After losing his vision at age 25 due to a condition called retinitis pigmentosa, skateboarder Justin Bishop gave up his passion. Three years later, he set out to learn it again. Documentarian Leo Pfeifer (who we last featured for his contemplative short doc Lost Time) captures Bishop’s reflections upon this challenging period of his life with his latest film One Day You’ll Go Blind. It covers Bishop’s journey back to the ramp after years away, digging deep into what drives him to move forward. It’s a beautiful and humanistic documentary that Pfeifer captures fluidly, letting his Bishop and his ruminations drive the narrative to its optimistic finale. DN was happy to join Pfeifer in conversation once more to discuss his method of documentary filmmaking, the impulse he felt to tell Justin’s story, and the compelling impact the film has had thus far.

Where did you come across Justin’s story and what drew you to reach out to him?

This film’s origins were totally organic. I came across Justin’s story in an article for Thrasher Magazine and I couldn’t stop myself from a YouTube deep-dive on him. His athleticism was the initial hook, but I could tell there was an inner journey below it all that could be told beautifully in a documentary. I sent him a message and we got on a call right away, which lasted a few hours. Justin was open with me and I just felt a great spirit there in his desire to share his story, not for himself, but for the impact it could have on other people. From there, I went to my friends Andres and Loucas at Alto Visuals and pitched them on the doc. They signed on as executive producers and we all set out together to bring the film to life.

His athleticism was the initial hook, but I could tell there was an inner journey below it all that could be told beautifully in a documentary.

What is your general process for approaching the subject of your films and how much do you leave open for when production begins?

My process involves a lot of conversations with my film’s subjects, delving into their story, who they are, and the experiences they’ve had in life. From that foundation, I map out the film on a very deep level, while also knowing that docs are all about the unexpected truth of real life, parts of the plan will inevitably go out the window during production, and the film will be better for it. Some shots and sequences materialized in the film exactly as I imagined and some emerged entirely as we shot. Most are some combination of the two.

How did you prep with Justin for the shoot and get him comfortable in front of the camera?

A couple weeks before we shot, I drove to Vegas and spent some time with Justin and his wife Carol. We got drinks, and the next day I stopped by his house to scout, and meet their three lovely dogs. I think it’s so important to spend time with your subjects before shooting and connect on a human level. I’m asking Justin to be tremendously vulnerable on camera, and the least I can do is open up about myself and be vulnerable with him. Bringing a camera crew into someone’s life is one of the most unnatural things you can do, so one of my big jobs on a shoot like this is helping everyone reconnect to that sense of normalcy.

How long did you shoot for in total?

With a small but mighty crew, we shot for three days at the end of January 2021 on Alexa Mini with Kowa anamorphic lenses.

What was your goal, aesthetically?

Aesthetically, the goal was capturing real, authentic, and naturalistic moments with an immersive cinematic flair, interweaving beautiful verité with dramatically-realized precise imagery. If the audience can almost forget they’re watching a doc then we’ve succeeded.

Knowing the heart of the story and honing into my subject’s emotional journey is key, everything during prep and production runs through that lens. To me, docs aren’t about becoming an invisible fly on the wall, but rather collaborating with my subjects to capture something that elevates their emotional truth. I’ve found this to be much more powerful in evoking empathy with an audience. Everything in the film is true and accurate, but our visual language is written in prose, not just a ‘document’ of life.

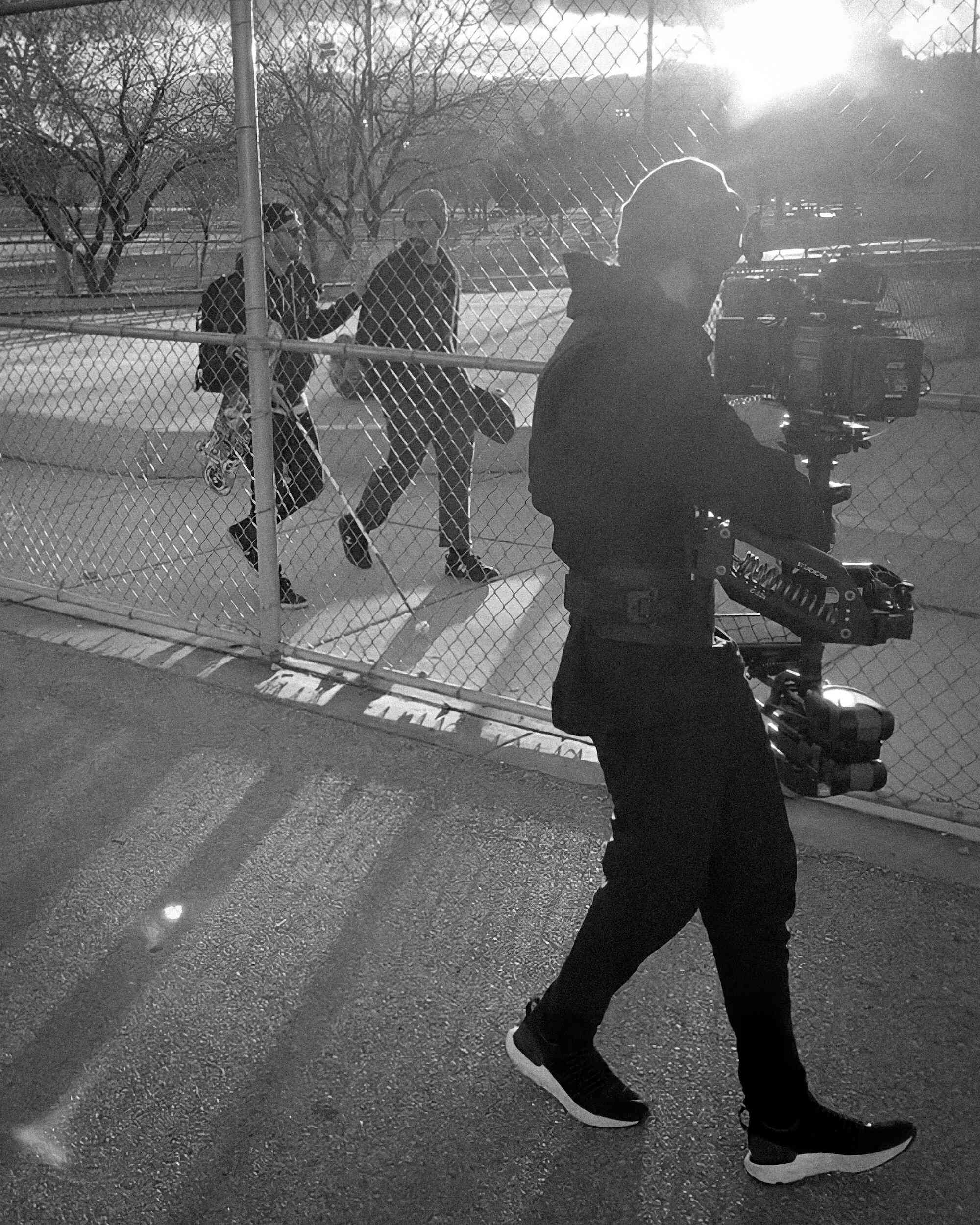

I noticed that you utilised a lot of Steadicam footage too which allowed you to capture Justin’s movements on and off his skateboard in that same natural yet fluid way.

Steadicam is one of the heaviest, most delicate, and challenging pieces of equipment to take off a traditional film set and bring into the real world yet that was key to realizing the vision of this piece because it allows moments to unfold dynamically without the need for a cut.

The film starts with a minute-long shot that spans from extreme wide to close, and back again. Dylan Burzinski, our Steadi op, was running up and down skate ramps and using his own experience with skateboarding to sense Justin’s rhythm. Before we shot, I had a long conversation with Dylan about our process, I would be in his ear via walkie giving direction as I looked at a monitor, but his instinctual moment-to-moment decisions were also vital. When you’re filming real people without pre-planned movement, the op has to react intuitively in that moment. By the time I could give him direction, the magic would have already passed. Dylan was incredible at this, not just bringing his technical skills, but crafting movement informed by our story.

How did you approach production on the direct interview section of the doc?

At the end of our second day, we shot the interview. I always aim to create intimacy in my interview shots, so my DP Kevin Pontrelli was hand-holding the camera about two feet away from Justin, and I sat at the same distance. We went deep on Justin’s story, his love for skating, and his hopes for the future. And, inevitably, some moments got emotional.

If the audience can almost forget they’re watching a doc then we’ve succeeded.

As Justin told me the story of going blind over three days, he broke down crying. So did I, and as I glanced around the room, I realized the whole crew had joined us. Those kinds of moments always remind me of the responsibility you have as a filmmaker, to tell your subject’s story faithfully, and bring to life a film that honours their commitment. Justin gave a tremendous amount of himself to make this film. He had to trust me as a storyteller, and at times, had to immerse himself in some really painful memories. That’s something I can never repay, and I’m eternally grateful to him.

It’s a doc that’s travelled far and wide too. What impact have you noticed from releasing it out into the world?

Since we filmed the doc, Justin has placed in the Dew Tour, appeared in a commercial narrated by LeBron James, and helped steer skateboarding’s admission to the Paralympics (the 2021 Tokyo games were skateboarding’s debut in the Olympics). I hope releasing this now can help elevate Justin’s message even further while exploring his emotional journey in a way that hasn’t been seen yet.

At the end of the day, I think there’s a tremendous amount to learn from Justin’s story. Whether you interpret it as a testament to overcoming one’s disability or a more general story about our power as humans to prevail against life’s obstacles, everyone will have their own takeaway. As a filmmaker, all I can hope is that I’ve authentically conveyed a real person’s story, and crafted a film that brings a little more empathy to the world. As Errol Morris said, “I think calling someone a character is a compliment.”

Can we expect another documentary from you soon?

At the moment, I’m making the jump more into the world of commercial and branded directing, pitching on some great projects as I translate my doc passion to that medium. On the passion project side, I’m gearing up to release my YDA shortlisted doc about hip hop as a form of therapy in The Bronx, and prepping to shoot a three minute sports piece about a football player with a really incredible story.