefoot summers of childhood so we filmed and I photographed them walking this way as well as what we had planned.

So much of the film is wrapped up in the fantasies of childhood and adulthood and being a tender-footed youth walking on hot pavement was memorable (I’m from Texas). It is a difficulty that evokes the general state of childhood. Once we take on adult problems, memories of walking on uncomfortable ground are likely to evoke longing or sentimentality, not suffering. I used this qualitative difficulty to describe the central theme because I am trying to talk about Desire (the memory of the missing thing) in the film. The adult longing for something they sense was left behind in childhood. The child (who still cannot distinguish fantasy from the real) pretending to be grown up.

Most people won’t notice this but my film is as much a warning as an indulgence.

Classic childhood literature is referenced throughout the film and the title seemed somewhat like the singsong of a story oriented to a child while also being somewhat facetious. Making sense of life and getting used to an awareness of mortality is daunting but also by far a privilege of people for whom fantasy too often is taken as real. So, I’m saying it is in some ways a nod to the fairy tales that were sometimes grim reminders of life lessons, moral tales. Most people won’t notice this but my film is as much a warning as an indulgence. I meant to talk about the tragedies of growing up and having the pretends of childhood torn away from you. It is necessary but I’m also suggesting this is an important violence. We must see beyond the fantasies we cherish.

What qualities were you looking for in your multi-generational cast and to what extent did you make them aware of the larger themes of the film?

For the women in their twenties, I was looking for different versions of one person originally. Pale and similar height, tattoos that could be hidden if at all. I was looking for women who knew of the Madeline storybook and shared my imagination that a return to the scenarios of living among a group of friends would be appealing. I assumed that twenty year olds were still getting used to what it means to be an adult. They are close enough to childhood to enjoy the fantasies it promised and still learning how to make their way without those fantasies holding up.

When an actress was able to play and especially had a quality that was girlish I used those shots and added scenes that featured them. Maddy has the most wonderful teeth, imperfect in a perfect way so her toothy laugh was treasured. It felt strange to be working with less racial diversity after so many years of including all types of women in my work. So, I got to work with some wonderful older women I know or approached in grocery stores for the closing scene. I definitely let them know that the interpretation of the center panel of Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (as paradise lost and perfect liberty) was behind the pleasure I hoped to capture on film.

What was the production process like and what did you shoot on?

We used an Arriflex SR3 Super 16mm camera and shot over about 8 months. The first scenes on three filming days followed by a several months wait in which I rethought the narrative and could assemble everyone needed into the final filming days. I styled and fabricated props (cakes, corsages, the bear costume, etc.) myself. We worked with a skeleton crew: cinematographer, gaffer, three assistants, actors and myself as director. I had additional assistants on the out of town scene including a close friend who styled my son (the one male actor) for the enriched / morning scene. The costume change was meant to indicate the way we become more saturated, complex individuals after we become lovers / find love.

Did the film undergo any significant structural changes during the edit?

Originally, the piece was more experimental/esoteric and as I added scenes there was a point at which I had enough narrative established that I needed to resolve the story. The sensibilities I began with – for the piece to work somewhat more like a poem than a story benefitted from editing. Allowing the footage to be rearranged helped structure the amount of narrative I felt the footage could sustain. For many, it may not imply enough of a story for comfort, but my experience of life is one in which life is not like a storybook. Loose ends are not tied into bows. They may seem so in moments, but like the film, balance is buoyant, never fixed.

My experience of life is one in which life is not like a storybook. Loose ends are not tied into bows.

Could you tell us how the theme of a return to childhood only to become restless for maturity fits within the larger Object Lessons exhibition of which this film is part?

Here is a portion of writing a clinical philosopher and psychoanalyst wrote about the exhibition:

“As children desperate to know about the hidden world ahead, we accept both the conflict and the confidence offered to us if only we become an object assigned a value within another’s desire: then the lesson can begin.”

I start with that because the film is about Desire and the lesson never ends. Again, Desire as the memory of the missing thing or as you put it, “restlessness”. We are driven in life by desire and this is valuable. We just often spend a lifetime learning its finer lessons, like knowing the difference in what we think we want and what we actually want, what is real and what is fantasy and that sort of thing.

The exhibition Object Lessons centered around the transition from childhood into adulthood and the difference in fantasy from both positions. The perception of life shifts so fundamentally at puberty that it encapsulates or can stand in for much of the fantasies that we contend with later in life as well. That restlessness/fantasy organizes our experience with everyday reality and tells us who we are. These concerns describe to me what it is like to live, these describe my experience. Which I hope translates into the human experience. The way an adult mind and an identity is composed, comprised, compromised. We are pieces patched together that we resist and accept and negotiate with. This is where I am many years after my Object Lessons began.

What new projects do you have in the works at the moment?

Possibly a large scale installation. A location that would serve as context to play out many fantasies in film and performance, etc. A lot of my work begins with a location that is saturated in style or meaning. I might create one to work from within. I’m also working on a fashion based street art campaign and still making the photo based work used on the posters. This work is highly relevant to the film but from the opposing direction. It makes explicit what is real. This work is on my website under portfolio three. This work will show in New York, Toronto, Chicago, Houston and Austin in 2019. I’m trying to find street art posteriors in Paris.