The story of Sult (Hunger) still resonates today. First released in 1890, Knut Hamsun’s classic novel of an impoverished writer trying to find his way in Oslo possesses a remarkably modern insight into psychology and the human condition. Now it’s the subject of a short, abstract adaptation by Director Kenneth Karlstad – who as coincidence would have it last appeared on our pages with his suburban gothic tale of crime and masculinity entitled The Hunger (Gutten er sulten). Having studied Sult at university, I finally found a use for my English literature degree and called Karlstad to talk all about Norwegian literature and the process of adaptation.

What draws you to the work of Knut Hamsun?

It’s definitely the troubled and inconsistent main characters. That really inspired me when writing on my own; sometimes they just don’t make any sense. In all their chaos they make sense as well, and you never expect what you get from his characters. They’re very surprising in their manners and in the directions they take. That really struck me when I started reading Hamsun. I read Mysteries, Sult and Pan. Then I read some other writings of his as he went on a literature tour around Norway holding seminars. He’s very troubled and inconsistent in himself.

I liked the first part of his work because it’s more anarchist. He went from being an anarchist to being a Nazi so he was an extreme figure and that’s what I feel compelled to when it comes to him and his characters: there’s a lot of emotions and a lot of intelligence.

So how did the idea for the film come about?

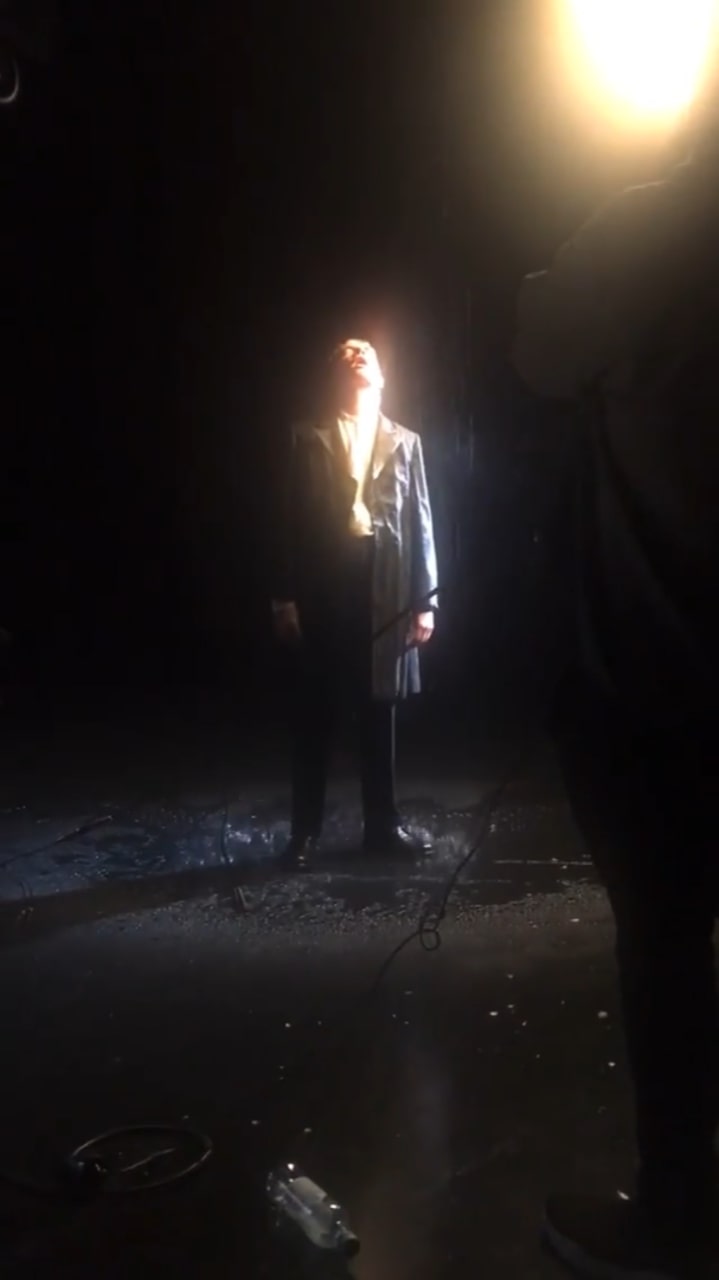

The film was actually part of a play – the images were meant to be running in the background. Then I decided I wanted to use the material for a short film. We shot in the theatre where it premiered. As it’s a play we had a lot of stuff that we could play with. I took extra shots here and there so that the film would work.

It’s an interesting approach to adaptation. It distills the key ideas into an experiential, music video-like mode. Why did you want to take the play and turn it into this short, snappy bringing out of its key themes?

It screened at the Norwegian Short Film Festival. One critic called it almost like a teaser or a trailer for Sult. I was a bit pissed. I didn’t want it to be a teaser, I wanted it to be something on its own. That’s why I tried to push the language of the images and to cut it up and experiment with the form. I was very inspired by Peter Tscherkassky: he makes short films where he takes old material and cuts it up and redefines scenes.

Yes, I have seen the film where he cuts up a horror with Barbara Hershey!

Yeah, it’s called Outer Space. I was really inspired by him. Not that I did his method at all, but I was inspired by the aesthetics of this snappy and very cut up style, like he almost tears the images apart and redefines the whole thing. I felt like that kind of style matched the inconsistent main character of Sult.

I didn’t want it to be a teaser, I wanted it to be something on its own.

And how did you pick certain passages from the book that you wanted to put in?

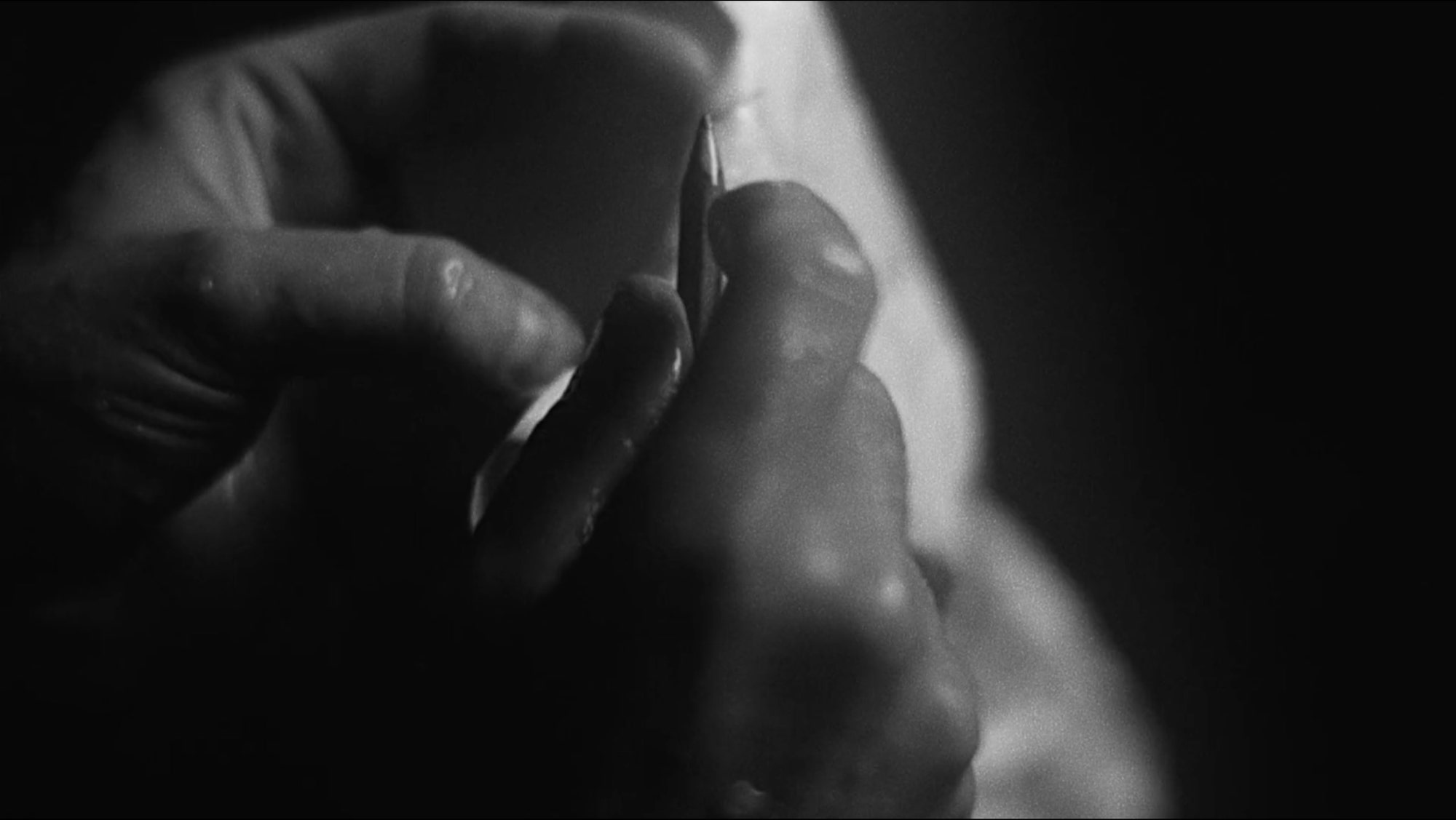

It was a very pragmatic thing. I always edit myself. I just picked out the images I liked the most and started playing around with them making sequences. Luckily the images I was most satisfied with were the ones that could tell a pretty short story of this book when it comes to his inner chaos, meeting Ylajali and then leaving Oslo. I locked the edit first, then I found passages from the book that could work with the images and kind of worked with the story and had an end. Having an ending was the most important thing.

There is a three-act structure: it starts quiet, then goes loud, then quiet again. How did you want to create this sense of pace and chaos, and how quickly it can spiral out of control?

I wanted to catch the poetry of Sult. Even though the book has a fast pace and is very chaotic in its form, it’s also very romantic. I wanted to have that aspect as well and then just cut it up and to get the audience to feel the inner chaos that he feels. Then maybe to have some hope in there as well with Ylajali. I was trying to make it not only dark but also romantic.

The films starts with these abstract-looking faces, which are stretched and feel like they’re dissolving. How did you achieve that effect?

Though a flexible mirror shot. We had actors sit on a chair, then we had this flexible mirror in front of them. The actors actually held this 1 x 1 mirror themselves. We would just experiment with that. It was funny to work with that mirror because a lot of the material we have is just so weird, almost too weird for the film. The ones that we’re using are the more subtle ones actually. But it kind of made sense because the character is very shattered.

And this sense of madness is stressed by the techno music. Why did you pick it?

I’m very into techno but I tried not to use a track that’s too rave-y. Instead, I picked something that was more fun to edit images to, as it has so many things to play with. I’m a techno geek and I make some music myself so I found it through my hobby. Additionally, my style is a bit inspired by techno visuals.

I was very inspired by Peter Tscherkassky: he makes short films where he takes old material and cuts it up and redefines scenes.

Coming back to the task of adaptation: what’s it like taking on someone who is such a seminal figure in Norwegian literature?

The only thing I was thinking about was that I shouldn’t put Hamsun on a pedestal. I read a lot about how Hamsun attacked his inspirations. He was really nasty to Henrik Ibsen, even though he admired him, and criticised him in front of his face by saying that his characters were one-dimensional. He was an anarchist at the time. I also tried to think “Fuck Hamsun” and to make something on my own.

How do you square making a film based on someone who would later support the Nazi party?

I think that question is very relative. You can’t think black and white when it comes to that kind of question. Sult was written in his anarchist period, so he was an extreme leftist when he wrote it. I find it wrong to think of it as the work of a Nazi. Here I can find a good excuse to celebrate his work; as long as it doesn’t preach anything hateful I think it’s OK.

What are you working on next?

We just got in development for a TV series. It’s called Kids and Crime. It’s based on the true story of fifteen to twenty year olds in my hometown from around the early 2000s. They’re a group of friends that did a lot of small time criminal stuff like selling drugs and robbing houses. It has a Trainspotting-vibe to it. Fun but dark.