The generation gap has always proved fertile ground for young filmmakers. Whether it’s reminiscing on days gone by or discussing differences in childhoods, burgeoning filmmakers find something fascinating in those members of the human race slightly nearer the finishing line. RCA graduate Dal Park decides to tackle more than just one gap with her experimental animation West Question East Answer, as she uses a failed interview with her Grandma to open up a larger exploration of generational and cultural differences.

When did you decide you wanted to make a film about your Grandmother and how did you decide on the premise we see in the final film?

The idea to make a film about my grandmother started when I was working on Prey, my first year film at RCA. Prey is a very personal short film about my mother’s death. It made me think back about my family and my background, considering the fact that I grew up as a second generation Korean in Germany. That’s when I went back to my grandmother’s autobiography, written 22 years ago. My grandmother was born in North Korea during the Japanese Occupation. She experienced the Korean War, was a refugee in South Korea and later went to Germany to study literature where she experienced the German reunification.

Her life was mainly determined by political events which she describes in her book. After reading it a couple of times I had so many questions about her life, especially her personal reasons and motivations for the tough life decisions she made. I wanted to find a bridge between this extraordinary woman in the book and the one who has always been my family and especially my grandmother. She was almost 90 years old (and is still going strong) and I didn’t want to miss a chance to ask her all the questions I had.

We were unable to communicate or understand each other even though we speak the same languages.

My initial idea was to make a short film based solely on my grandmother’s life. I went to Korea for three weeks, where she now lives, in the hope to have an intimate conversation with her. But our first conversation was quite confrontational. We were unable to communicate or understand each other even though we speak the same languages. She is quite protective about her personal life (I guess due to her life experiences) and she didn’t understand my ‘ignorant’ questions and how I would make use of all the information and the stories I was asking her for. It was very frustrating and a bit of a shock for me, as I felt I was hitting a wall. Having said that, I was quite intrigued by our communication issues. And while contemplating about them, I was inspired to make a film about these barriers instead. In many ways, it was about uncovering who she really was as an individual, understanding her and also myself, to break away from the prejudices I held.

Can you explain a little about the themes you were hoping to explore in West Question East Answer?

It was important to me to explore the gaps that can exist between two people. You can be from the same family but if you grow up in different generations and have different life experiences it can shape the way you see and think of the exact same situation. And this difference can result in big communication problems especially when you fail to really listen to the other person. Or even if you try, sometimes it’s hard to understand the other person just because you have had different life experiences and hold different perspectives due to the cultural or generational differences.

Additionally, identity especially ethnicity has always guided my work. While I didn’t explore it as the primary theme in this narrative, I attempted to subtly capture the nuances through my characters.

How did you go about recording the conversations with your grandmother? Did you have a certain line of conversation you wanted to follow or was it more organic?

Before I went to Korea I wanted to prepare myself really well. So I read my grandmother’s book three times, summarised it into a timeline and prepared 9 sets of interview questions referring to different subjects such as her childhood in North Korea, her adult life in Germany, the intersections of her gender and ethnic identities as well as her role in Korean society as a woman. My hope was to start off with a classical interview and then naturally move into an organic and intimate conversation that ended with a nice grandmother-granddaughter bonding moment. In retrospect, that sounds like such a cliched fantastical storytelling approach, no wonder it failed.

The first morning, while I was getting ready for the day, my grandmother handed me two books written by authors from the same generation and background as hers. She wanted me to read them as part of my research. But I tried to explain that I was with her to learn about her life and not the political context. This was the beginning of a 1.5 hour discussion about the interview before we even had one. We completely failed to communicate with each other. She did not understand my motivations and I did not understand her worries and objections.

Most of our moments together were in silence.

My dad tried to mediate between us, but that didn’t help either. However, during this intense exchange I pulled out my phone and recorded our first conversation. Most of the voice recording from this conversation was used in the final film.

The same night I placed all the material I had prepared back into my suitcase. I thought it would be best to approach her with a different strategy. I simply started hanging out with her, taking part in her daily routines while documenting everything. Most of our moments together were in silence.

She is quite particular about how things should be done in her house and each object, even a small piece of paper, has its exact place in the house. While I thought an interview would help me get to know her better, I realised that simply spending time with her and following her rules made me understand her better and get closer to her. And while I was watching her she was watching me and accommodating for me as well.

After a while, she started telling me stories or sang to me. Every chance I got, I would pull out my phone and start recording our conversations. And sometimes I would put a recording device on top of a shelf and record us having lunch or dinner for a couple of hours. In the final week she asked if I still wanted to do the interview. We talked for about 4.5 hours but I used none of the material as I was more interested in the exchange from our daily interactions.

With the audio recorded, how did you go about cutting it down to the 6-min film?

When I came back to RCA for my final year, I knew I wanted to depict the entire story of my visit to my grandmother’s house, even the conflicts. I put together a skeleton for the story and decided on the character arcs. I did not work with a storyboard but instead did free writing exercises for 20 minutes every morning during the first term. This exercise helped me reflect on the story I wanted to tell and select key moments. I animated these first.

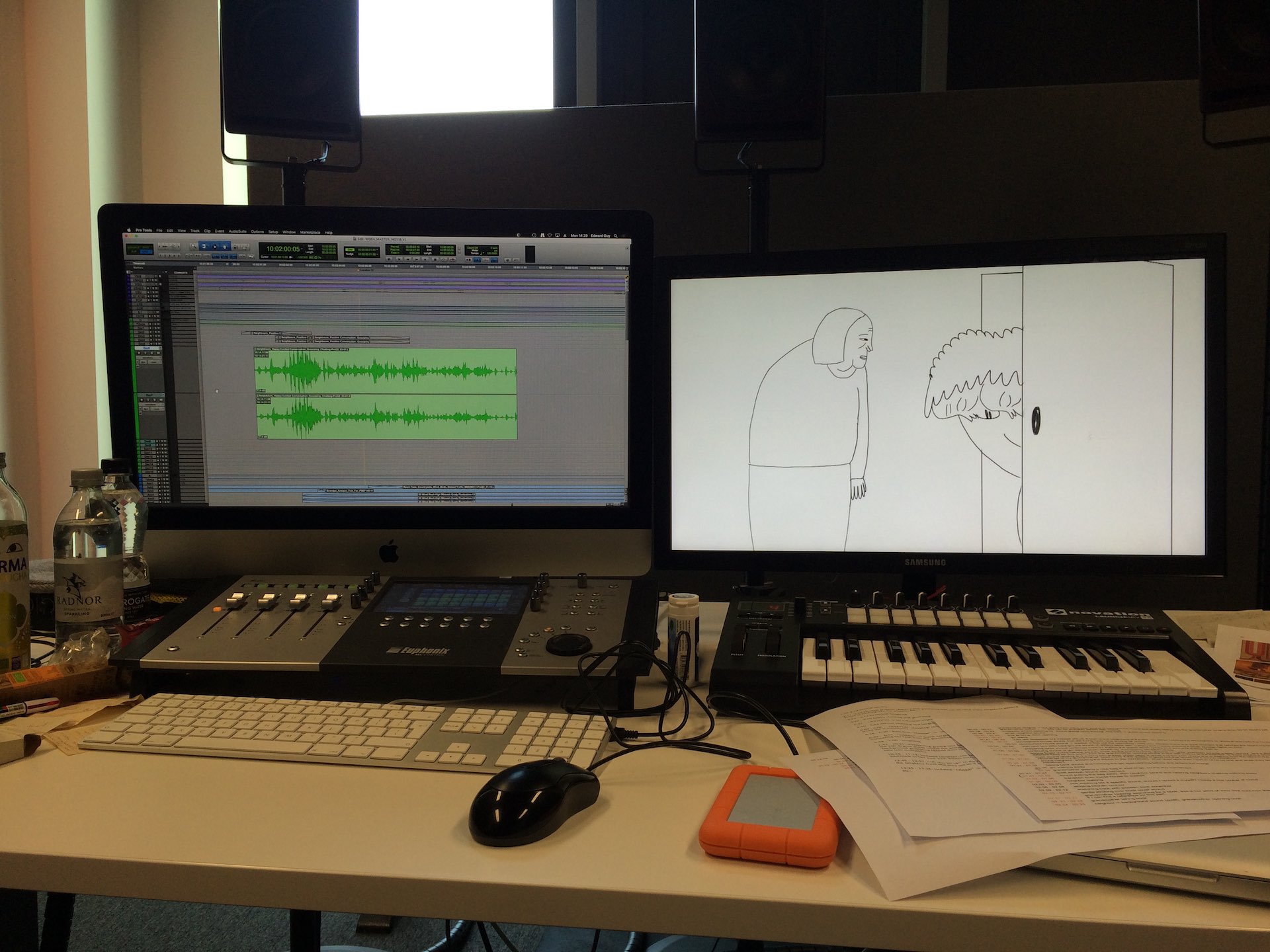

Then, I preselected some audio footage and typed it down. I worked with an amazing scriptwriter, Lydia Rynne, from the NFTS. After I briefed her on my story, she managed to pick single sentences from the written audio and stitch them together into a narrative structure that represented what I had in mind. Alongside this, she wrote the voiceovers. Based on the written script, I started to edit the images and the audio around each key moment I had already animated. It was quite an experimental approach and my film changed a lot each week. In the end, it all came together as a 6 minute long film.

What’s the significance of the frog and the neighbour characters in your film?

Well, the frog doesn’t have any particular meaning. I made it just for fun when I needed a break. But it turned out that he was quite a popular character during our Work in Progress Show so I just gave him a small part.

The neighbours, on the other hand, play a very important role in the film. My grandmother lives in the countryside where all houses are open and the Korean society is quite communitarian. So almost every day the neighbours would just drop in for a chat or bring some food. The interactions were quite friendly but gossiping seemed to be an integral part. And information seemed to move quite quickly in such a small village.

The neighbours represent my subjective and quite critical view of the Korean community.

In my film, the neighbours represent the reason why the granny does not want to open up. She is scared that the information could leave the house and be misused. At the same time the neighbours represent my subjective and quite critical view of the Korean community I interacted with in Germany. As a child, I had to go to Korean school every Saturday and I perceived everyone as gossipy and nosy and I refused to be a part of such an intrusive community. When I met my grandmother’s neighbours in Korea all the emotions and memories from my childhood came back to me. So I wanted to portray these intricacies in my film.

The neighbours in my film are also compared to mosquitos who are constantly intruding into the house, sucking your blood and always creating unnecessary noise in your ears. After all, it was quite a hot summer in Korea and I came back with mosquito bites all over my legs.

Let’s talk about the aesthetic, why did you decide on this particular look?

The RCA made me re-discover my love for hand drawing. I definitely wanted my film to be done with acrylic as I love the texture and the boiling it creates in animation. At the same time, I wanted to spend as much time on the storytelling as possible. So I decided to keep it rather simple and minimalistic to not only have enough time to work on the story but also get a chance to make a hand drawn film.

The film was made during your studies at the RCA, what effect has your time there had on your filmmaking?

Before I started at the RCA I had no idea about the process of making a film. During my undergrad in communication design I pursued interaction and service design. After completing my BA I chanced upon an internship as a production assistant. That was my first step into the world of moving images. Thereafter, I interned and worked as a motion designer. Here I learned a lot about the technical side of animation and realised that I wanted to learn more about storytelling. The RCA definitely helped me with that and showed me so many possible ways of telling a story.

A short film only has a few minutes where you need to tell the whole story.

Both films I made during my MA are very personal and based on my experiences. It is sometimes hard to translate personal experiences into a film and be objective about storytelling decisions because you think to yourself “but this is how it happened”. The RCA has helped me find techniques that helped me to detach myself as a filmmaker from my real life experiences. What I mean by that is, I don’t attempt to portray my experiences exactly but rather I am inspired by them and make decisions that help the storyline and the characters. This was quite crucial for me since a short film only has a few minutes where you need to tell the whole story.

I also loved the fact that I met so many exceptionally talented and enthusiastic people in my programme. Everyone is so unique in their own way. This and the weekly one-to-one sessions with the tutors definitely helped me become more confident. It encouraged me to follow my interests instead of second guessing everything and to experiment more.

What are you working on next?

I am currently researching for my next film idea that bears a close parallel to my first year film. I am investigating about our attitudes towards death and looking into our contemporary and ancient relationships with the act of dying, mourning and death rituals. The summer before I started studying at RCA, I worked as a funeral assistant. In the past few months, I have also had the incredible opportunity to volunteer at St. Joseph’s Hospice in London. I would like to utilise a combination of both, my experiences and research, in my next short film.

She didn’t understand my film or what exactly it is that I do for a living but she seemed happy.

Final question – has your grandmother seen the film and if so, what did she think?

Yes, she has watched it. She got quite emotional when she heard her own voice singing. She said she didn’t understand my film or what exactly it is that I do for a living but she seemed happy. She wanted to have some of my frames and they are now hanging in her house next to some family pictures.