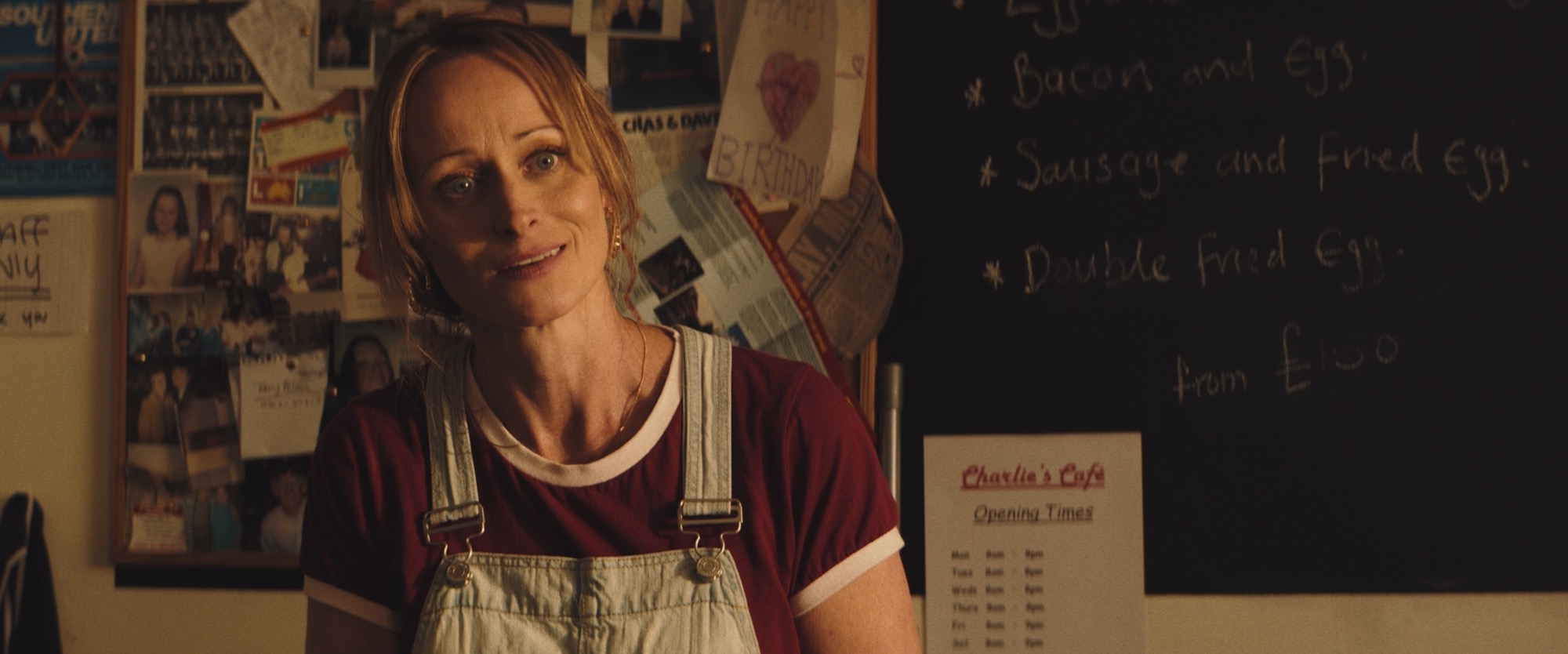

A greasy spoon cafe, filled with the usual markers of somewhere you know you will get a good cuppa and fry up, is the stage for Director Paul Holbrook’s enigmatic short Old Windows – a film which we highlighted as a standout of last year’s The Shortest Nights’ programme. Holbrook worked meticulously with co-writer Laura Bayston, who also co-produced and stars, to create an incredibly tightly scripted piece of work where every question, answer and gesture is carefully thought out and layered with nuanced additional meaning. A seemingly mundane interaction between a cafe owner and a customer, deftly played with a worrying hint of menace by Larry Lamb, brims with subverted meaning and undefinable weight making it a captivating and active watch we couldn’t take our eyes off for fear of missing even the slightest detail. Old Windows bathes you in the orange hues of golden hour which serve to balance the building tension and sense of dread growing in the cafe. Ahead of the film’s premiere on Directors Notes today, we took some time with Holbrook to discuss the challenges presented by directing such a dialogue-driven project dense with meaning, the incredibly detailed approach they took to character development and creating a setting for the film which spoke to the years of lives lived within its walls.

This is the fifth collaboration between yourself and Laura Bayston, what did the development process for Old Windows look like and how does your established relationship enrich the work you make together?

I’ve been working with Laura now for several years, and I hope to for many years to come. We just so often find ourselves on the same page tonally and emotionally. We have similar working-class backgrounds, and we are both drawn to character-driven, grounded stories and have fun unpeeling the layers from the broken characters we create. Our tastes are perfectly aligned too. We also ask each other the difficult questions and pull apart and interrogate every project we work on together too, so it’s always a mutual search for the underlying truth in everything we do. Thematically, the same stuff seems to be bubbling away in us both, so our sessions can sometimes feel very cathartic too.

This story lived through the two complex characters and not any flash and flair.

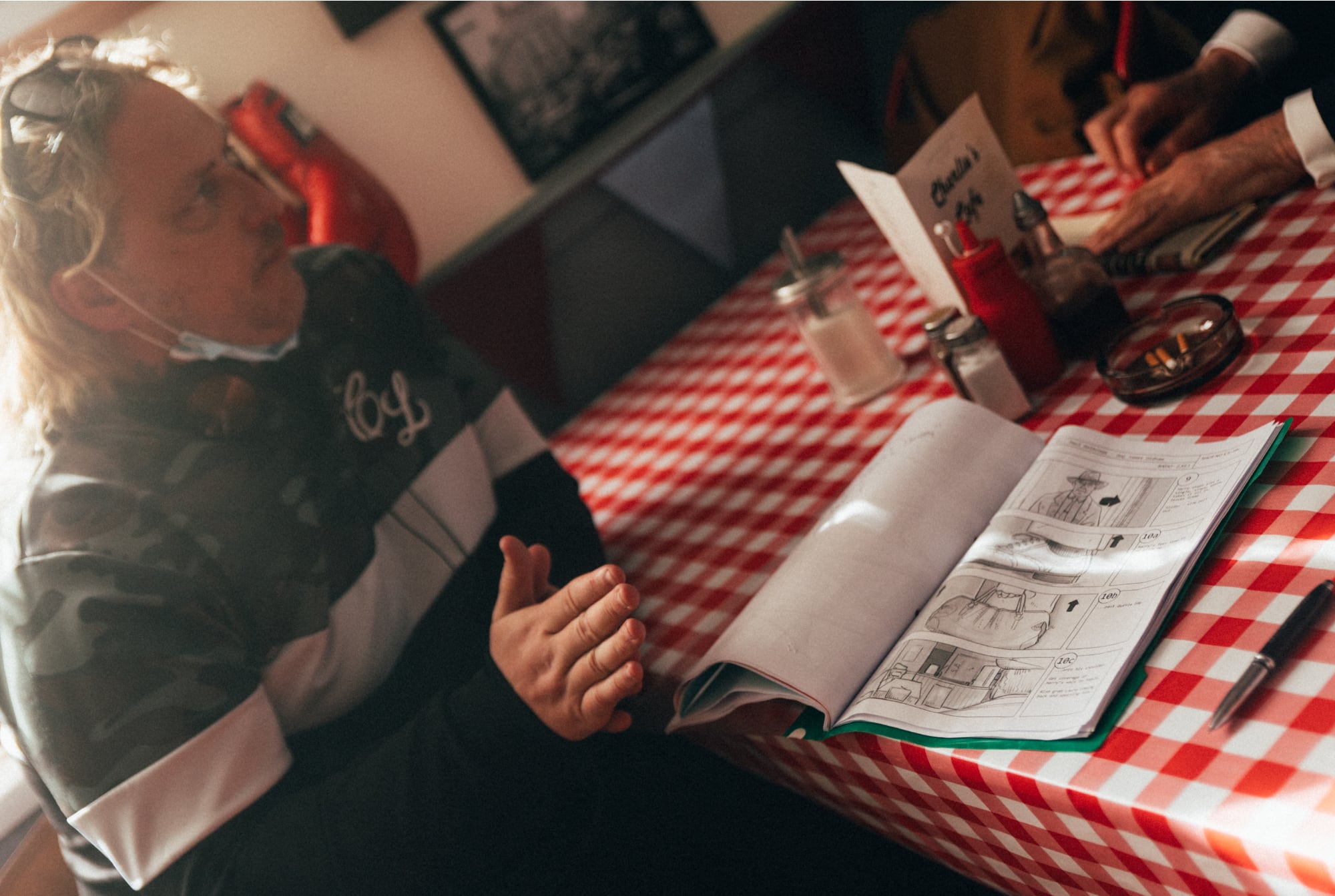

Laura came to me with the bare bones of a script about a year prior to us shooting it. The first thing that jumped out to me was the sense of place, history, family and nostalgia that flowed through it, and just how much of the story happened beneath all of this, so much unsaid. I recognised my own family history in her writing and related to this undercurrent of longing for a time gone by. It also struck me that it would be a relatively cheap film to shoot being a two hander in just the one location. I had been looking for a project of this kind for a while, recognising that the majority of my work previous to Old Windows were very quiet films, often stripped of dialogue – this was a proper talkie and I relished the challenge of moulding the subtext of this story alongside Laura, as well as working with limited visual tools from a filmmaking POV. This story lived through the two complex characters, and not any flash and flair.

Once we had the structure of Laura’s story locked down, we would meet once a week to work on the back stories of the characters and their family units, cultures, generational histories and then weave as much as that as we could into the subtext of the piece. We were always mining for hidden depth. The story remained pretty tight throughout from a structural point of view, so the majority of our redrafts were often focused on what was unsaid, or what we could remove dialogue-wise and replace with subtext. We would constantly challenge ourselves to be removing stuff, more so than asking ourselves what was missing. We knew everything about our characters, and their respective worlds, so what was said in that room between them both was always loaded with that knowledge. A reoccurring challenge for us was how much we could trust that the subtext would load things up for the audience, versus us taking too much away and leaving the audience confused or short changed. I think we got that balance just right, with time.

How, in the writing, did you construct that growing feeling of unease and focus on the subtext whilst still keeping an overtly casual conversation?

We almost wrote two scripts, one spoken and one unspoken. The historic, generational, culturally rich backstory in this piece was hugely important, I wanted to ensure there was always an undercurrent of mild threat yes, but for there to also be layers beneath the surface story that the audience would have to really concentrate on to get the full picture. I was wary of the simple set up, two people talking becoming boring, so I wanted to ensure the audience remained engaged, almost creating their own little backstories for the characters, and having to really lean in to fully grasp the dynamics.

It worked too, every time I watch the film with an audience, you can feel that sense of everyone leaning in, trying to decipher what is going on in that layer beneath the dialogue. The enquiring nature of the audience had to be replicated by the two characters too, both listening, learning and leaning into each other’s back stories to try and work out who they really are, and how this meeting is going to unfold.

The actors needed to fully understand and get on board with the fact that they were actually playing two characters each.

The performances from both Bayston and Lamb are phenomenal and add significant layers onto the nuanced writing, was it all scripted and how did you build those performances?

Yes, everything was scripted, right down to subtle eye movements. Once the game was afoot, it was a case of reminding the actors what is known, what isn’t, and what they want to know, all the while both putting on an act of sorts, masking their own insecurities and future outlooks. The actors needed to fully understand and get on board with the fact that they were actually playing two characters each, the one being put out into the world and the one desperate to break out from within, and this was always the internal conflict we wanted to play with, eventually finding a middle ground between both that hopefully leaves both questions and answers as to what the future may hold for both of them.

The cafe’s detailed mise-en-scene plays its own role in the film, tell me about finding that location and dressing it to match the richness of their multi-layered conversation?

We wanted to shoot in Bristol, despite the film being set in London (knowing we had access to our usual crew down here) so we set out to find the old school café in the script. Nothing locally was quite floating our boat, so instead we found a café that was a completely blank canvas and set our design team the task of transforming it into what you see on screen, and they really did do a fantastic job, it was a complete transformation and when myself and Laura first saw their work, we were instantly transported to the location we had long envisioned in the script.

It was all about generational nostalgia, not purely for a time gone by; family, lost dreams, etc. I wanted the walls to tell their own stories, stories throughout time that still retained a sense of who Kerrie is. She is a proud working-class business owner, she may have had to park dreams of her own to keep the family business going, but I wanted the space to belong to her own sense of positivity in the face of that, whilst still retaining that warm, nostalgia of a large family unit, a history of both good times and bad. The café had to give us that unique sense of place, a place that both Harry and Kerrie feel comfortable and safe in, a middle ground that would work as a crossroad between the past and the future.

I love the orange hues and soft lighting. How did you approach the cinematography and overall tone of the film?

The orange hues were always in the plan to help us create the feeling of nostalgia, as were the colour choices in design and costume. Our Director of Photography James Oldham also took on the role of colour grader, so the grade was an ongoing conversation throughout the shoot. In post there was lots of back and forth to find that fine balance between the on-the-nose sepia look and something more akin to the colours we had designed into the location. Some of our first passes at the grade, although beautiful, were too overbearing and distracting, but once that balance was found, it really added another layer to the tone of the film. For James, the balance of saturation and colour was crucial to be able to play around in the sepia ballpark, whilst still having all our colours in the scene come through nicely.

We wanted the grade to help with the feeling of nostalgia, but the colour had to play ball with the tone of the film, it’s not all about looking back, and sometimes the sepia look can feel a little too melancholy, but luckily the grade turned out exactly as I imagined. Communicating what I’m looking for, whilst trying to not contradict myself is always difficult, I want sepia, but not sepia for example…but luckily James is a very patient person, and a great listener; he is also a creative technician and was always locked into what we were trying to achieve very early on.

I wanted the walls to tell their own stories, stories throughout time that still retained a sense of who Kerrie is.

There are some stunning close ups which really draw us into the intimacy of the story, what was your camera and lighting set up for the shoot?

We were extremely restricted with our budget on this film shot over two days with a £10k budget, our kit was provided (again on the cheap) by No Drama, Tracks and Layers, Visual Impact and Cinewest as well as lights and grip from crew member Jon Head (Grip) and Michael Sides (Gaffer). We combined the URSA 12k with Orion Anamorphics to try and create a softer look. The close ups were generally 40mm and due to the size of the room, we stayed on this lens pretty exclusively throughout the film. With the lighting, James used two T2s for the sunlight coming through the windows, and a Gemini 2×1 inside the location to key or add an edge. His approach is always to keep things as simple and pragmatic as possible, to give the actors a beautiful canvas to perform in.

Are you planning to continue focussing on more dialogue driven films moving forward?

I have three higher budget short films that are in the mix to hopefully be my last before moving into TV and features. It’s a case of trying to find funding for them; we have our eye on the new BFI/Film 4 film fund. When She Sings is psychological horror/drama about a tired creative growing up in an oppressive small town and mermaids. This is another collaboration with Laura and is being produced by Andrew Oldbury (Oscar’s Bell). White Sheet is a drama about two vengeful octogenarian veterans struggling to get by in broken Britain, which is being produced by Buffalo Dragon. The Saturday After is about working-class fatherhood which is being exec produced by Slick Films.

Beyond that I have a TV comedy in development with Sky called Joan of Park, three drama features optioned (Hungry Joe [watch the original short film here], Wolves & Snog) and a fledgling TV production company called Bristol AF which is where I park TV comedy ideas outside of my drive towards my debut feature.