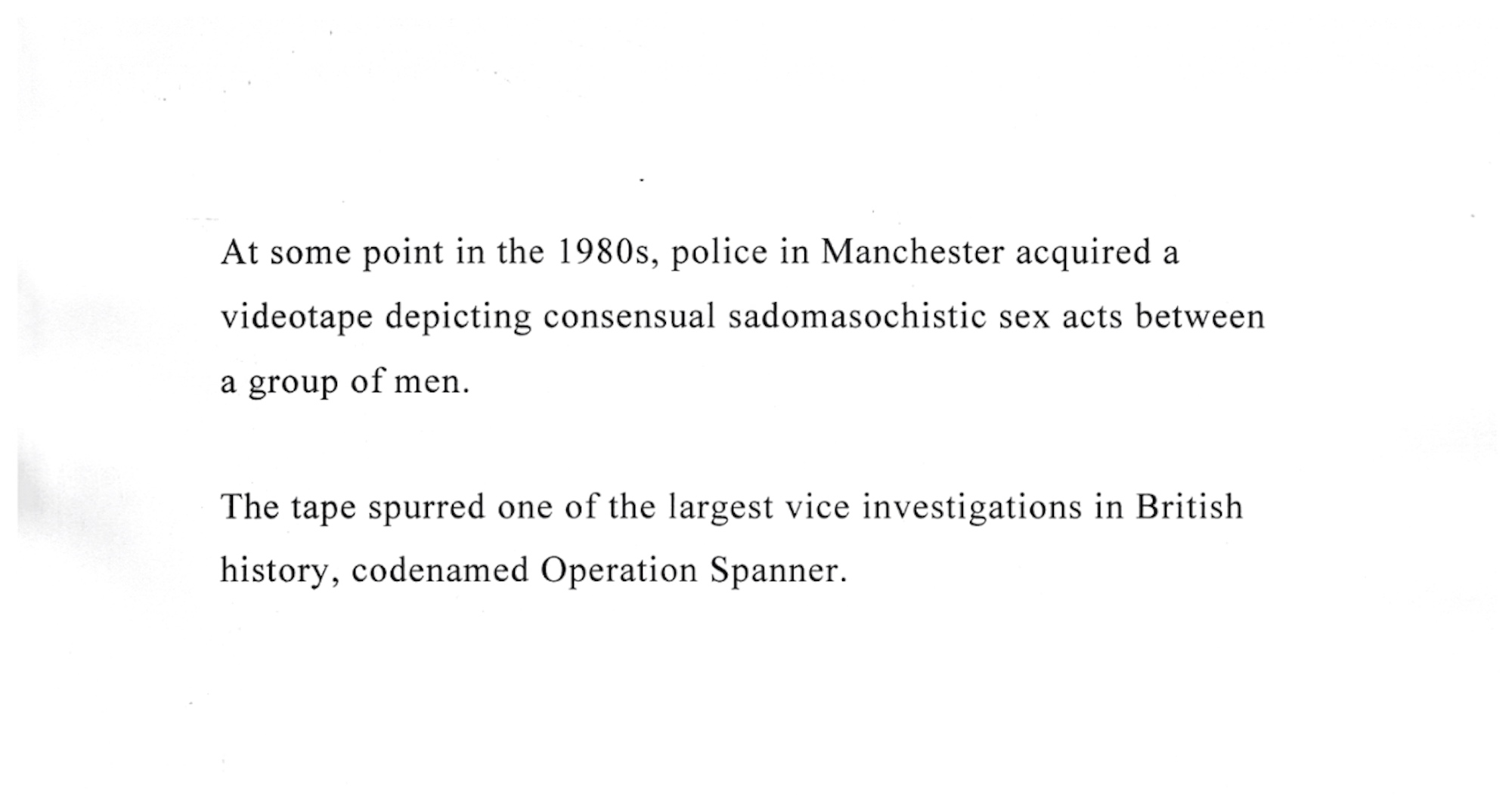

Prolific documentary filmmaker Charlie Lyne (last seen on DN here) is at BFI Flare this year with a short documentary based on Operation Spanner, a police case where 16 men were convicted of crimes of filmed consensual sadomasochistic behaviour. The case marked an important moment in LGBT history as the men were convicted of a supposed crime they were fully consensual to. DN caught up with Charlie ahead of Lasting Marks’ presentation at the festival to talk about the inception and creative process behind his history-changing documentary.

Start from the beginning, how did you hear about the trial and Operation Spanner?

I can’t remember exactly how I landed on it, but I remember first hearing about it at least 10 years ago when I was a teenager and I think it’s because I’m interested in film censorship and obscenity, and the changing concept of obscenity throughout history. When you read about film censorship and obscenity, Operation Spanner comes up a lot. It wasn’t a pornography case but the fact that these men were identified because of the home videos they’d made meant that it fell under the remit of obscene publications squad which dealt with pornography and horror movies. So, I stumbled upon the Wikipedia entry for Operation Spanner and was intoxicated by it for a lot of the reasons other people are which is the seeming absurdity of it. The idea that these men could be prosecuted for assaulting one another consensually in a sexual context. Now, looking back at it, I realise how simplified that account of the case that’s on Wikipedia is. The film grew out of a desire to complicate the history of that case and explain it a little better and do better than just echoing the police line.

To grapple with it more and flesh out the shallow nature of the narrative?

Yeah, for instance, one of the very prevailing themes in any article on the account of Spanner is that the police began this investigation because they saw these tapes, and either they were so extreme or the police were so naive that they mistook them for snuff films or documents of extreme torture or murder. The story then goes that they investigated these things and found that the men were all alive. So, at worse, it presents the police as bumblingly naive, and in actual fact, if you look over the history of the case there’s not a lot of evidence to ever suggest they thought these tapes were anything other than documents of consensual sadomasochistic sex. But because that line was repeated often enough and it’s such a simple, appealing story, it remained a popular part of the Spanner story. Hopefully, the film paints a slightly less one-sided portrait of the reality of that case.

I think it does. I like the fact that you don’t have a name at the start that introduces him and instead you leave that until the credits. Was that an intentional creative choice or was it the case that he was the only one willing to speak with you?

Yeah, it was quite hard off the bat to find anyone. Of the 16 men, the vast majority immediately put it behind them and did no interviews about the case and didn’t want any part in the activism at all, with the exception of three men who appealed the case all the way to the European Court, where again they lost. Of those three, sadly two have since died and the third is Roland, the man who appears in my film.

Hopefully the film paints a slightly less one-sided portrait of the reality of that case.

The form of the film with his voice and then this montage of paperwork had been in my head from the beginning and that’s how I saw it. Part of what appealed about that was that it universalised the voice and that Roland stood in for all of the men. That’s not to say they’re all the same or that Roland doesn’t have his own unique experiences. But, for all of the men, it was a very traumatising and uprooting experience in a myriad of ways. But there were also these really universal aspects to these stories, where they almost all suffered some kind of pushback and were basically across the board fired from all of their jobs. Once this was publicised, the vast majority of them were given some kind of prison sentence even though some of those were reduced or overturned on appeal. It always appealed that he was standing in for something larger than just himself.

What’s the creative starting point for this then? How do you convert that story into a film?

It came about because I was commissioned by an organisation called Just So to make a short documentary and I had pitched one about this film because I had been researching it for a little while. So, they gave the initial funding for the film and I really imagined it as something I could turnaround in a couple of months precisely because it would be so simple and would just be these documents. In the end, it took close to two years on and off. Partly, because it was a challenge making that form visually legible, making it a satisfying journey visually as a viewer because it’s an unfamiliar form, it’s not a way we’re used to interacting with film. Also, it was so difficult to find any clear information about the case, what exists in the public record and online is limited and samey, so it took two years really to unpick all the misinformation. Especially because the first ports of call that I went to were the police, I requested all of their case files.

I went to the national archive and asked for all of the Director of Public Prosecutions files and each one was turned down and these files have since been sealed for decades to come. I had back and forth arguments with the Met Police trying to get them to release more information about the case but they wouldn’t. In the absence of that, it required a lot of lateral thinking. I’m really indebted to a small number of archives that have kept an amazing amount of really informative, clarifying material about this case. Specifically, the Bishop’s Gate archive and the Hall-Carpenter archive at the London School of Economics. Without those two, the literal materials of the film would not have been in my possession. It didn’t help that I’m not a professional journalist so I didn’t know all the go-to ways of sorting this kind of information, I’ve been very much learning on the job.

How much material did you have then in comparison to what ends up in the film?

Now, I have mountains. In the beginning, I knew nothing, I had the extremely inaccurate Wikipedia summary and the three independent articles that had been digitised and put online. Even when I went to newspaper archives and read the reports from the time, it was an extremely limited view of what went on. So, it took a long time to flesh that out. I’m still finding stuff, literally last week, months, nearly half a year after the film was, in theory, finished I went to the House of Lords archive at the Houses of Parliament and looked at the appeal documents of when the case was appealed in 1992 and it was an avalanche of information, much of which I’d either found by a much more circuitous route or had still been looking for all this time. That helped clear up some further questions in my head.

Has anyone approached you that has seen Lasting Marks but perhaps didn’t want to talk about it prior to the film, and revealed anything to you?

There is a small group of people who are still very actively involved in the case, most of whom were there at the time or have done subsequent research, and luckily I managed to reach most of them during the making. There were certainly a huge amount of people who remember it clearly from that time and remember what a seismic case it was in the LGBT community in Britain. Just for its precedence setting, if nothing else. The way the police were setting a marker and saying this thing that was hitherto thought to be private is now under our domain.

It felt very important to me to leave a certain amount of agency in the viewers’ hands so that they can question where I’m pointing them and override that guiding hand if they choose.

Creatively, how did you go about choosing the form of which to tell this story? It’s not the way we usually engage with art, and that could be said for all your documentaries in some way. They tend to avoid the generic means of telling these stories.

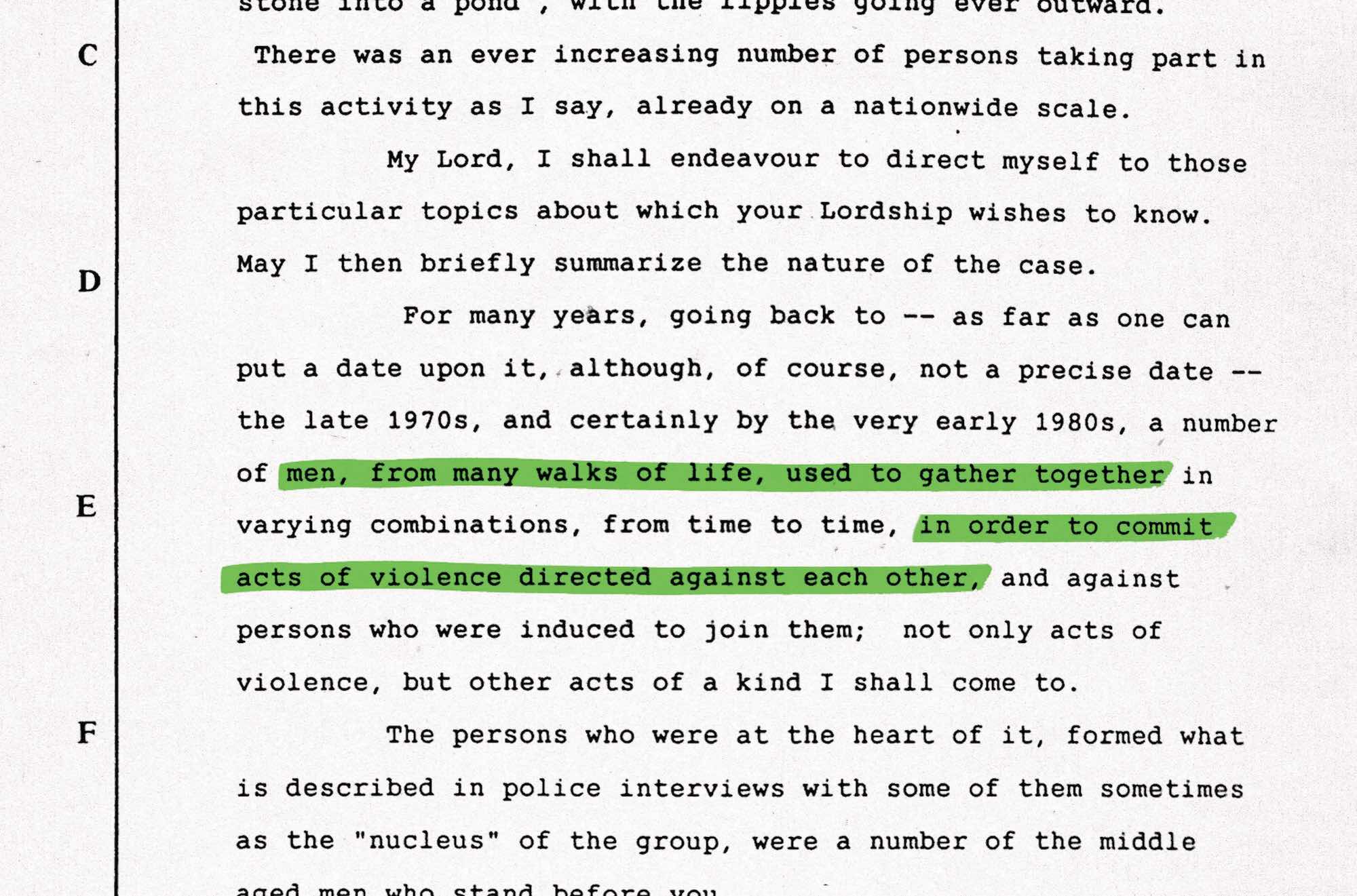

I think the earliest germ of the idea came from a frustration with the documentary device that when you get shown a document or an article or a piece of paperwork, you see it for half a second and then it gets blurred out and they bring a singular sentence forward and, clearly, it’s meant to be visually helpful. It’s meant to show the key information, like one sentence that fits neatly across the widescreen film frame. But, that always leaves me thinking about the context, like what is the document that you’re not wanting me to see, in favour of just showing this one line which you think is most apposite, and thought it would be quite a potent corrective to that to let people actively choose to wander the document if they so chose, and have the context and navigate for themselves.

Obviously, I make some compromises to that. I do highlight certain pieces of information to hopefully guide you so that there’s some correlation between what’s being said in the soundtrack and what’s onscreen. It felt very important to me to leave a certain amount of agency in the viewers’ hands so that they can question where I’m pointing them and override that guiding hand if they choose.

And finally, what are you working on next?

I’m at the very beginning of these two projects, my first scripted project and a documentary. I’m sorry to be vague but it’s at such an early stage where there’s not a word on the page or an image in a timeline. But I’m excited about both, and it’s kind of the best possible stage to be at with them because right now they’re just ideas and they’re perfect. There’s not a single fault with either project and the second next week that I have to start putting them into words and putting them onto the page I’m sure they will crumble. But, this is a good place to be.

You can read DN’s full coverage of BFI Flare 2019 here