Technology has reached a point now where artificial intelligence dominates a large part of our daily lives. But what happens when that very technology is employed for weaponised purposes and the decision of whether a person lives or dies becomes an algorithmic puzzle? Matthew Harmer’s new documentary Immoral Code (which was edited by DN’s own Serafima Serafimova) posits these very questions, centring a look at the potential of autonomous weapons alongside a social study where people are asked ethical questions surrounding the value of human life. It’s a clever documentary that subtly highlights the nuance required to answer such life-altering questions. DN caught up with Harmer as Immoral Code arrives online to discuss how he became involved in this project, his decision to centre the conversation around a social study and the visual tricks he employed to emphasise the morality at play.

Where did the concept or your interest in making a film about the use of artificial intelligence in weaponry begin?

So I wasn’t actually involved in the project when it initially all began, way back in late 2019. Nice and Serious, the production company/creative agency who produced the film, had been commissioned by the NGO Stop Killer Robots to create a short documentary about the subject of autonomous weapons, specifically weapons that could make the decision to use force or kill without human control. It was Serafima Serafimova, the editor of the film, and Rickey Welch, one of the producers, who came up with the concept of creating a social study that looked at the subject from a moral point of view, exploring how human beings cope with moral dilemmas, particularly decisions around life and death, with the overall aim to show these decisions are far too complex for a machine to ever make. Essentially making the point that you can’t code a machine with morals, you can’t programme a computer to understand the value of human life.

What did the initial discussions surrounding how that would play out visually involve?

I’ve been working with Nice and Serious on and off for the last five years and used to work there full time before that, so once the project went into pre-production, we started discussing a few ways we could approach the filming, the sort of interviewees we could feature, and they then officially brought me on to direct. We started working out which experts we’d like to feature. For example, I wanted to interview someone that had actually been in a conflict situation, someone that had had to make the decision to take a life, so we could understand the moral complexity of it. Just as we got close to setting up our first shoots, Covid struck, and everything got put on hold. Apart from the safety aspect, particularly in regard to the social study which was going to involve lots of different people coming into the same space, many of the interviews were with older people, and I definitely didn’t want to do any recording over Zoom, I really don’t like the aesthetic! So we waited.

When did you pick everything back up?

Fast forward one year, through the pandemic’s various waves, and it looked like we were in a position to pick things up again. We found a really interesting space to shoot the social study, a robotics lab in London, and we managed to cast a really varied demographic of participants for the study itself.

Those question segments do a great job of conveying the moral weight of the subject. What was your inspiration behind the visualisations of that element of the documentary?

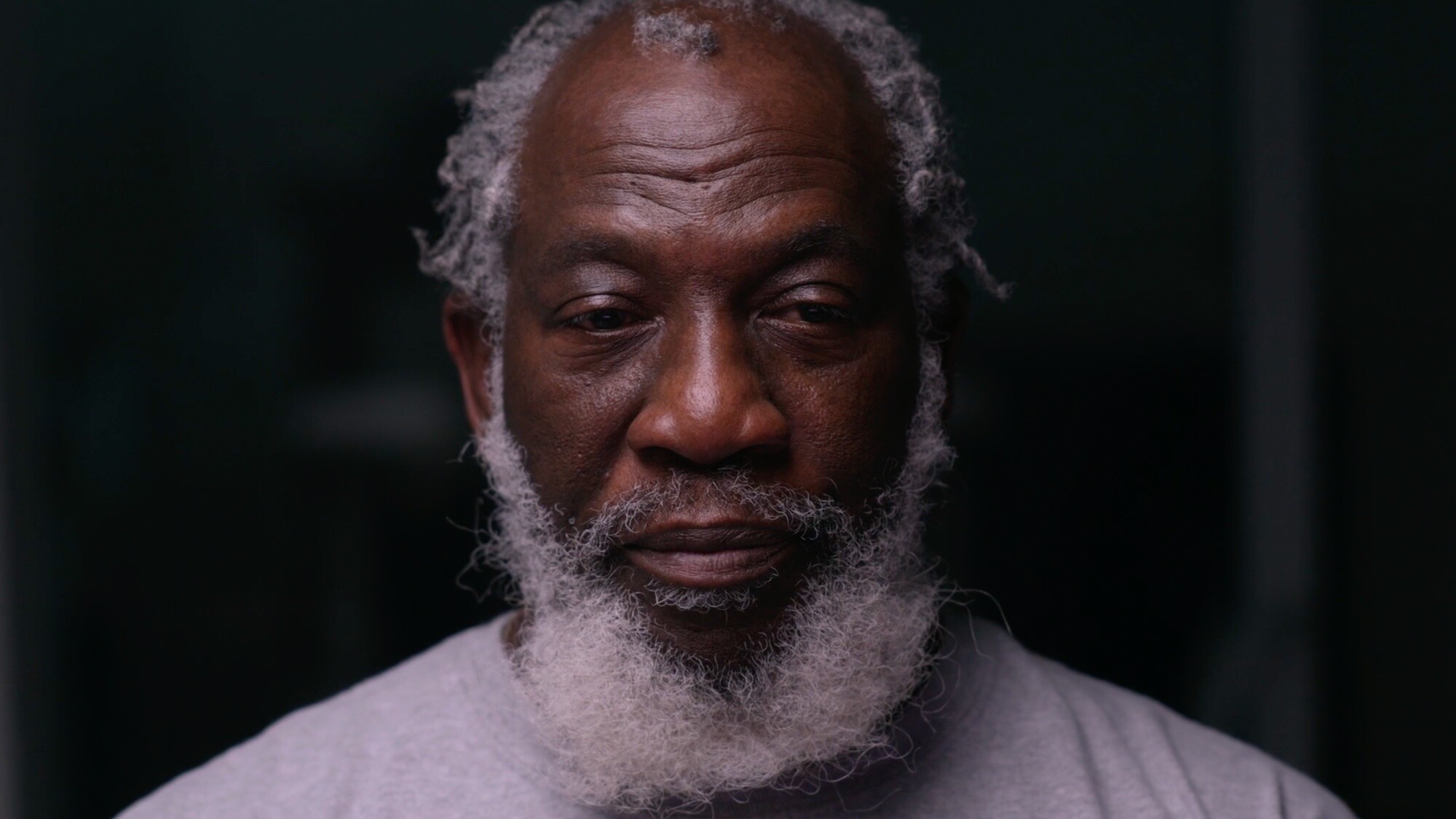

The social study element is really the main part of the film, it’s what everything else is structured around and is the film’s point of difference, so we really put a lot of the budget into making it look good. Our DP, Peter Emery, favoured the Sony Venice as our A-Cam, mainly shot on the Nikon Nikkor AI-S 85mm 1.4. What I really wanted to achieve with the look of the social study was to emphasize the importance of human decision making, and to frame it as a positive thing that we need to hold onto in society. So I wanted to give the social study a really rich, saturated, warm look, and using the Venice in combination with a portrait lens like the 85mm, helped achieve this and make everything look as beautiful as possible. Due to budget constraints, we sadly couldn’t shoot with the Venice and Pete on all of the expert interviews, and so these were mainly shot on the Blackmagic Ursa Mini Pro and Blackmagic Pocket CC 6k with me self-shooting.

What I really wanted to achieve with the look of the social study was to emphasize the importance of human decision making.

Another thing I wanted to work into the social study shoot was this building tension as the questions developed and the dilemmas got harder. So for the first set of questions, which are slightly whimsical in parts, as well as to give some context of the location, we framed the participants on a mid-shot. However, as the questions progressed and got tougher to answer, we moved the camera in and used a tighter frame, part of which helped build feelings of claustrophobia, tension and intensity, but also placed more emphasis on the participants’ facial expressions, allowing you to see the emotions and thoughts they were battling with as they contemplated these moral dilemmas.

I’m curious to know what influenced the cutaways of the data sets? They seem more intricately composed than your typical b-roll.

In terms of shooting the b-roll elements, we wanted to incorporate a few different ideas, one of which was to create a physical representation of a data set, inspired by an exhibition by Anna Ridler. Data sets are what are used to program artificial intelligence systems and are, essentially, lots and lots of data points, for example images which you show an AI system so it can learn to recognise something. So we created a moc data set that an autonomous weapons system may use to recognise potential targets like human beings or urban areas. We also experimented with using a probe lens to film the inside of computers, as a way to contrast the decision-making system of a computer, microchips and wires, with the human mind.

How was post-production in general and piecing all of these different sections together?

Post-production was a fairly disjointed process, and we actually edited the social study before we shot any other parts of the film, structuring it into three sections, and then used this to help us plan the content of the expert interviews that made up the rest of the film. We then cut these down and combined them with the social study sequences into a fairly solid content cut, before doing a final shoot to record the visuals for the title sequence and various b-roll elements. This perhaps isn’t the typical process, whereby you normally shoot everything before going into the edit, but I think it allowed us to be a lot more efficient and informed on the final shoots, particularly with the b-roll.

With the grade, we subtly accentuated the look we shot for in the social study, keeping everything warm and rich, and then we contrasted this with a dark, slightly desaturated look in the expert interviews, which represent more of the ‘machine’ side of the story. I guess you could bluntly say the social study represents the human-centric part of the film, and the expert interviews/b-roll represents the machine-centric part of the film.

You can’t code a machine with morals, you can’t programme a computer to understand the value of human life.

What future films or projects do you currently have lined up?

I’m currently finishing off a short film series with The Waterbear Network about conservation heroes around the world. We’ve got three more films to complete on that and then I have a few ambitious ideas which I’ve had up my sleeve for a while which I want to develop and try to get commissioned/funded. And I’m constantly working on various branded content projects!