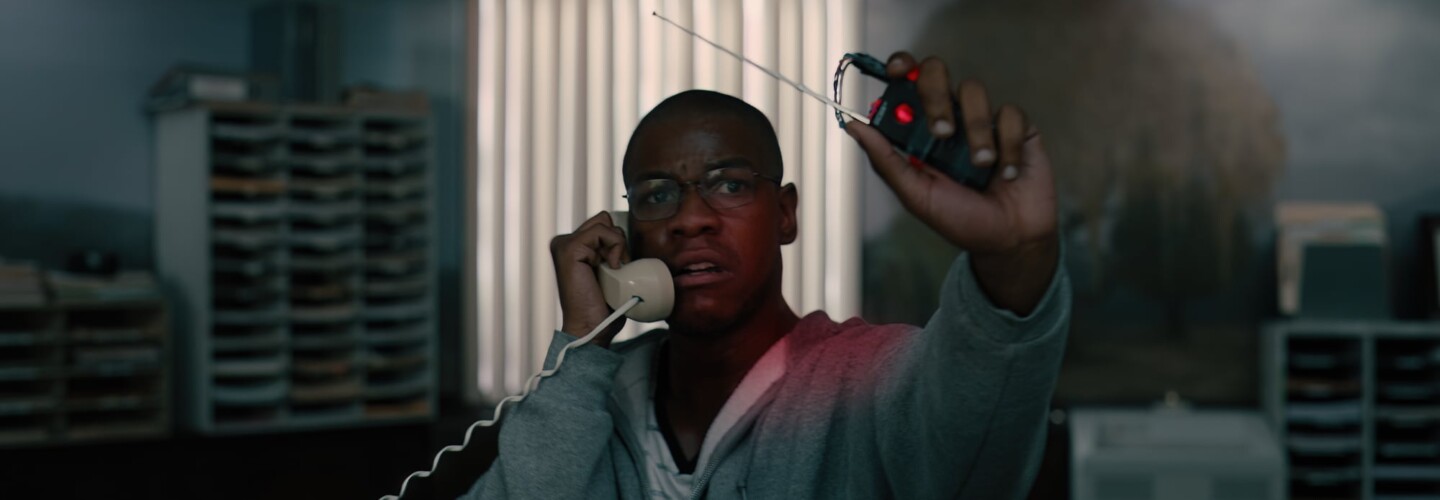

Bank robberies are a staple of cinema. They usually go two ways. There’s the secretive, carefully planned out break-ins like in Rifiki or Ocean’s 11, or there’s the all-guns-blazing approach of Heat and Point Break. But when Brian Easley walked into Wells Fargo Bank in Atlanta, Georgia, in 2017, he took neither approach. An exceptionally mild-mannered man, he held up the bank with a homemade bomb in order to ransom the Veteran Affairs association for unpaid disability benefits. Honouring this story with a mixture of empathy and grace, as well as considerable dramatic flair, Abi Damaris Corbin’s Sundance Special Jury: Ensemble Cast award winning feature Breaking splits the difference between the two genres, providing a modern update of Dog Day Afternoon that incisively indicts a broken system. Ahead of the film’s digital release on March 27th, we talked to Corbin about working with both John Boyega and the late great Michael K. Williams, being inspired by the close-ups in Jonathan Demme’s oeuvre and mapping out the initial blocking with dolls in her home.

This is your debut feature! What was it like landing such a high-profile gig with your first film?

I find that as a first-time time director, nobody gives you a high-profile project. You have to create one. You have to build something from the ground up. And this story moved me on a deep level. I partnered with Kwame Kwei-Armah to write it with me with some development producers from Epic and Salmira Productions. Then Ashley Levinson and Kevin Turen came on after we cast Jonathan Majors, initially, in the role, before some difficulties. Then the man we needed to be in the room, John Boyega, came into the room, and we were off to the races.

Your father was a veteran. I imagine this must have been a very personal story for you.

Very much so. My dad, during his time in the Navy, contracted Agent Orange, as so many veterans did during Vietnam. Time and time again he was denied benefits, as Agent Orange wasn’t even acknowledged by the veterans affairs department until more recently.

As a first-time time director, nobody gives you a high-profile project. You have to create one. You have to build something from the ground up.

Tell me about bringing in Kwame as a co-writer. Did you always want to have a co-writer on this project and tell me how it worked as a team.

For this project, I knew that to get to the truth of the story, it’s not something I would do alone. Brian Easley’s a man of colour, who lived a very unique experience in Atlanta. Kwame raised his children in Baltimore. He had some things to say in this story that Brian had to say. With the pairing of the two of us, as well as with Brian’s wife, at the table, we could get to the truth of the story. I have an amazing respect for how Kwame has chosen to be as an artist, with such integrity and with such an ethical nature. He really strives to make the world more pure and true with his art.

It’s interesting you mentioned that the family was on board. Were they always willing to be part of telling Brian’s story?

I first read Brian’s story in the Task and Purpose article by Aaron Gell. There was an enormous amount of research that he had done. We already understood once reading the article and speaking with Aaron, that there was a desire for the story to be told by the family. Brian still hadn’t really been heard fully. Once Kwame and myself spoke with Aaron, we reached out to Jessica, because we knew that the desire was there. After speaking with her, we knew we could move forward.

For this project, I knew that to get to the truth of the story, it’s not something I would do alone.

As someone who has been following John Boyega since 2011 with Attack the Block, it’s great to see him taking a risk like this. What’s he like as an actor to work with, and how was it for him to nail the Atlanta accent?

John’s phenomenal to work with. He’s just a great human. He’s an artist through and through. He just knows his craft. Of course, he dug into the specificity with a dialect coach. He really studied Brian in the short span of time he had. His craft was there so he had the tools to be able to do so. As an EP he took ownership to make sure we were able to tell Brian’s story with integrity. To have the person who is number one on your call sheet turning up and going the extra mile is just an enormous gift as a director.

This was unfortunately Michael K. Williams’ last film. It’s so sad because you got a great sense that he had so much more to offer as an actor. What was it like to have, I don’t quite want to call him an elder statesman, but definitely a veteran actor on set?

Elder statesman’s a good role. He was a rock for all of us on set. When I sat down with him the first time, I had a really candid conversation with him and said: “Mike, it’s my first feature. I’m prepared. I’m ready to go. I’ve done my homework.” This is something we all do as directors, so we know what we need to communicate to our department heads. I said to him, “You’ve got an enormous amount of experience, and I want to make sure I honour that.” And he said: “You want to tell a story, you want to tell it right. I got your back.” And he did. Every day.

A lot of the film, especially the first half, is just in one location. How do you keep it fresh? Did you think a lot about how you would block the scenes? Were there a lot of rehearsals involved?

Of course. It was the thing that kept me up at night! We didn’t have the luxury of a lot of rehearsal time. One reason was the budget. The second reason was shooting at the height of Delta. You’ve really got to bubble people and you’ve got folks who are immunocompromised. So we had to get a little crafty. Firstly, I blocked things out with dolls on my own. Then I made it a lot better with my DP Doug Emmett, then we moved a lot of the furniture around the house to make it look like the bank. Then we called the production designer down at the bank to say, “Can you move the chair six feet to the left to see how that will do?”

The actors had the freedom to move within the space because we had a plan in place.

Then we watched a ton of films and then we did it again. After that, we came to a sense of like, okay, this is probably a good way to block the shape of the film. Then we made sure to have visual variety within that. We added a mural behind Brian so that could have lots of things to shoot. We added grasscloths to the wall. We made sure to progress the camera in where we were putting it. We moved Brian around the entirety of the bank. We did not have time to release all of that with our actors, but the AD did it with the DP once we got to the location. We would just rehearse it before the actors got there ad nauseam so the crew had the fluidity of knowing what was going to happen. The actors had the freedom to move within the space because we had a plan in place.

Another simple yet highly effective technique you use is through the close-up, which looks great on widescreen. Did you always want to use close-ups?

We looked a lot at Jonathan Demme’s close-ups, as well as the close-ups in Moonlight. But Demme is a master. You really feel like you’re invited into a character’s soul. But we used it with quite a bit of restraint. You’ll see the side profile, where he turns away from the camera so that as an audience member, you’re invited to put your own emotion on his face, as we’re withholding that. John just knows how to move with the camera. And that helps enormously.

I really do believe that film can be birthed from a place for freedom and processing and not purely from pain

Where the film feels different from classic heist movies is that it’s not really a heist at all. This is a man’s plea for recognition. What was it like trying to nail down the specifics of that human side?

It’s a warm and sincere-hearted rebellion against a broken system. There’s an enormous heaviness to try and capture that on set every day, knowing that it is a real man that you’re capturing. You really do have to put some things in place so that you can go home and walk away. I could never do that. But John had some really good tools in place to be able to distance himself from the character. We talked a lot about that, because historically in film, it’s about getting it done at all costs. But I really do believe that film can be birthed from a place for freedom and processing and not purely from pain. So seeing those tools be used by John had a really big effect on me as a creative. The art does not suffer to work from freedom. In fact, it blossoms in a beautiful way.

What are you working on next?

I’m writing. Hopefully directing a couple things coming up soon that will be announced… at the time they’re announced.

Would you like to work with John again?

I’d love to. It’s such a privilege to work with him. We deeply loved that process. Bringing Brian’s story to life was such an enormous privilege. It would have to be the right collaboration, but I’m sure we’ll find something down the line.