In making Museum of Fleeting Wonders, Tomas Gomez Bustillo has crafted a beautiful collection of quotidian vignettes. Each of these short stories, which were submitted to Bustillo by friends, family and even a few strangers, capture a moment of everyday life in all its magical glory. This sense of powerful simplicity is reflected in the cinematography too with minimalistic static imagery being encased in a 1:1 aspect ratio, drawing the eye into focus and reflecting on each of these small yet compelling moments. DN is delighted to premiere Museum of Fleeting Wonders on our pages today and invited Bustillo for an in-depth chat about his chronicle of everyday majesty, discussing everything from the initial impetus to the heavy preparation he did to not over-complicate his shots, and the challenge of maintaining his driving creative mantra: less is more.

What’s the starting point for a film like this? It feels quite singular in its vision.

The project started out of the simple wish to shoot something. It was 2019, it had been two years since my last short and I wanted to practice working with non-actors, as well as try my hand at the kind of magical realism I had envisioned for a feature screenplay that I was developing at the time Chronicles of a Wandering Saint, which is currently in post production. At the same time, I wanted to try doing something with a minimal narrative, something that worked purely with sounds and images, and that could also lend itself to being watched on social media, not just in film festivals.

One of the ideas that kept giving me direction during this whole process was the idea that for this project, less is more.

I started developing these ideas with my producer and eventually I landed at the idea of a sort of visual gallery, a collection of short stories, grouped around an experience of something uncanny, otherworldly, within the ordinary. It would be a museum of tiny moments, almost insignificant except for a single, fleeting moment of doubt. I wrote a kind of statement of intention, trying to act as a sort of ‘curator’ of this weird gallery of stories, trying to define what fits and what doesn’t, and why. From there, we asked friends, family and strangers for stories, and used them to write this collection of shorts, making sure that they presented variety within the same theme: some were more mysterious, some more comical, some dark and some uplifting, but always strange, minimal and wondrous.

I imagine it’s the kind of project where you have to resist over-complicating these ideas too. How did you approach each story when it came to capturing its essence?

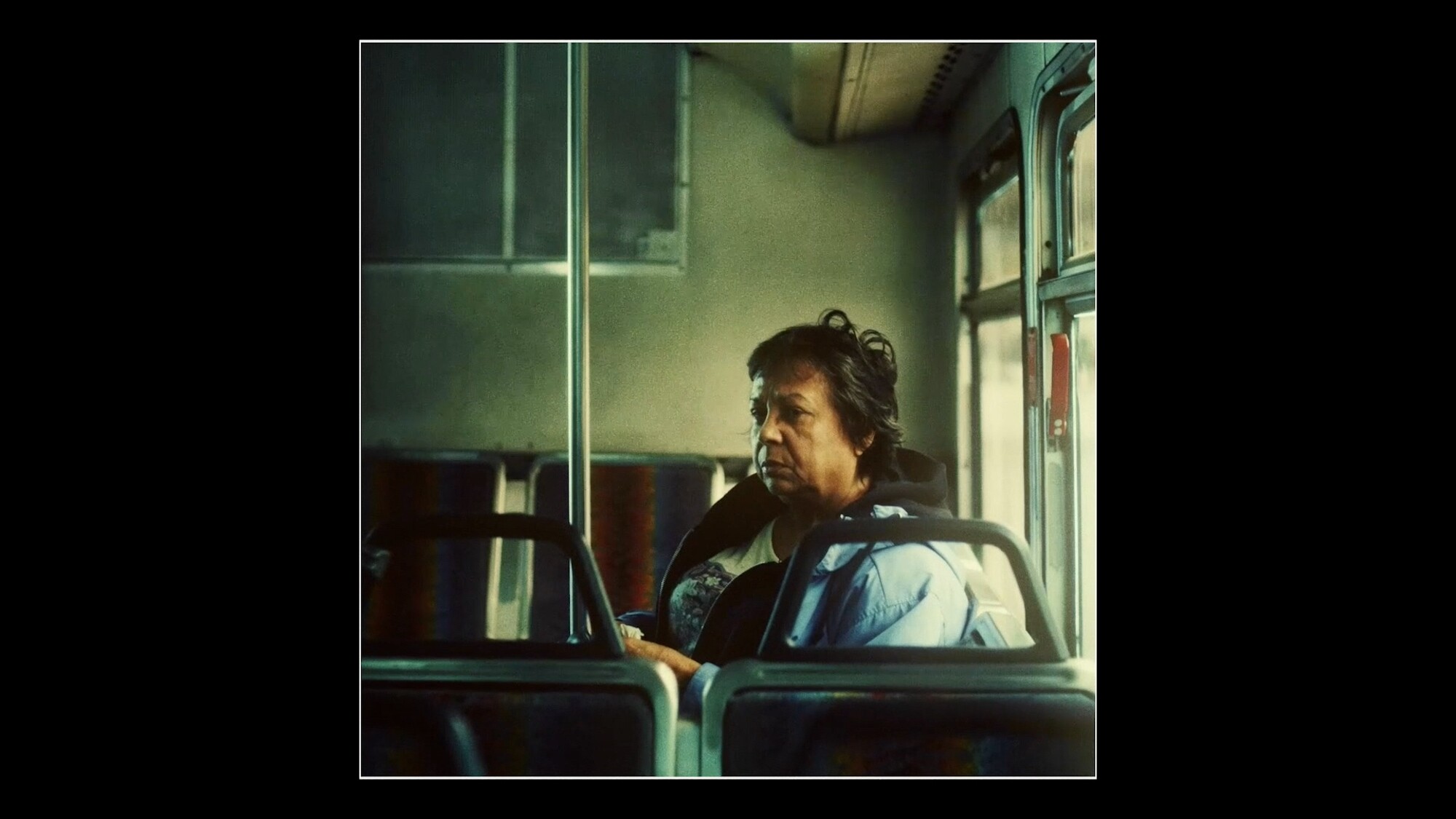

One of the ideas that kept giving me direction during this whole process was the idea that for this project, less is more. During pre-production, we focused on two key elements: locations and storyboarding. We wanted locations that were very simple, to the point of feeling almost abstract. A vacant parking lot, the back of a liquor store, a bus, a house, or a rooftop. We wanted these to feel like they don’t belong to one particular city, but instead could belong to almost any urban setting around the world. That meant the most minimal, bare-bones version we could find of these kinds of places. The end result was shooting in different locations across Los Angeles and Lancaster.

As for storyboarding, the less is more motto translated into an observational style that was extremely utilitarian and restrained. That meant that our main concern was camera placement and composition. The less we interfered with the flow of the scene, the more the tiny magical moments could shine. We spent many days storyboarding with our DP, PD, and producer. It was during this time that the 1:1 aspect ratio was consolidated as one of the main ways the whole film would feel like being at a museum, hopefully reframing the viewer’s interaction with the piece: less like watching a movie, more like moving through a gallery.

How long were you shooting in LA and Lancaster for in total? And how did you approach casting, did you use actors?

Production took about five days, scattered throughout LA and Lancaster. We had a small team of about 10-15 people, depending on the day. About half of the cast are non-actors: people we had encountered on the street, in restaurants or life in general. The idea behind this kind of casting was to bring people into this film that felt like they could be your friends, family, neighbors or co-workers. Since we had heavily storyboarded, the production itself was relatively smooth, except of course your standard indie production mishaps like being kicked out of one of the locations and getting trucks stuck in the middle of the desert. It was shot on an Alexa Mini with Super Speeds.

Did thoroughly preparing for the shoot aid you in post-production? And did you approach music in a similar, less is more, way?

We started editing very soon after production, and after a couple of weeks, had a cut we felt very strongly about. One of the biggest challenges was the music: our first passes with the film composers were heavily musicalized. We soon realized that of course, less is more, and started to use music only in the transition spaces in between stories. The instrumentation also became quite minimal, going from strings and percussion to a single percussive element, a little wooden musical box. Echoing the square aspect ratio, we explored all the ways it could be made to sound. It was a very enjoyable discovery process. Similarly, in color, we gave the film a more nostalgic look, like something found in a gritty 16mm archive, so that it made these pieces feel like something that was long lost, only recently uncovered, hopefully enhancing its secretive, magical qualities.

I landed at the idea of a sort of visual gallery, a collection of short stories, grouped around an experience of something uncanny, otherworldly, within the ordinary.

My favourite story is the hysterical nun. There’s something so wonderfully strange about that scene. What drew you to opt for it as one of the stories in Museum of Fleeting Wonders?

My biggest concern with the nun story as soon as we sourced it was that it would play as too overtly comical and would not feel otherworldly enough. But like you said, something about it just kept me going back, feeling like it was a necessary part of the series. It was the absurd combination of otherwise mundane elements that intrigued me. The nun, the plastic bag, the laughing. And what we found in crafting the final version that you see in the film was that it was essential that both the protagonist and the viewer never found out what was actually inside the plastic bag. The unanswered question was the key to making this story fit into the series. That’s where the otherworldly, mysterious element fit in. What could possibly be in a plastic bag that would make someone laugh this much? It’s so unlikely it’s almost paradoxical, and that’s where it starts to feel unreal, uncanny.

Why did you ultimately select the stories that made it into the film over the other submissions?

After asking friends, family and even strangers to tell us their stories of lonely, strange encounters with something otherworldly, we used them as inspiration to write the ones that you see on the film today. They represented a group of stories that would help convey a larger arc, something of a narrative experience for the viewer. We would start with something that could hopefully ignite the audience’s curiosity with the lightbulb story, then draw them in even further with the absurdity of the nun story, both unsettling and comical. Then we would transition into the darker set of stories: the more otherworldly tone with the woman on the bus and the subtle violent undertones in the bird story. Finally, we took a long time to source and tweak the final story, that would wrap things up on a thematic level and give the viewer both a sense of openness and mystery. So in short, choosing the stories was all about creating a narrative arc as you experience the Museum.

What will you be working on next?

Right now I’m in the post production process for my debut feature Chronicles of a Wandering Saint for the next few months. This film has many, many similarities with Museum, both aesthetically and tonally. Hopefully, over the summer, as we start to send that film out into the world, I’ll be developing and writing another screenplay, which I intend to be my first English speaking feature. I have a few treatments that I’ve been working on in the past year, and unfortunately, can’t seem to do anything other than pursue the kind of magical, slightly comical, slightly strange types of stories that I am drawn to.