Created as part of the BFI & BBC’s Animation 2018 talent scheme, topical stop-motion short Quarantine focuses on a troupe of Morris-dancing badgers forced to confront the animals quarantined in a facility built above their burrow. Joining us to discuss the importance of fabric choice and funding, Director Astrid Goldsmith explains why she chose this storyline and what she hopes an audience takes away from her unusual short.

Quarantine was made as part of the BFI & BBC’s Animation 2018 talent scheme, how did you get involved with this and what did their backing mean for your film?

After surviving the various battles of self-funding my first film, which took nearly eight years of solitary confinement in my garage, I was definitely on the hunt for some support for my next film. UK animation funding is pretty thin on the ground, so when I saw the Animation 2018 scheme being advertised, I wrote a story and drew some badgers as fast as I could! They interviewed 24 applicants out of the 300 submissions, and I was asked to bring a badger puppet to my interview so they could see what they would look like in 3D.

Normally it takes two weeks to make a finished puppet, but I only had four days before my interview, so I knocked up an extremely ropey prototype badger, using an old pair of black tights for his fur. I was overjoyed when Quarantine made it to the final selection of 13 films, not only because I would get to make another film, but also because it would be shown at the BFI and on BBC4, two of the most prestigious platforms for film in the UK. It felt like the best possible pat on the head!

The notes I received from the scheme’s executive producers really pushed me to be a better filmmaker, and the funding made it possible for me to employ a small crew for the first time, which was brilliant and very necessary given the tight timeframe.

You describe the film as a “post-Brexit pagan dance fantasy, about a troupe of Morris-dancing badgers on the south coast of England” – can you expand on this for us and explain where this story came from?

When I started thinking about the idea for Quarantine, I stumbled upon a news story about the impact of Brexit on transporting animals abroad, as the UK would no longer be part of the EU Pet Passport scheme. The article stated that the kennels and animal quarantine facilities at UK ports would be overrun, and measures must be put in place to ensure the humane treatment of animals.

I wanted to interrogate that notion of what we consider to be the ‘humane’ treatment of interned people.

I live in Folkestone, on the south-east coast of England, which is the closest point in the country to mainland Europe (on a clear day you can see France from the end of my road). The Channel Tunnel terminal is in Folkestone, and the ferry port of Dover is just down the road, so I was interested in exploring what it would mean to live in a new border town once we leave the EU and the border moves from Calais. I wanted to interrogate that notion of what we consider to be the ‘humane’ treatment of interned people, not just basic requirements for survival but also support, love and exchange.

Music and dance are international languages, and seemed like a good way to tell this story in a dialogue-free film – Morris dancing is a tradition specific to Britain, but the language of folk dance and song is global, particularly the accordion/melodeon, which features in many different countries’ folk music.

Brexit seems to be a popular subject with British filmmakers at the moment, what made you want to tackle the subject and what do you hope viewers take away from viewing your film?

The Animation 2018 brief was something along the lines of ‘what do these films tell us about Britain today?’, and they encouraged us to submit ideas which engaged with topics of national or global importance. As the child of immigrants and the grandchild of German-Jewish refugees, the immigration narrative has been central to my life and work, and I can feel the wheels of history turning full circle with Brexit as we move away from a peaceful, unified Europe.

I wanted to write something that projected a somewhat hopeful vision of post-Brexit Britain.

Kent had a 63% rise in hate crime post-referendum (the 7th highest rise in the country), and it made me very anxious about the future, particularly with stories surfacing all the time about the inhumane treatment of people held at Yarl’s Wood and other detention centres. Nobody knows what’s going to happen, the government has been in a state of flux since the referendum, and every day the news brings more uncertainty and doom. I wanted to write something that projected a somewhat hopeful vision of post-Brexit Britain, something which acknowledged the reality of detention centres whilst at the same time making a case for continuing cross-cultural exchange.

Can we talk a little about the aesthetic of the piece, it has a very tactile look to it, was this feeling of ‘real’ characters something you feel was important to the success of your film? And what do you think stop-motion adds to the piece that 2D or 3D computer-generated animation couldn’t?

Because Quarantine is largely about folk tradition and nostalgia for Merrie England, it made sense to me to use a medium which reflects that, with handmade craft techniques and a style of animation reminiscent of 1970s children’s TV. I really love materials so in general, I find it hard to connect with the unreal surfaces of computer-generated animation.

I tried to use the most tactile fabrics I could for the puppets’ ‘fur’, while still retaining a clean outline of the character. A lot of stop-motion puppet design is dictated by the demands of the medium – any surface covering has to be a 4-way stretch fabric so that it won’t restrict the puppet’s movement, and you have to avoid any long-pile fur fabric if you don’t want the puppet to look like it’s standing in a wind tunnel for the whole film – so I was delighted when I found the stretch terry-towelling that I used for the badgers’ white patches. Apologies for the really specific fabric geek-out!

If you know how a puppet would feel to touch, you care more about what happens to that character.

But it’s those things that can really help a character feel real, as everyone knows what terry-towelling feels like and for most, it will have strong unconscious associations with childhood, softness, comfort. I think if you know how a puppet would feel to touch, you care more about what happens to that character. Also, your awareness of physical gravity in stop-motion adds to the humour on screen, there is something about watching an overweight badger leaping around with a hankie which is kind of unexpected and funny (hopefully).

The film was made over 21-weeks, can you tell us about the production – who did you have working with you? what tools/equipment did you use?

It was a very intense work schedule! It’s a 13-minute film, with 14 puppets, a lot of sets and countless props, I was very anxious throughout the production that I wouldn’t finish it on time. I was working 16-hour days, seven days a week, for five months – I’m sure most animators know the feeling!

I was very lucky to have two incredible local model makers working with me for the first two months: Hetty Bax – who worked on Isle of Dogs and Anna Mantzaris’ new film – made the props; and sculptor Adam Hynes – who has made work for Jake and Dinos Chapman among others – built the sets.

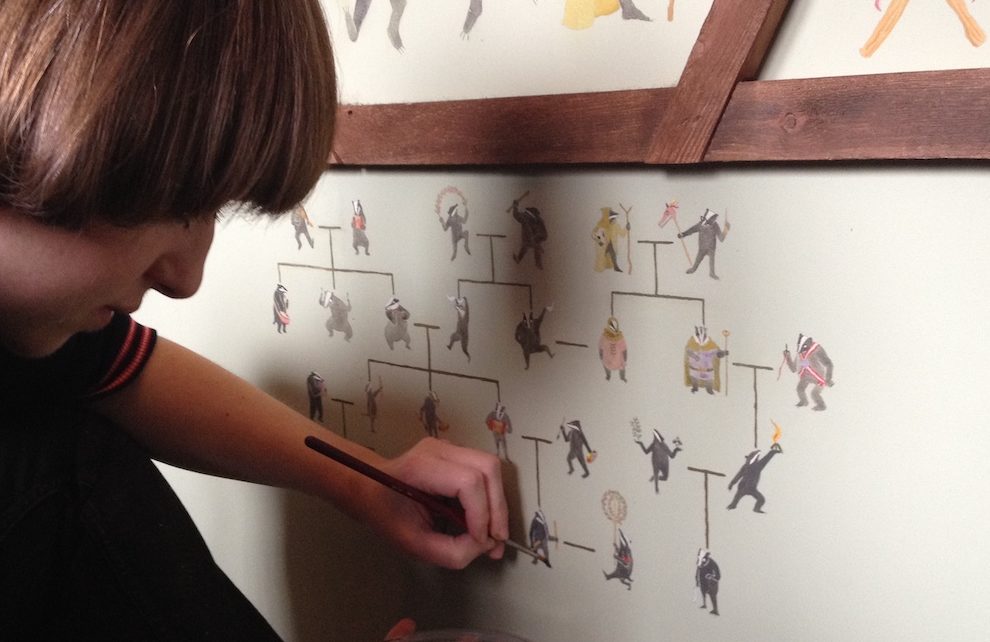

I made all of the puppets from aluminium wire, furnishing foam cut with nail scissors, and hand-carved balsa wood heads – very lo-fi as there was only a tiny materials budget (£9 per puppet), and no time for moulding and casting or the luxuries of back-up puppets. In the last week of filming, the main badger broke both arms and one leg – the aluminium wire finally gave out and snapped clean through – and I had to cut open the fabric skin and Frankenstein him back together with epoxy putty so I could finish the shoot.

There were some more hi-fi elements of the shoot – I shot my previous two films on a 1969 wind-up 16mm Bolex camera, but there wasn’t enough time or money for developing film, so I finally caved in and switched to a DSLR and Dragonframe, which was a tough adjustment for me. I was animating in the garage under my house, and two floors up my partner-in-crime/live-in Composer Craig Gell was writing the score in his studio (aka the spare bedroom). My Editor Anna Dick lives just down the road, so it was a very local production. Being stuck inside an airless dark room for months – animating under lights during the hottest summer on record – was pretty gross, but at least in Folkestone you can jump in the sea at the end of the day!

What are you working on next?

I’m writing my next film, a feature-length stop motion monster movie set on Mars. I’ve been fully immersed in research and development, reading a ton of 20th-century science fiction, watching a lot of early John Carpenter movies, and obsessively tracking the NASA InSight Lander’s progress on the planet. I’m currently investigating ways of getting it made so that I can afford a proper crew. I am full of admiration for outlaw-animators like Christiane Cegavske, making independent features pretty much on their own, but the dream is to set up a sustainable stop-motion studio in Folkestone, not just me in my garage. It would be great to have a bigger space to accommodate large-scale sets and enough work and funding to support a whole team of local artists and animation graduates. Here’s hoping!

Quarantine is currently available to watch for free on the BFI Player