There’s a real sense of mysterious allure to Bradley Tangonan’s short film River of Small Gods. It follows Anela, a displaced native of Hawai’i, as she is approached by an enigmatic sculptor who asks her to fetch precious lava stones for a surprisingly large fee. Tangonan’s mythic drama, at its core, is about our connection to heritage and the consequences of trying to deny its influence on who we fundamentally are. DN caught up with Tangonan as River of Small Gods continues its film festival run to discuss the personal inspiration behind his short, the importance of working with a local crew, and the responsibility we all share to tell the stories of the marginalised.

There’s a real sense of magical realism to the narrative of River of Small Gods, how did the story come about?

This story began with the creation of the character. Anela is a Native Hawaiian construction worker with an injury that prevents her from working and she embodies many of the conflicts inherent in surviving in Hawai’i. How does everyday survival interfere with social and spiritual well-being? How does displacement sever our connection to the land where we were born or where one’s ancestors were once stewards? These questions were the seed for the story. I saw the possibility of creating a modern myth that uses allegory as a bridge between the present and the past. In this way the visceral reality of the main character; her body, her injury, the roof over her head, the heavy stones she is hired to carry and collect, segue into the emotional and spiritual reality underneath the physical.

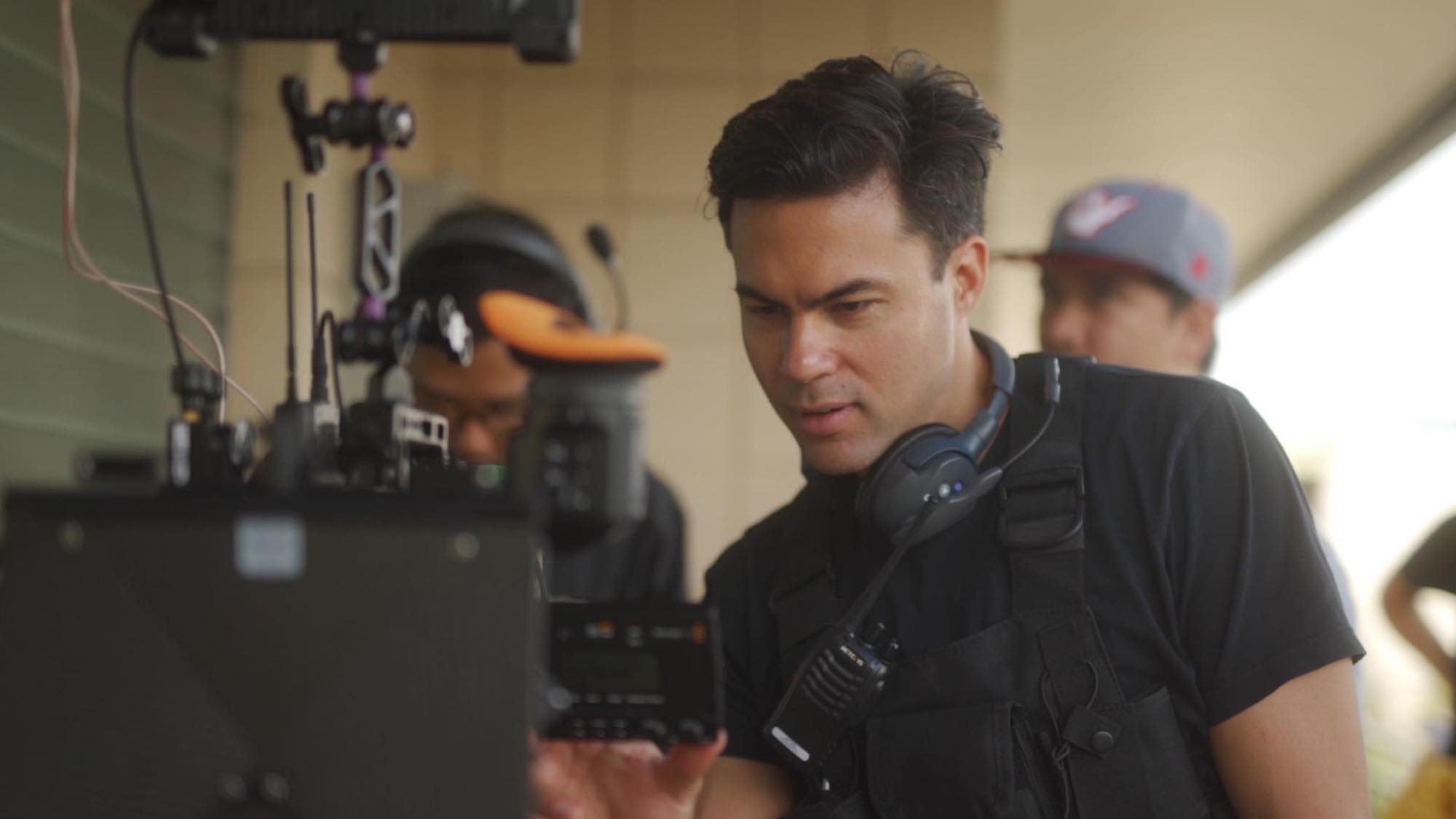

When it came to shooting in Hawai’i, did you bring in previous collaborators that you had worked with before or did you utilise a locally sourced crew?

It was very important for me to work with local and Native Hawaiian cast and crew members. The vast majority of the images of Hawaiʻi that are presented to the world are captured by people who are not from Hawai’i, who are not Native. These films perpetuate the tourist’s gaze because they are told by tourists. Native Hawaiian people are typically relegated to side characters, extras, or omitted from Hawai’i-based stories entirely. As a non-Native, local-born storyteller, it’s my responsibility to create stories that uplift and centre the stories of those marginalised in my home.

Now that you’ve finished the film, what was your experience like working with that crew to tell the story of Anela?

This was a very grassroots and micro-budget film. Everyone came together to stretch every resource we had to build this world and tell Anela’s story. I’m incredibly grateful to have worked with people so dedicated to the story and willing to adapt to challenging and unforeseen circumstances. For example, a storm flooded the riverbed where the third act takes place and the crew was willing to wait until the waters receded to shoot on a later date.

I saw the possibility of creating a modern myth that uses allegory as a bridge between the present and the past.

Amazing! What did you shoot River of Small Gods on? Visually there’s a real blend of myth and realism.

We shot on the Blackmagic cinema cameras which are much more affordable than the Arri cameras most films are shot on. The DP Micahel Tanji and I used my set of Leica R vintage still lenses along with Smoque filters to capture the kinds of images we felt could render the blend of verité and allegory that the story moves between.

How has it been bringing this project together? Given the requirements for shooting and gathering a local crew it must’ve been an extensive feat to pull off on a low budget.

It took me a year to concept, write, and revise the story along with the help of screenwriters Aaron and Jordan Kandell. We shot the film over the course of a week and a half in early 2020. The pandemic put post-production on pause for a long time but that time away from the story helped to give perspective on the edit that a rushed post-production would not have allowed. Colourist Nat Jencks from Technicolor PostWorks and the sound design team One Thousand Birds finished colour and sound at the beginning of 2021.

A lot of the film takes place in fairly rural locations, what were the challenges of shooting in these parts of Hawai’i?

It can be really challenging shooting in remote locations. The benefit is that when you are working together far away from the nearest town, you have the opportunity to become attuned to the surroundings. At one point we were clearing a corner of a cave in order to film the penultimate scene in the film and the cinematographer turned to me and observed that I had just tossed a large rock fragment across the cave floor. In a very gentle way, he was asking me to respect the natural place we were shooting in in the same way that the film asks the audience to be mindful of every stone or branch or root you come across in the world.

Have you managed to show the film to many Hawai’i locals? Is it important to you that they feel River of Small Gods is a fair representation?

From the birth of the story through the final cut I’ve worked with kamaʻāina (Hawaiʻi-born) and Kanaka (Native Hawaiian) collaborators and contributors to craft a film that represents both the people and the land in a meaningful and realistic way. In particular, it was important to me that the character of Caleb, the artist who hires Anela to take stones from the river, be a local character rather than a character who is haole (an outsider). Alienation from the land runs so deep that everyone in Hawaiʻi, including those born there, may not be aware that they are perpetuating harm against it and the people who would be its stewards.

As a non-Native, local-born storyteller, it’s my responsibility to create stories that uplift and centre the stories of those marginalised in my home.

What’re you working on next?

I’m in the early writing stages for a few ideas, but I would love to tell more stories based in Hawai’i centering on and made by kamaʻāina and Kanaka people. One exciting thing I’m hoping to do is an installation piece consisting of projections of various natural spaces on Oʻahu in which visitors can only go into the viewing space after asking the space itself for permission to enter.

Hi Bradley, Very haunting and inviting intro. We want to know more. Your title intrigues me because for 37 years U have lived in a 1927 house built on boulders that go right into a stream. The rocks have protected the house for nearly 100 years from the many floods that happen. The biggest flood ever was in 2016 from the remains of Tropical Storm (ex-Hurricane) Darby. The stream rose over 12′ and when the water receded, there was a new, large boulder in the center of the stream opposite my property. I think of it as a gift and welcomed it. You may enjoy a visit.

Aloha, Rick (from the Hallmark movies, Set Dec)