God I miss dancing! While cranking my headphones to full and busting some Risky Business moves at home has its place, it doesn’t hold a candle to heading onto packed dancefloor blaring out your favourite tunes. Channelling this yearning for the time before enforced stillness and separation into a transfixing fusion of rotoscoped dance and heavily stylised design, Serafima Serafimova’s Still Life artfully celebrates the beauty of movement and human contact across 90 transfixing seconds. Making its premiere here on DN today, Serafimova returns to our pages to reveal how analogue drawing techniques shaped Still Life’s animation style and why embarking on a personal project was a much better alternative to the other lockdown distractions she could have taken up.

As a fan of your portrait work, I’m curious about the link in techniques and styles between that and your animation. How does one inform and build on the other?

With my portraits, I am always searching for a likeness in its simplest form, without overworking the drawing. It’s basically an exercise in translating a person’s face onto the page by using as little information as possible and allowing the audience to fill in the blanks. Finding the right animation style, on the other hand, is a little bit more complex than that. As each animation has its own theme and voice, the design, style and colour palette need to reflect that, so it involves a fair amount of research, trial and error. Even when I think I’ve found it, my style naturally evolves throughout the process, so usually by the time I finish each piece I end up hating the first few scenes in it.

I decided to explore the things I missed the most – the ability to move freely and to be close to the people I love.

Several filmmakers have told us that they feel a pressure to be ‘extra’ creative in lockdown. Is that something you experienced during this mandated period at home?

It didn’t really feel like pressure to be honest. It felt like an opportunity. For the first time since I graduated, I had enough time to work on a personal project, without having to do so around my full time job or getting distracted by playing sports, going out with friends and basically having a life. Like so many others, I too felt compelled to create something inspired by COVID-19, so I decided to explore the things I missed the most – the ability to move freely and to be close to the people I love. Ironically, I now realise that Still Life was, in fact, a distraction in itself – keeping my mind and my hands busy, shifting my focus onto the animation and away from the craziness that was going on around me. It was either that or drinking myself to sleep every day…

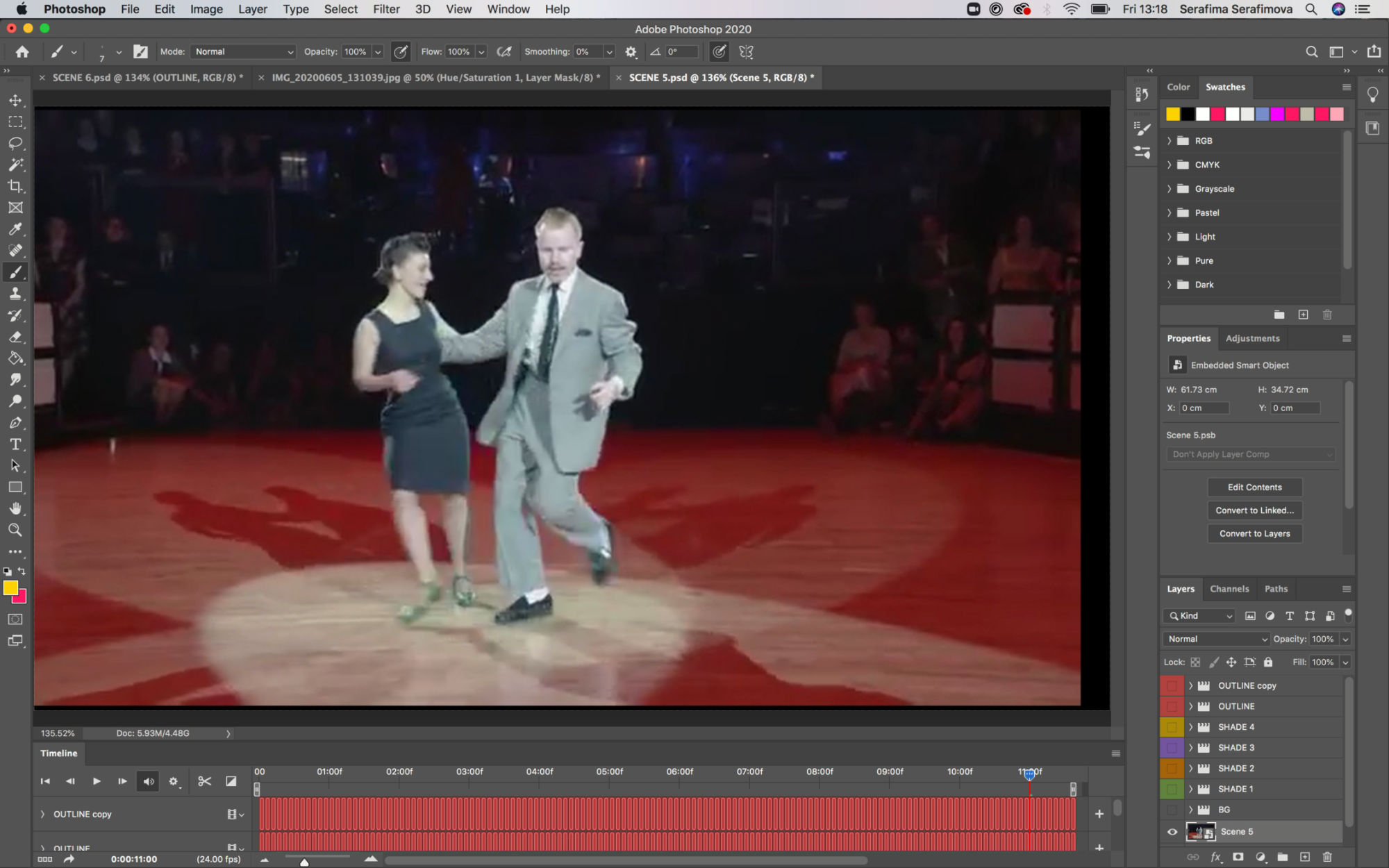

What were your parameters when selecting the source dance footage to rotoscope?

Initially I had three criteria – the pairs had to be distinctly different from one another, they had to dance in time with the beat, and they had to look cool as f*ck doing it. Then came the painstaking job of finding clips which looked the part, worked with the music track AND had similar choreography which could potentially be matched in the edit for a seamless transition between the dancers. Finding these involved ploughing through hundreds of YouTube videos and testing if the cuts worked – by far the most important and frustrating part of the process. Thankfully, as a video editor, I’m pretty used to it. 🙂

Could you tell us how your choice of digital tools were informed by their physical counterparts?

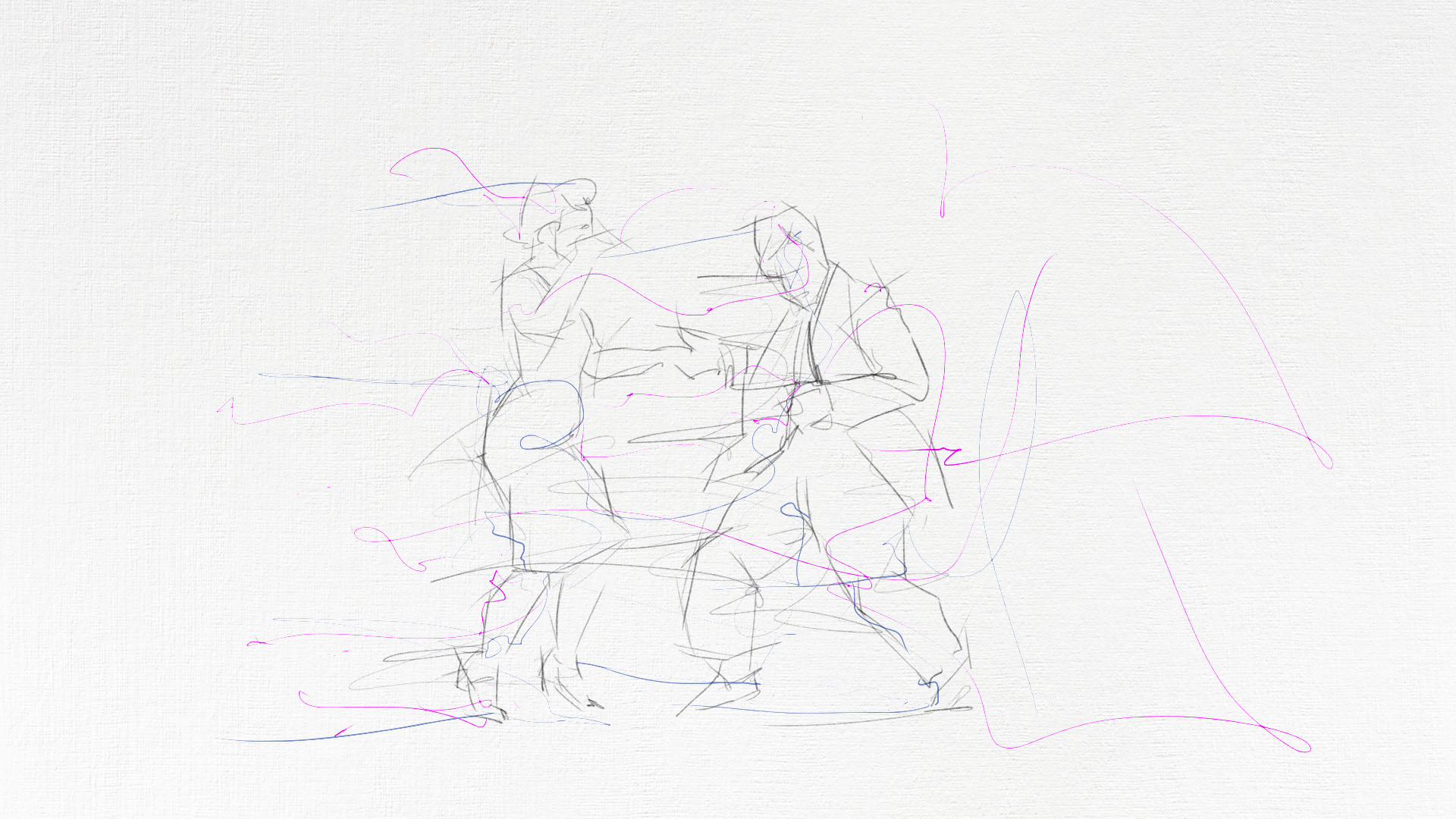

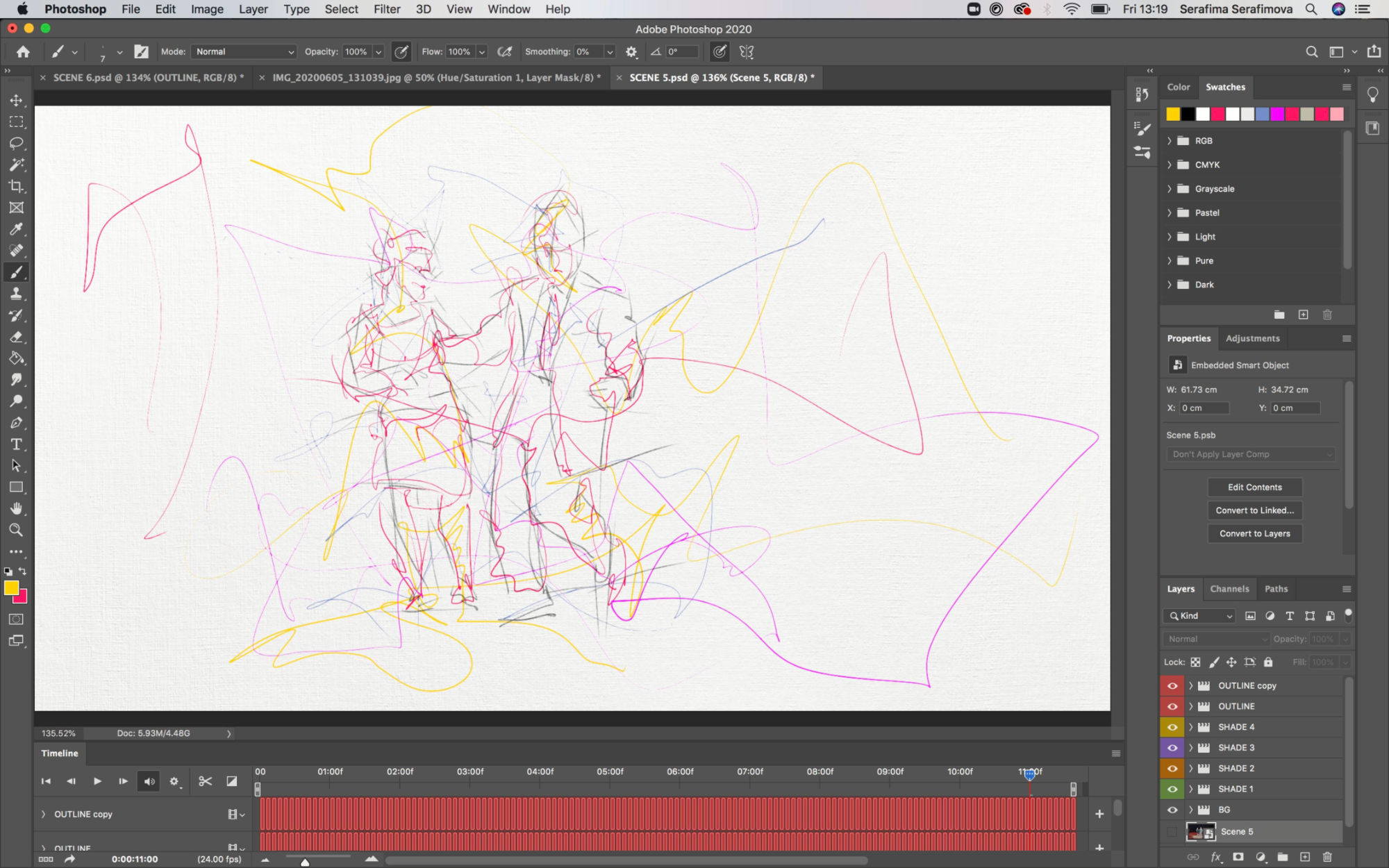

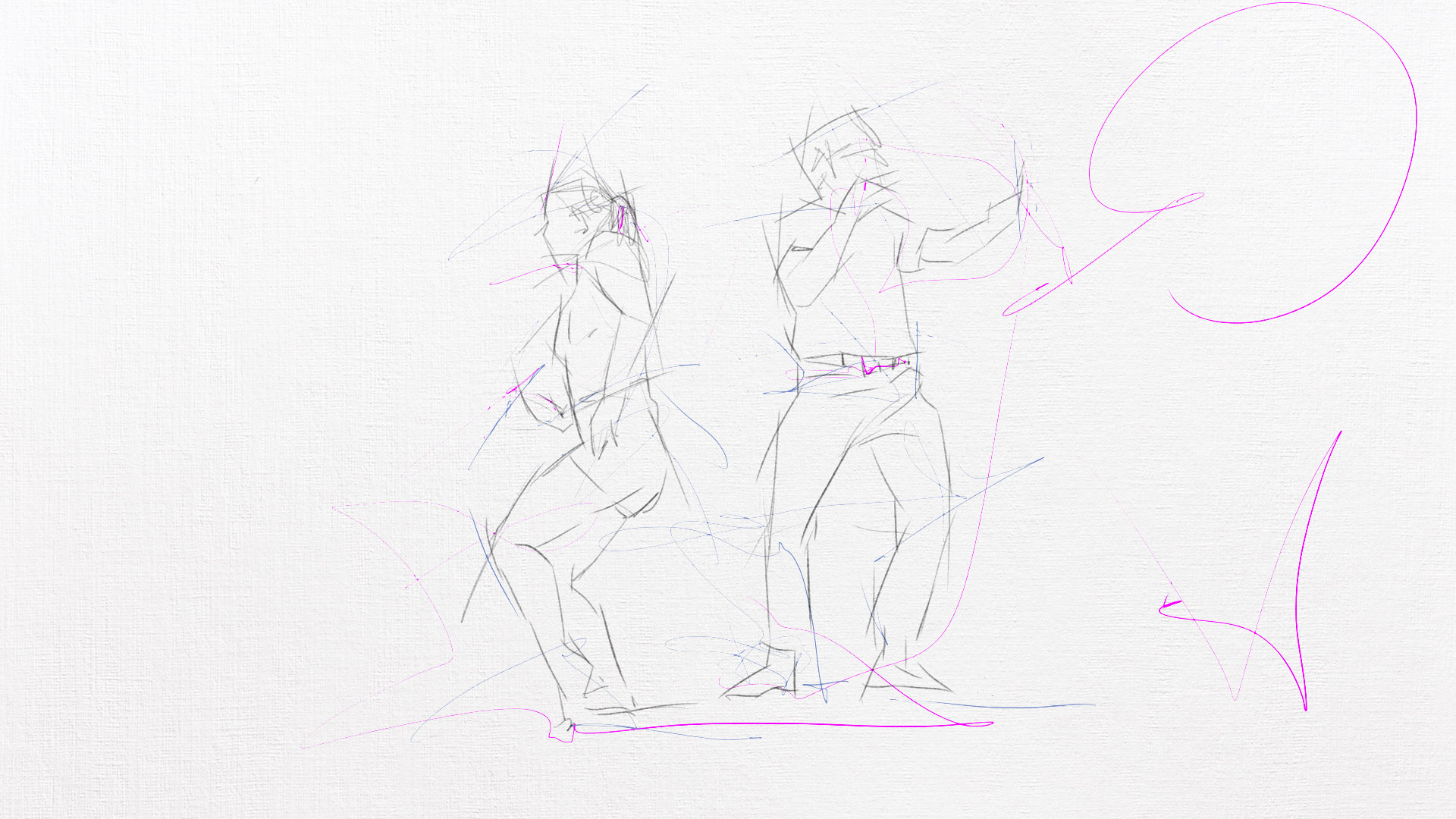

I’ve been going to life drawing classes for years. It’s an incredible experience where, for just a couple of hours at a time, I can both feed my fascination with the human body, and enjoy the company of a different penis to the one I’ve lived with for 15 years. It’s another thing I have missed terribly since the lockdown, so the idea to create an animation which looked and felt as though it was a physical work of art that’s come to life, came pretty naturally. To get the full effect, I decided to stick to the digital brushes and textures that were the closest to the media I usually use in my art – pencil, biro and charcoal, and I used those pretty much exactly the way I would if I was drawing a quick, 2min pose – with big, bold strokes to quickly capture the shape and movement without worrying too much about the small details.

The idea to create an animation which looked and felt as though it was a physical work of art that’s come to life, came pretty naturally.

As with Flawed before it, you again use morphing transitions, this time employing bursts of colour. How does their function differ from that previous project?

The transitions in Flawed represented the notion that women of all backgrounds share the same body-related hang-ups. With Still Life, it was all about building momentum in the animation in order to keep the audience engaged throughout since there wasn’t a clear narrative. Adding colour was a great way to do that, but I also discovered that working on the colourful, chaotic scenes did wonders for getting my frustrations out, so I usually saved them for those extra miserable days when I felt like stabbing things.

Still Life’s minimalist images beautifully teeter on the edge of visual comprehension yet never fall over into confusion. What’s your process for finding the level of near abstraction which would still be intelligible to audiences?

When I animate I often have to fight with myself. The portrait artist in me always strives for perfection, and it’s very tempting to get hung up on every frame, trying to make it look good as a standalone drawing. Then I remind myself that no one will judge that single frame on its own, that it only serves as a tiny fragment which together with 11 others make up just one second of animation, that you can miss altogether if you even blinked.

Since Still Life was all about celebrating the beauty of movement, I wanted to keep the style quite sketchy and elusive, so that it captured the energy of the dancers but avoided details like facial features and skin tones. I was hoping to achieve a sort of fluid, mesmerising effect which just felt good watching it – a tiny pleasure during a time when we’ve been bombarded with negative imagery and frightening news.

It was important that the dances didn’t fit the track at all, yet at the same time they fit so perfectly well.

The disparity between Ofrin’s track Mythologica and the formality of the dances bonds the film together in a way that’s difficult to articulate. Did you have to try on a lot of music before finding this match?

I actually found the track first! I stumbled across it whilst browsing through Artlist, trying to find a music track for a different project I was working on. It immediately got stuck in my head and that, combined with the fact that the lyrics contained the word ‘couscous’, sealed the deal for me. And yes, it was important that the dances didn’t fit the track at all, yet at the same time, they fit so perfectly well. Hopefully, that disparity brings a bit of playfulness and a sense of surprise which keeps you guessing.

Obviously I have to ask when we’re allowed to hit the dance floors once again what’s the track that’s going to get you up on your feet?

Anything by The Strokes!!! Their music just fills me with joy! It’s also one of the few bands I haven’t managed to see live yet, so I’m dying to do so when normality resumes.

How’s the childbirth project coming along? Is that what we’ll see from you next or do you have something else currently in the works?

HA! I did actually ask a friend if I could film his wife when she was about to give birth, but he wasn’t that keen on the idea for some reason, so I’ve shelved that for the time being. However, my new project also happens to be about motherhood. Together with three incredibly talented friends of mine, we are in the early stages of developing a live-action short about a young family, and it will be filmed entirely from inside the oven. I promise to keep you posted 🙂