Sam Stillman hits the kinetic streets of New York for his latest short film Let’s Get Lost. Set in a bustling jazz bar, Stillman follows Ozzy, the owner, as she comes in contact with a raft of eccentric characters whilst navigating a night of turmoil and surprise. It’s a brilliantly visceral experience and one that will whet the appetite of John Cassavetes and Safdie Brothers’ fans. DN caught up with Stillman to talk photography, powerful performances, and the unpredictability of a brilliant film crew.

Where does a film like Let’s Get Lost begin?

I mean, it started with talent, our lead actor Stella had mentioned to our producer Eléonore she was looking for something to do, and Eléonore knew Stella was an important actor and told me and that’s all I needed to hear. As an actor Stella is such a powerhouse, such a mixture of force and vulnerability, has such capacity, is capable of anything, it’s very hard to find something to challenge her, so the idea came that she should play someone dealing with others, forced into reaction, whose innate human glory needs an avenue, an action, and to find that avenue in getting out of the way. I mean, it’s a movie about making movies, finding incredible talented people and getting out of the way.

It feels like a film embedded in classic filmic language, what kind of discussions did you have with your collaborators when initially developing the idea?

Our images were made by two cinematographers, Hunter Zimny and Sean Price Williams, both of whom I would say, from my limited perspective, come from an incredibly strong ‘people-first’ ethic. We filmed on an Arri Alexa, with Zeiss super speed lenses. There was very little interest on anyone’s part for any fancy camera tricks or distracting technique, but just making sure we were rolling on these incredible performances, hopefully accentuated by little touches of classic filmic language.

Photography is always sort of like a gravestone of intense transience and fragility made immortal stone by a camera.

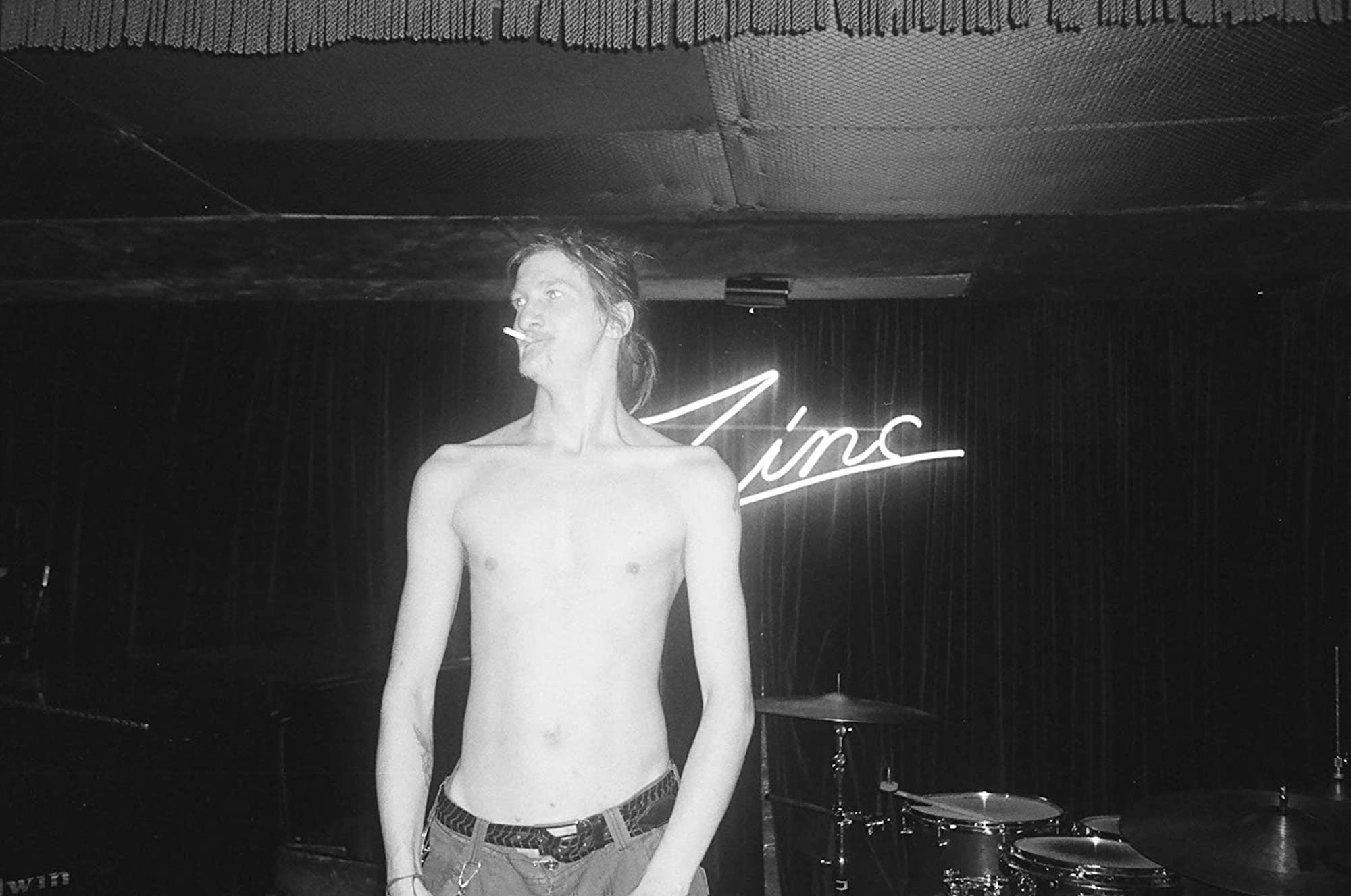

With Sean, we looked at some photos by Ed van der Elsken, Love on the Left Bank and his book Jazz, both of which are just transcendent. The composition only serves in a devotional aspect to its subject, the beauty, glory and humanity of its subjects, and to cut off a revelatory moment of their lives into this glorious, tragic, vulnerable and powerful captured image. Sean was already a huge fan of his and showed me some videos I hadn’t seen, and just the fluidity of the images, how in one frame you can feel an entire life. Photography is always sort of like a gravestone of intense transience and fragility made immortal stone by a camera.

Was there anything specifically that aided the kinetic nature of Sean’s cinematography?

Sean loved the contrast of the images, which he said you only really get in black and white, which we didn’t do. Sean also sent me this beautiful little movie, I think the only motion picture film taken by Weegee, called Weegee’s New York, which has a sort of kineticism and sense of fun that we hoped would be important to filming.

How did having two cinematographers affect filming, did Hunter bring anything different to Sam?

Hunter of course comes from the same ethic, and though Sean was interested in the cast, Hunter was only interested in the cast. He read the script, so he could anticipate certain moments, but he was drawn to these faces like a moth to light. Hunter is aware on a cellular level the work of Ed van der Elsken, Weegee, the cinematography of Sam Shaw and the Maysles, etc. That really comes from the almost documentary approach of subject-first filming. Through long shoots the only thing that kept him going was these faces he has to, on a cellular level, record.

Editing Sean and Hunter’s footage was like cutting florentine silk, the pleasure of a lifetime. Because of that, their skill, editing this movie took about five days, with another two to polish with Stephen Gurewitz, who made, small, deft changes that decimatingly accentuated the scenes.

It’s beautifully lit. Is that New York’s natural hue or did you create that?

Arseniy Grobovnikov, our gaffer, worked closely with Sean and Hunter, and really tried to light the environment in a dynamic way rather than light the shot, so the production could really be centred around the actors rather than around lightbulbs and lenses. We showed up one place, I asked “What lights do you want?” and he said “None”. An artist.

It’s a movie about making movies, finding incredible talented people and getting out of the way.

Your characters are so striking too, each of them feel so individual, how did you conceive that?

Bruno Dicorcia, who did the clothes, had just such an instinct of beauty and grace. He, Eléonore and I spent a week in preproduction getting all these clothes together, and every bad idea I had; leather hats and big rings for Ray, sequins for Maxine, and a zoot suit for Jack. He was able to take the spirit of it and make it much more beautiful, and dignified for both the cast and characters. When Stella showed up in her own wardrobe, and Leaphy Wyndragon in his, Bruno, like Arseniy, just said “perfect” and left.

It sounds like you really established a great group of characters. Did shooting so viscerally in New York inherently create any fun stories?

There’a great story with our Production Designer Audrey Turner. There was this little purple snakeskin purse, this purse, it never got anywhere near being in frame, I didn’t know about it, I don’t even think Stella knew about it. Anyway, I open it, and there’s all these little things, little candy, change purse, little religious icons, keys… and this little slip of paper. I opened it, and it’s a to-do list. It’s a to-do list, for Ozzy. Audrey had made Ozzy a to-do list, in it was personal, private, beautiful errands and questions, it could have been its own movie.

Audrey was never on set, she worked for four days in preproduction and we would just receive these packages from her, Ray’s engraved trumpet from a collector in Bayside Queens, plaster cast Cherubin for the piano, green lampshades, the neon sign, a tiny stone pieta for Ozzy’s desk. Everything was perfect, exactly what the movie needed and then better than that, her to-do list for Ozzy was perfect. Charlie Robinson used these to dress the set beautifully. I called Audrey some time later and she denied all knowledge of the list.