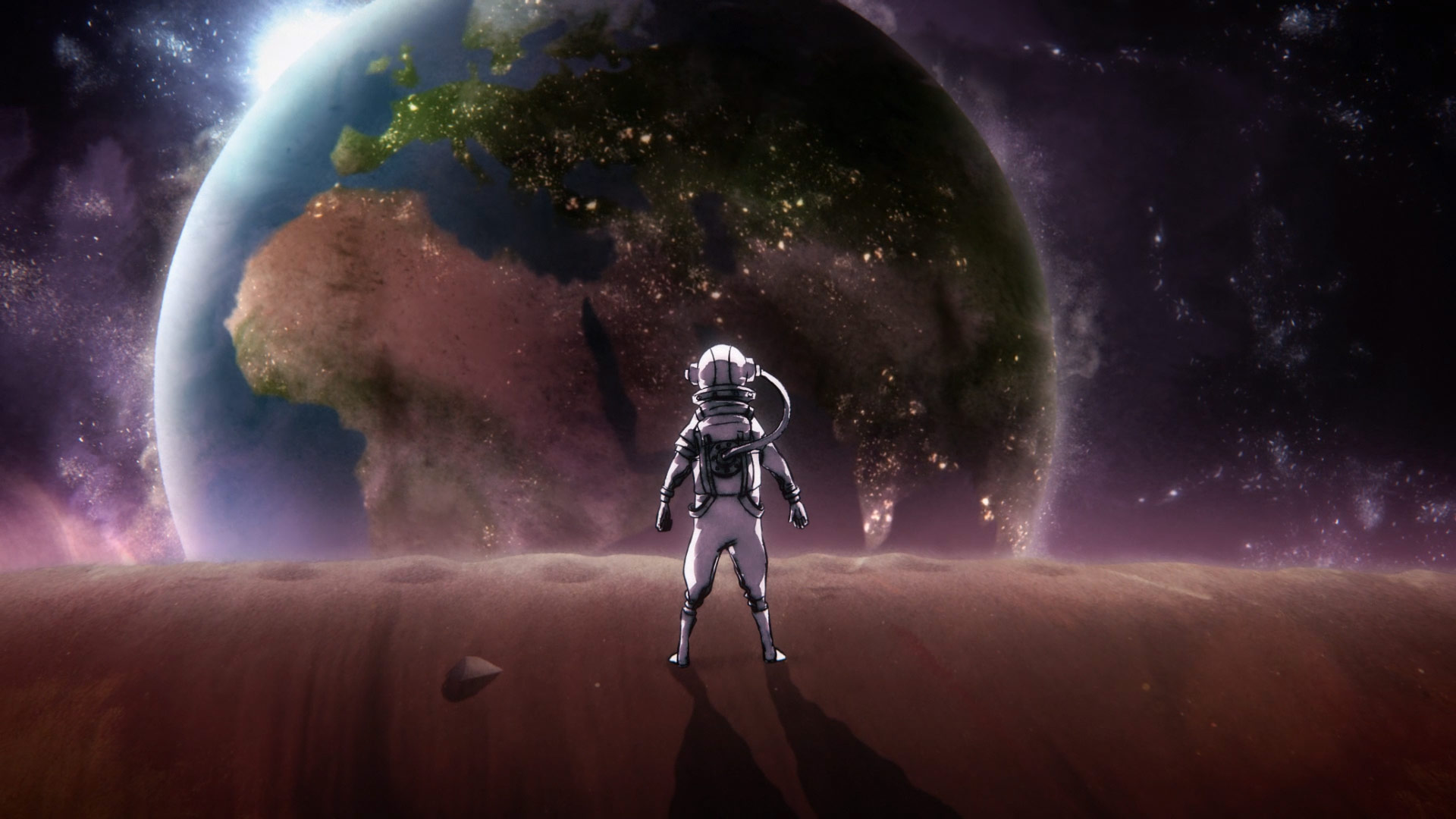

One of three films recently commissioned through YouTube’s global competition The Cut, Iranian filmmaker and refugee Majid Adin imbues Elton John and Bernie Taupin’s classic 1972 hit Rocket Man with the heartfelt emotions of loneliness and hope he experienced as a refugee when fleeing his native Iran for the UK. Following Rocket Man’s Cannes premiere, DN caught up with Majid and Co-Director Stephen McNally, to discover how the pair worked with the Blinkink team for their touching contemporary reimagining of this iconic track.

How did you come to take part in The Cut competition and what went into your winning submission?

Majid Adin: Joe Murphy and Joe Robertson from Good Chance Theatre (who are a charity organisation working with refugees) first alerted me to the competition and encouraged me to apply. I literally had two days to conjure up a treatment which consisted of a very rough storyboard/animatic, some of my personal paintings and some written text which the two Joe’s helped me draft up.

Being selected as one of the winners was absolutely incredible, in fact, I didn’t quite understand what it meant until after the announcement was made and couldn’t believe my luck!

What was your initial approach when translating your personal experiences into Elton John’s well know story of a lone astronaut?

MA: The 1st thing I did was to translate the lyrics of the song into Farsi so as to have a better understanding of the song, and every single lyric immediately struck a chord with me on a very personal level.

The message we wanted to convey in this video is one of compassion, kindness and hope.

Stephen, how did you work with Majid to shepherd the animation through production whilst remaining true to the heartfelt nature of his story? Could you describe the processes and tools used to complete the film?

Stephen McNally: I saw my task as being to help Majid achieve his vision for the film and to amplify Majid’s voice essentially, as well as wrangling the team. We began with extensive rough thumbnail drawings of the scenes. We communicated visually a lot at this point, using drawings to discuss how we would bring the piece to life. Majid and I discussed the story extensively and its non-linear structure.

Majid would make reams and reams of rough scamps of all of the scenes, and any visual ideas he had within them. I edited these into a very rough animatic (just setting the drawings out on a timeline roughly to music) that we could use to discuss how the structure of the film would work. Meanwhile, I was making early tests of compositing techniques we could use to bring the flowing bleeding watercolour paint and rough, textural linework to life, in a way that would capture the aesthetic of Majid’s paintings.

When we had the structure set up, we worked with Storyboard Artist Jay Clarke and Editor Gus Herdman to refine the animatic into the basis for the animation. At the same time, we worked with Character Designer Lauren O’Neill and Backgrounds Design Marion Louw to create assets that our animators and compositors could use straight away. We worked with a team of incredibly skilled character animators, both in studio and remotely, who we would precisely brief on performance for each shot, and we would talk through the roughs as they progressed.

We worked primarily in TV Paint, with a tiny bit of Adobe Animate on the side. Concurrently, our clean-up team of assistant animators took the rough animations as soon as they were done, bringing them together in terms of consistency of model and linework, while maintaining the energy and fluidity that the animators had imbued them with. As soon as an animated shot was cleaned up, we worked up a shadow pass on them and gave the linework and shadow matte to the compositors, where we integrated them into the scenes and gave the characters their unique watercolour-like look. At the same time, our compositing team was setting up the scenes with fluid, flowing backgrounds and elements in After Effects.

We had a makeshift rostrum set up in the studio too, where Majid and I would film elements of ink and watercolour bleeding and flowing into wet paper so that we could capture their natural movements. This way we could immediately create specific elements for the compositing team and have them ready in a few minutes.

How long did you have to complete the film once officially commissioned and in what ways did that timeframe impacted the way the film was produced?

SM: From the week we were putting together the animatic to the final delivery, we had 7 weeks, which may seem like a lot of time, but with this length of a track and with so much full traditional animation involved, time was of the essence. As you can see from the many ways I said ‘meanwhile’, one of the main impacts was that it meant we needed to work on all sorts of different aspects of the film concurrently. Where these processes would often be staggered over the course of a production, here they were all continuously feeding each other at the same time.

There was a constant stream of new things to see and work on and discuss.

While this is slightly like having many plates spinning, it was also exciting, as there was a constant stream of new things to see and work on and discuss. Another impact was that it left us with very little margin for error, very little time for retakes or adjustments. To work with this we would extensively discuss the shots with the animators beforehand, talking through ideas they wanted to bring to the shot until we all had a firm idea of where shots were going. The animators would block out key positions really roughly, so we could adjust or affirm before going too far down the line.

That said, what really helped was working with such an amazing team of consummate professionals who consistently hit the mark first time. It’s a joy to work with a team you know you can count on. Everyone really connected with the story and the subject, and were determined to give it their all.

In a time when countries are tightening their borders against ‘outsiders’, what do you hope audiences take away from this story?

MA: The message we wanted to convey in this video is one of compassion, kindness and hope.

What projects do you have coming up?

MA: My aim for the future is to continue working with Blinkink to create a new short film by the end of 2017 and dream of one day scooping an animation Oscar.