An exquisite celebration of the triumph of love over fear expressed through a beguiling combination of dance and light, Sydney-based-Dublin-born Director Sinéad McDevitt’s The Ocean expresses the ways in which Irish musician Wallis Bird’s universe expanded as her connection to her lover strengthened. Below Mcdevitt takes us through the development of this collaborative project which encompasses music, film, dance and VFX and was intended as a gift to the LGBTQ+ community, who all too rarely get to experience powerful same-sex love stories on screen.

What connections did you see between your work as a filmmaker and Wallis Bird as a musician that prompted you to pursue a collaboration with her?

Great question and a really tricky one to pin down. The initial prompt was the fact I just couldn’t stop playing Wallis on my iPhone. A gut feeling grew, through listening to the themes and stories in her music, that we could be creative kindreds.

Songs about facing her dark side, celebrating the bright side and cherishing everything beautiful and scary in between set up camp in my ear canals and wouldn’t budge. Here was an artist who really wore her heart on her sleeve, bullshit-free. It just struck me as being so ballsy because she’s taking a risk with every tune she writes. That vulnerability may fall on deaf ears or it might shoot straight to the heart. She just says *f*ck it” and goes for it with every track she records.

I think any artist who sings about stuff the rest of us lack the bravery or language to express is incredibly ballsy and so generous. Maybe because it gifts us with permission to look at or confess what‘s frozen inside our own bodies and minds. And in doing so, melting it just a little bit. I really do feel like art and therapy are one. There’s Wallis belting out a song about her inner demons through our earphones. We listen and a little voice rises up from the depths, heaves a sigh of relief and whispers “phewww… thank christ… it’s not just me”.

I really do feel like art and therapy are one.

That’s absolutely what I would love to achieve in my work as a filmmaker; to create a strong connection with the audience that reminds us we’re not alone in our quirks or loves or struggles. That we’re far more connected than we think. That all of us have frozen bits in need of melting.

I feel like the only way to do that as a filmmaker is to be brave in the ideas we pursue and the choices we make. Around the time of writing the treatment for The Ocean, I heard director Aoife McArdle sharing one piece of advice for directors and it was simply “Be Bold”. I loved that. Her words fuelled me to take a creative risk with The Ocean. I’d never directed a dance film before, but I thought f*ck it (channelling Wallis-spirit) – I know how to tell a good story, I’ve been a designer for years. I want to direct this film with a designer eye. It also helped that a big side passion of mine is contemporary dance. Dream project.

Some of my favourite directors display that lovely Venn-diagramesque sweet spot of boldness and empathy in their work; the likes of the incredibly dexterous Alfonso Cuaron, visually luscious Luca Guadagnino, designerly Kim Gehrig, king Wes Anderson.

You’ve spoken of the impetus for The Ocean being a dearth of powerful same-sex love stories on screen – particularly during your younger years. What do you feel has been lacking in the rare examples of same-sex relationships which you wanted to address in this film?

Growing up gay in Dublin, the portrayal of LGBTQ+ relationships onscreen was incredibly rare. Whenever I stumbled upon a scene or soap opera narrative as a teenager – invariably on Channel 4 (UK) after midnight – I recorded and replayed it over and over like an overly-excited weirdo kid, alone in the TV room with the volume down. I found one! That’s me! I’m not alone!

Frustratingly, the only other place to find lesbian narratives back then was at the local video store I worked in – on the bottom shelf, labelled ‘adult’. That *could* have been a perk to the job, alas they were all rated ‘M’ – and therefore barred from my young eyes. Sheepish older males who avoided eye contact and slid crumpled notes into my hands at the till, were the exclusive fanbase. Side story: one Friday night, I took matters into my own hands and sneaked vintage classic Desert Hearts into my backpack for the weekend. Finally! A feature film that depicted a beautiful love story between two women. Directed by Donna Deitch, the story felt tender, authentic and planted my teenage gay brain with a month’s worth of romantic daydreaming.

Fast forward to 2019… and it’s a much brighter landscape now in terms of the onscreen depiction of authentic lesbian connection (apart from Blue is the Warmest Colour, which made me do a mini vomit in my mouth. So inauthentic and over-sexualised… I didn’t buy it at all).

Director of The Bisexual series, Desiree Akhavan, commented recently that “everyone under 25 is queer” now. So true. Gay is already practically stone age. Queer is the new normal. From Carol and Disobedience to The Favourite and Kyss Miig, same-sex narratives are permeating every genre in sight. Elsewhere, it’s becoming such a non-thing, that it’s no longer a film’s key selling point. Which I love. With Booksmart, Olivia Wilde weaved in lead character Molly’s sexuality in such a beautifully understated way that we don’t even blink when it emerges she’s gay.

Despite all of this amazing progress, the fetishisation, invisibility and persecution of lesbian and bisexual women continues around the world. Lesbian porn continues to be produced by straight male directors for straight male consumers. Homosexuality is still illegal in 72 jurisdictions around the world. 44 of those specifically criminalise sex between women. In the other places where it’s illegal, it’s not even recognised as a valid sexual orientation – essentially rendering hundreds of thousands of relationships invisible; a throwback to antiquated colonial laws in certain spots.

We clearly have a long way to go and I believe storytelling is crucial in igniting sparks of progress.

So I feel like while we’ve made huge strides with same-sex representation in ‘western’ film, it doesn’t mean we should rest on our laurels and stop creating work that explores authentic same-sex connection. Especially films that celebrate the sacred, shifting focus away from the sexual. Others are listening; both the ignorant and the abandoned. Much of the LGBTQ+ community continue to struggle with ostracisation by their families, friends, religious communities and governments. The recent family rejection story of everyday American student Emily Scheck in Buffalo, New York was one such story. We clearly have a long way to go and I believe storytelling is crucial in igniting sparks of progress.

The are several disciplines working together to fulfil a collective vision here – how did you select and rally your various collaborators in order to achieve this project?

Firstly, by writing a treatment I wholeheartedly believed in and really wanted to see come to life. I feel like when you share that kind of treatment with potential collaborators, they can sense that it comes from a real place; that you’re not faking it.

Secondly; by being open with our intent. Wallis and I wanted to make The Ocean, in part, as a gift for our younger selves who struggled with our sexuality growing up; but most importantly for those who still struggle, especially in those countries where homosexuality is still a crime. I was open about this intention when reaching out to various potential team members. Thankfully, it resonated with some absolute gems.

We were incredibly lucky with the amazing artists and crew who said a big yes to jumping onboard; from our DoP Ash Barron ACS to choreographer Yukino McHugh, dancer Liv Kingston, flame artist Jonathan Wendt and the film studio at AFTRS. Being completely honest, it kinda magically flowed from beginning to end. I’m still so grateful to everyone!

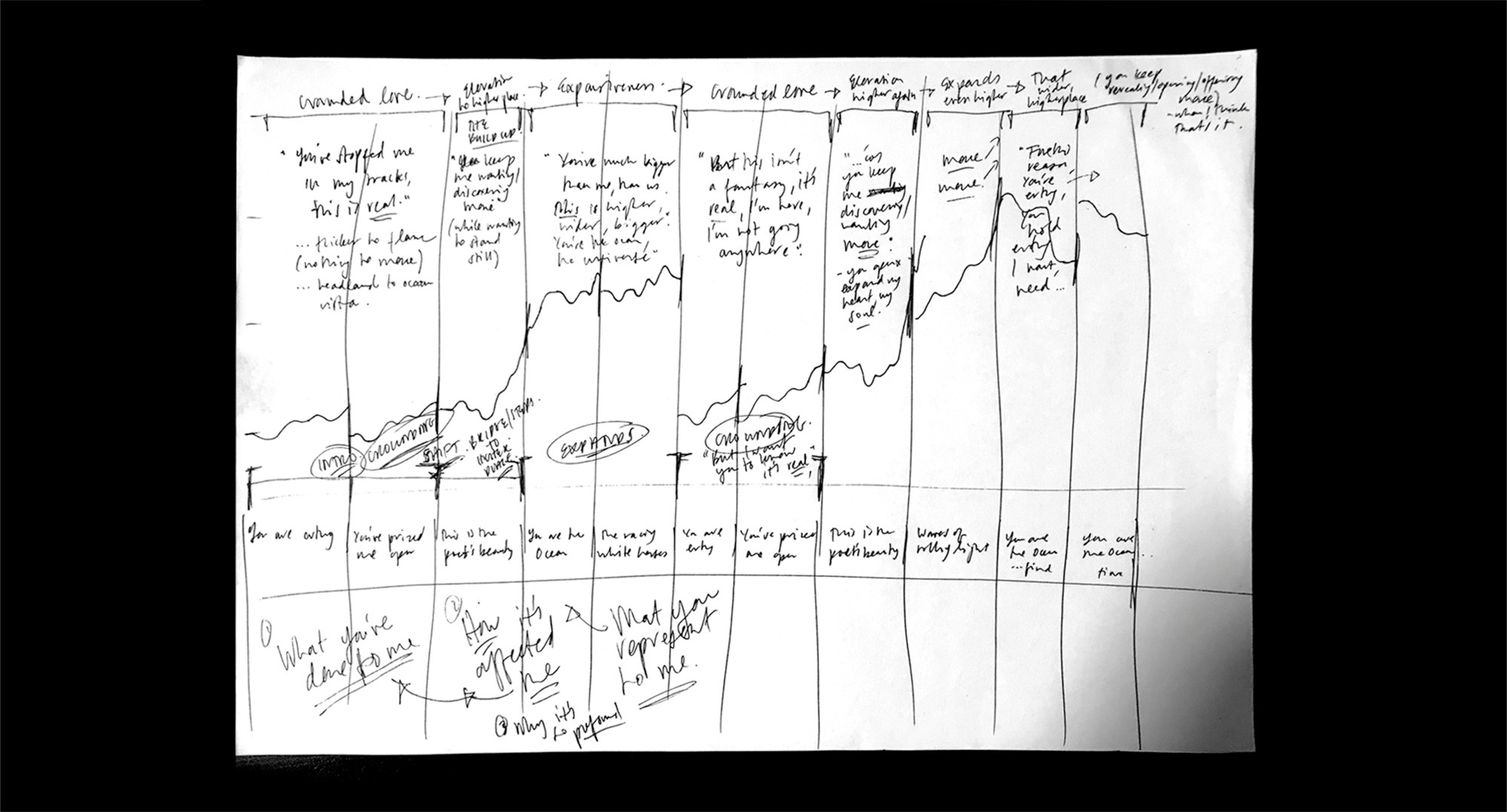

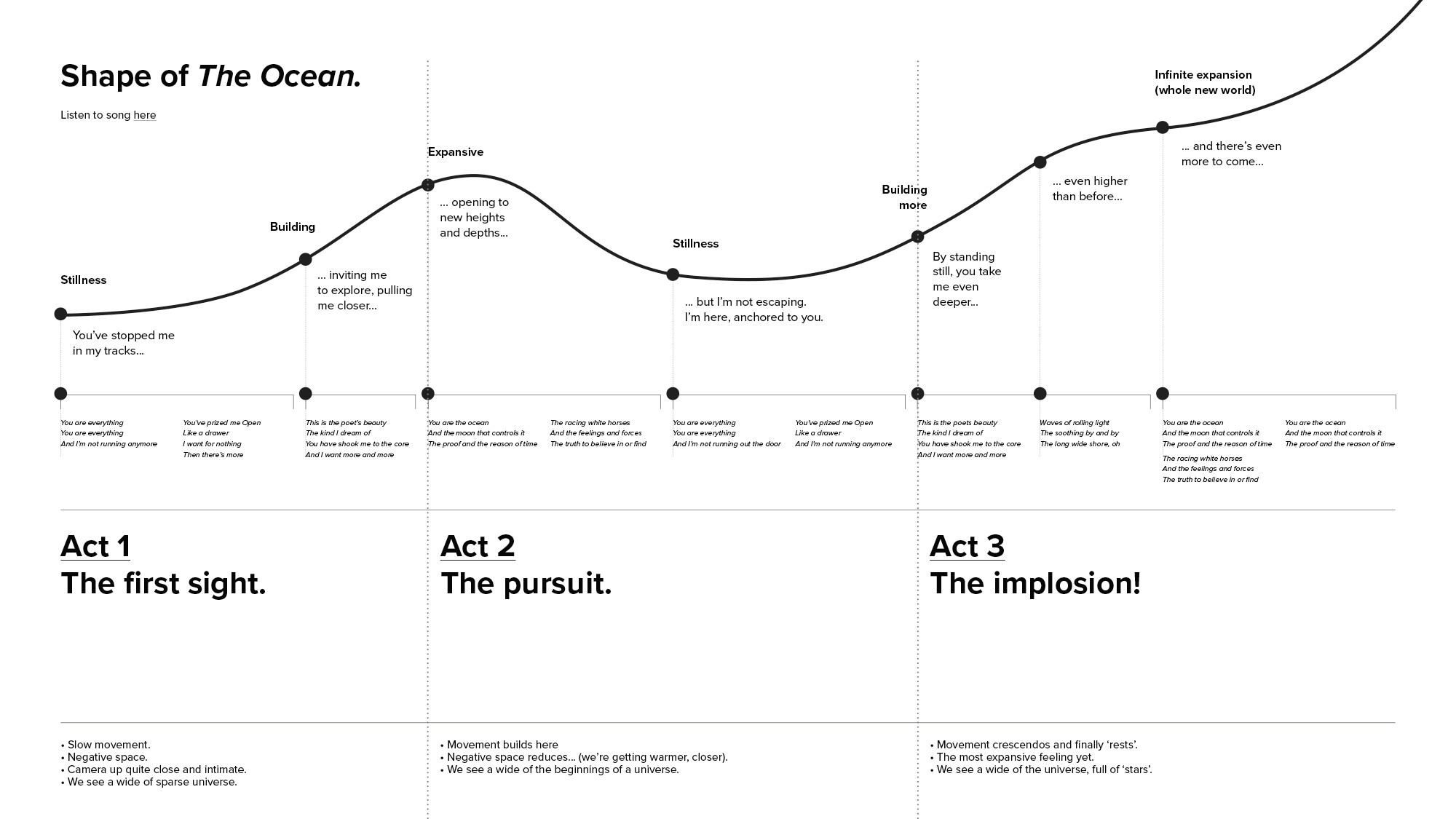

Could you tell us how you drew from Wallis’ real life love story and the song’s lyrics to plot the shape of the film over three acts and how that foundation, in turn, influenced the elements of the video which followed?

When Wallis first mentioned The Ocean – a new devotional song to her partner Tracey – I prodded her on the inspiration behind it. “Looking at Tracey is like looking out on an ocean of planetary systems,” she mused.

The image wouldn’t budge from my brain. I began to see the film play out in a mini universe of magical realism; feeling both expansive and intimate. I felt there should be a gravitational pull of sorts, a dance between camera and lovers. Building in strength to a crescendo as their connection matures from fantasy into reality… darkness into light… fear into love. I felt like their universe should ignite and expand the more they connect with each other. A key lyric in the song is “this is the poet’s beauty, the kind I dream of”, so a moonlit dreamscape felt like the strongest fit.

I felt there should be a gravitational pull of sorts, a dance between camera and lovers.

With this visual architecture in place, I then did a bunch of deep-dives with Wallis on her relationship. A three-act structure emerged as we charted the course from the moment she met Tracey (Wallis was sitting on the kitchen floor of a house party in Berlin feeling blue when Tracey walked in. She jumped up, transfixed)… through to the ensuing pursuit (Wallis trying to convince Tracey of her feelings over the course of 6 months)… and finally the letting go (Tracey finally melts and dives into love’s invitation).

We talked about key moments where their relationship shifted up or down a gear, as well as their own special body language (specific gestures they offered each other to relax); and how Tracey made her slow down and appreciate simple beauty. I then paralleled Wallis’s real-life love story with the feeling and lyrics of the song itself, to plot the emotional ‘shape’ of the film. Once plotted, this shape formed the basis for all decisions from there; movement design, colour palette, lighting, cinematography, frame rate, when/how the universe would come to life and design of the orbs themselves.

Did you pull any inspiration from mainstream depictions of dance and lovers when developing the style and form of The Ocean with DoP Ash Barron?

Yes, we sure did. Both mainstream and not-so-mainstream.

I started with sculpture and painting. In the song, Wallis compares her partner Tracey to Gala – Salvidor Dali’s real-life muse – so the movement and cinematography felt like it should evoke this sense of adoration, in an almost timeless, classical way. The idea of freeze-framing, or cutting to slow motion at certain points, started bubbling up. Maybe this could help convey that dreamy falling-in-love feeling of time slowing down. So a lot of my first visual references featured classical marble sculpture; beautiful, almost balletic figures frozen in time. Roman muses Terpsichore (the muse of dance) and Sappho (poetry) as well as The Kiss by Rodin nudged me to pay attention to their form.

The all-white wardrobe was inspired primarily by the portrayal of Gala in Dali’s painting The Madonna of Port Lligat. Applied to the context of The Ocean, simple white clothing represents the purity and authenticity of the lovers’ connection. I wanted to say that their love is sacred, transcending what some societies deem to be ‘good/normal’ love and ‘bad/abnormal’ love. It’s felt to me for ages now that an inappropriate preoccupation with the sexual aspect of queer relationships has created disgust and fear where there should be none. The Ocean calls on the viewer to focus instead on the transcendent beauty of a real, loving human connection, free of fear and shame. The choice to make it underwear/nightwear was a natural one, given the moonlit dreamscape. Also; a nod to Tanya Chalkin’s iconic Kiss photograph from the 90s, with gender identity dialled up through the style of underwear chosen for both characters.

I wanted to say that their love is sacred, transcending what some societies deem to be ‘good/normal’ love and ‘bad/abnormal’ love.

Once enough initial references were collated, DoP Ash Barron ACS and I got stuck into building the overall cinematographic approach. She is an amazing collaborator, always bringing really interesting suggestions and ideas to the table. First off: we knew what we definitely didn’t want! The world of short dance film online is drenched with the documentary-style approach; essentially a Movi or Steadicam that moves around the dancers in a space, documenting pure movement. Great for dance addicts. Absolutely the wrong fit for The Ocean. I wanted this film to be a love story that happened to be told in dance, so it needed to immerse the viewer in story of the relationship (as opposed to a pure performance) from the beginning, so they could feel the chemistry and the growing connection from first touch… through the moments of trepidation… and finally, the letting go.

And so we looked to feature dramas. I absolutely loved the blueish colour grade, emotional authenticity and intimacy in Call Me by Your Name – a key reference. Among a bunch of others, we also took inspiration from the slow pace, camera angles and milky grade of Carol; the timeless romance of the planetarium scene in LA LA Land (*sigh*); and a couple of iconic dance moves from Dirty Dancing thrown in for good measure too.

Underpinning the cinematography, however, was this core idea of gravity. One of the hero lyrics is; “you are the ocean… and the moon that controls it”, so it felt natural for the camera to be pushed and pulled by the gravitational force of the lovers’ growing connection.

Wallis mentioned two things that stood out during our Skype chats; that she and Tracey loved to dance together in their kitchen – and that a gift-giving ‘to and fro’ ritual was unique to their relationship. One would gift the other with a small loving gesture, like a simple back rub – and the next day, it would be reciprocated in some form, like brekkie in bed. I loved this! Reminded me of the ebb and flow of an ocean tide. So it started to feel like the camera should ebb and flow, building in strength to a full orbital crescendo as the lovers’ connection grew.

How did you work with choreographer Yukino McHugh to map out the emotional journey your dancers would traverse and the interplay between the lovers’ emotions and that of the camera?

There were a few key steps.

Once I had a clear vision for how the story should play out on screen, I shared the first draft storyboard with Yukino who was in Tokyo at the time. We chatted over Skype together to get the ball rolling on development – and then beamed Wallis in from Berlin to chat more about her relationship with Tracey for further choreography inspiration.

One of the really cool things Wallis described were the little affectionate physical gestures she and Tracey shared privately. Gentle caressing up the forearm was one gesture, as seen in the opening sequence of The Ocean. Wallis pressing with her thumb into the space between Tracey’s eyes was another, designed to soothe her partner’s worries – again, seen later, at 02:04 in our film.

From there, Yukino’s brief was ultimately to translate my sketched (stick person) storyboard and vision into movement, ensuring it hit the five key planet ignitions in the extreme wide shots. These ignitions – where we see the planet-bubbles light up around the lovers – were placed at designated points in the narrative to indicate gear shifts in the relationship; the first ‘I like you!’ high five to the right; the synchronistic ‘getting together’ flow to the left; the heart-opening move upwards; the ‘we’re a team now’ burst upwards; and finally the 360 ‘letting go’ ignition where Tracey, played by Yukino, leaps into Wallis’s arms, played by Liv Kingston. In this way, I wanted to take the lovers from darkness to light; nothing to everything; disconnection to connection.

Two rehearsal sessions were booked in advance of the shoot day. It was amazing to watch Yukino and Liv work through the storyboard, along with the emotion of the song, and build the dance from scratch. They would try a sequence, we would then huddle, discuss, adjust if needed, refine – and repeat for each section. At the end of day one, myself and DoP Ash shot the first full draft of the dance on a 5D, experimenting with coverage, camera moves, angles, etc. as we went. We also used the iPhone to capture the slo-mo sequences.

That night, I took the rushes home and made a rough cut of the MV. This meant, that next day, we would be able to quickly see what was and wasn’t working – and refine choreography, start to finish.

Huddling back together for day two, we played this rough previs, threw away what wasn’t working, tweaked what was – and created new movement that worked better for the story. I refined the previs, ready for the final shotlist and shoot day.

Where there any surprises as to what was/wasn’t possible as compared to your initial plans?

The final shot where we track up the lovers’ bodies, then spin and track back to reveal the sea and sky of stars, was created on the fly on the shoot day. My storyboarded idea for the lovers’ position was completely different – featuring them sitting upright, facing each other – but the impromptu shot was so much stronger in the end. A really nice surprise.

Although not immediately obvious, VFX played a large roll in pulling off the orb ignition effects. How did on set preparations and post work combine to create this key visual expression of the lovers’ relationship?

It all started in pre-production, with a lot of VFX planning.

We quickly scratched the idea of capturing the orbs practically on the shoot day. To hang 100+ light bulbs from wires would have created a huge physical obstacle for the dancers, let alone a pain for the camera, limiting movement. Plus a potential nightmare to synchronise and execute the orb ‘ignitions’ in time with the performance.

By adding the orbs in post, we’d have more wiggle room to play with their placement in the scene and nail the best design and behaviour. Decision made. To cast light onto the bodies, we decided the best approach would be to manually dim up large lights – positioned out of frame to the left, right and above – upon the five ignitions on shoot day and then remove in post.

The addition of tracking markers in studio was crucial for adding the orbs in post; a task to research and plan correctly. Non-negotiables: they couldn’t spill light onto our dancers’ bodies, create flicker in camera or injure feet. We tested various small LEDs by filming offspeed in darkness. Once we found the best fit, a batch was ordered. In the meantime, we designed and produced mini silicon ‘ramps’ to fit around each of the tracking markers, so the dancers’ feet would be protected and light-spill minimised.

Shoot done – onto post!

To calculate the exact number and placement of orbs we’d need for all five ignitions, I first took screengrabs of our cleaned-up online edit (the extreme wides only) and added 2D orbs on top in Photoshop, starting with the final shot and working back. We only had two weeks assigned to complete all VFX at FINCH. The job realistically required a lot more time for all shots, so there was zero room for error. We had to work fast and think on our feet for a smart workflow solution. Precision of orb placement was key to kick off.

When done, Flame artist Jonathan took my Photoshop files and popped them into Flame to start sketching out their placement. He then tracked each shot (of the dance) using the tracking markers as reference, ready to comp the orbs into every single shot in between the five extreme wide ‘ignition’ shots. Meanwhile, 3D artist James worked in Maya to build the universe in 3D, create the orbs themselves and work out how to create smooth ignitions.

Re: the orb design, I wanted them to appear light and delicate, like ‘planet bubbles’ – resulting in a universe/ocean mashup feel. Having explored loads of different visual executions – hanging orbs versus magically floating orbs / solid versus translucent/interior flame versus interior glow – I decided upon a lightweight hovering ‘sphere within a sphere’ solution, allowing for new love (small sphere) to be ignited within a guardian-esque outer bubble (large sphere).

Next question: the surface material (shader). Frosted glass? Seaglass? Surface of the moon?

The final decision for surface material came from asking myself “What’s the ultimate metaphor for The Feminine – the birthplace of all potential new life and love?” Answer: the ovum. Final material for our orbs was comprised of a solid spherical centre encased within a thin, clear-blue outer glass.

Wallis and I wanted to make The Ocean, in part, as a gift for our younger selves who struggled with our sexuality growing up.

Given your aims for and thought out intentions behind The Ocean, what would you like audiences to take away from the film regardless of their sexual orientation?

That fear of intimacy (or sexual orientation) can close us off to experiencing real love and connection. But if the other person is pledging a safe space and you trust that to be true in their behaviour, it’s worth the leap of faith.

Are you working on anything new at the moment?

We just shot a new music video in Ireland which I’m really excited about. The same core dream team as The Ocean; DoP Ash and Flame artist Jonathan. I also got to work with the incredible Steve Wall – star of The Vikings, upcoming Ridley Scott series Raised by Wolves and new Chet Baker feature My Foolish Heart. He’s absolutely amazing to watch in action on set, a huge honour to direct. Other than that, I’m working on documentary series The Love Experiment that recently won silver at MIPFormats in Cannes; a mini musical; a couple of short docs; and always writing treatments for commercials, brand films and music videos.

You can catch The Ocean on the big screen at the Underwire Festival on Saturday 21st September as part of the Bodies in Motion programme.