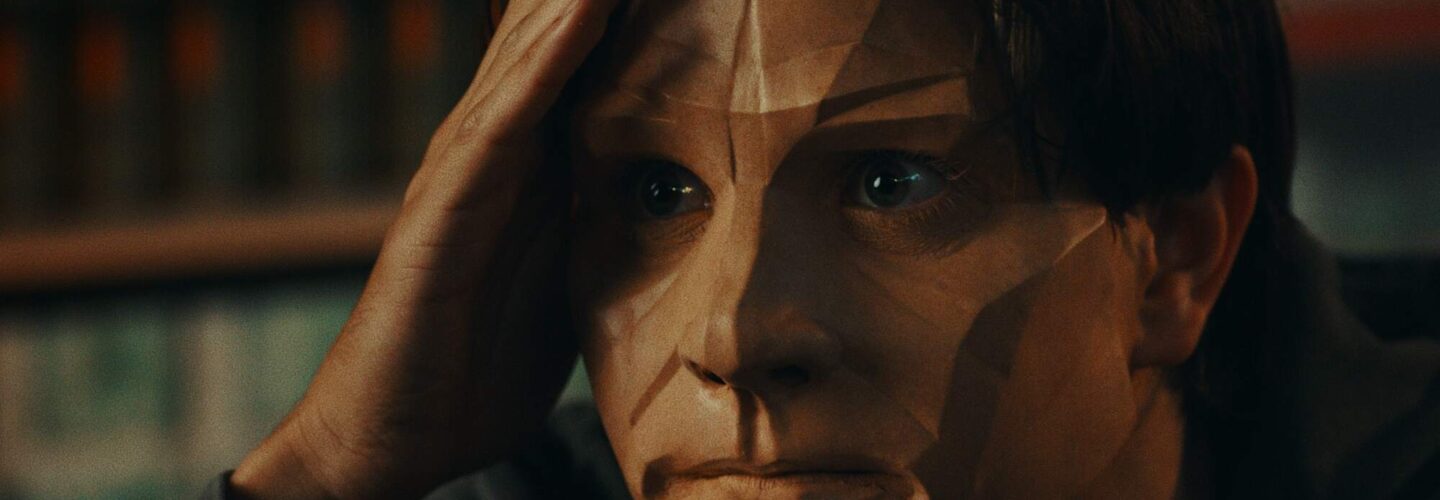

Director Omer Ben-Shachar’s short film/music video hybrid for Claudio Olachea’s Down Here sees a strange dystopian world where people wonder the streets donning identical masks that allow them to blend in amongst one another. The short focuses on one individual in this society, Elijah, who finds himself desperately trying to comply with these rules until an ounce of doubt begins to creep in. Ben-Shachar’s story is one of identity and performance, questioning the role metaphorical masks play in our real world. The masks in Ben-Shachar’s world have disconcerting look to them with an uncomfortable angular smoothness to their design, this characteristic is carried into the overall look and feel of the short too which proves a compelling companion to Olachea’s track. DN spoke with Ben-Shachar about his ongoing collaboration with Olachea, the natural evolution from sci-fi to horror that Down Here took, and the creative choices that manifested its ominous disposition.

What was the beginning of this short and your collaborative relationship with Claudio Olachea?

The film was born out of Claudio Olachea’s gorgeous Down Here track, which he composed along with five other songs he’ll be releasing soon as part of his debut EP. I’ve known Claudio since 2018, when he composed music for a short I directed and co-wrote, Tree #3 (2019 Student Academy Award winner). At the time, we both had such a similar work ethic that it became almost scary at times. We could obsess over five seconds of score for days. Two perfectionists who question everything and shift things around constantly is not recommended. There was always room to make things better. Luckily, we had a deadline. Thank god for the deadlines. However, for Down Here, we didn’t have a deadline which meant we had too many opportunities to switch stories, and of course, we did. We actually started off with a very different story, focusing on a romance between two suitcases. As the story kept evolving, we somehow magically arrived at our current story, which couldn’t be any more different than a love story about two suitcases.

For sure. It’s a short that seems to question the performative nature of identity, at least that’s how I read it.

The current story of Down Here definitely came from a personal place. Growing up between Tel Aviv and Texas, I always felt as if I had to put on a different identity depending on where I was trying to fit in. Not only did I feel like I had to be another version of myself with different people and cultures, but after a few years, I started to get confused about who my real self was. Of all the different identities, which one was the ‘real me’? This is something that I still question. When someone says “just be yourself”, I always want to ask them, “which one?”.

We all put on different masks when we leave home, hoping that by eliminating some parts of ourselves and showcasing others, it will help us connect with others.

This is a synergy between Claudio and I. Claudio is the son of a Mexican immigrant whose childhood was marked by frequent moves and nearly a dozen schools in five different states, leading to a lifetime of questions rooted in identity and self-image. These shared experiences made the journey of Down Here a truly personal one for us both.

In regards to your creative identity, do you see any relation between Down Here and you other shorts?

A few weeks ago, when I sent a rough cut of Down Here to my friend, her first response was “you did this?” I immediately said “thank you”, thinking it was a compliment but then I realized she was literally asking me if I did this. She couldn’t recognize me in it. My past work has never been this dark, and it felt to her like someone else made it. That was so interesting to me because that’s exactly what the film was asking, too, who is the real you? Do people recognize when it’s really you, and most importantly, can you recognize when it’s really you?

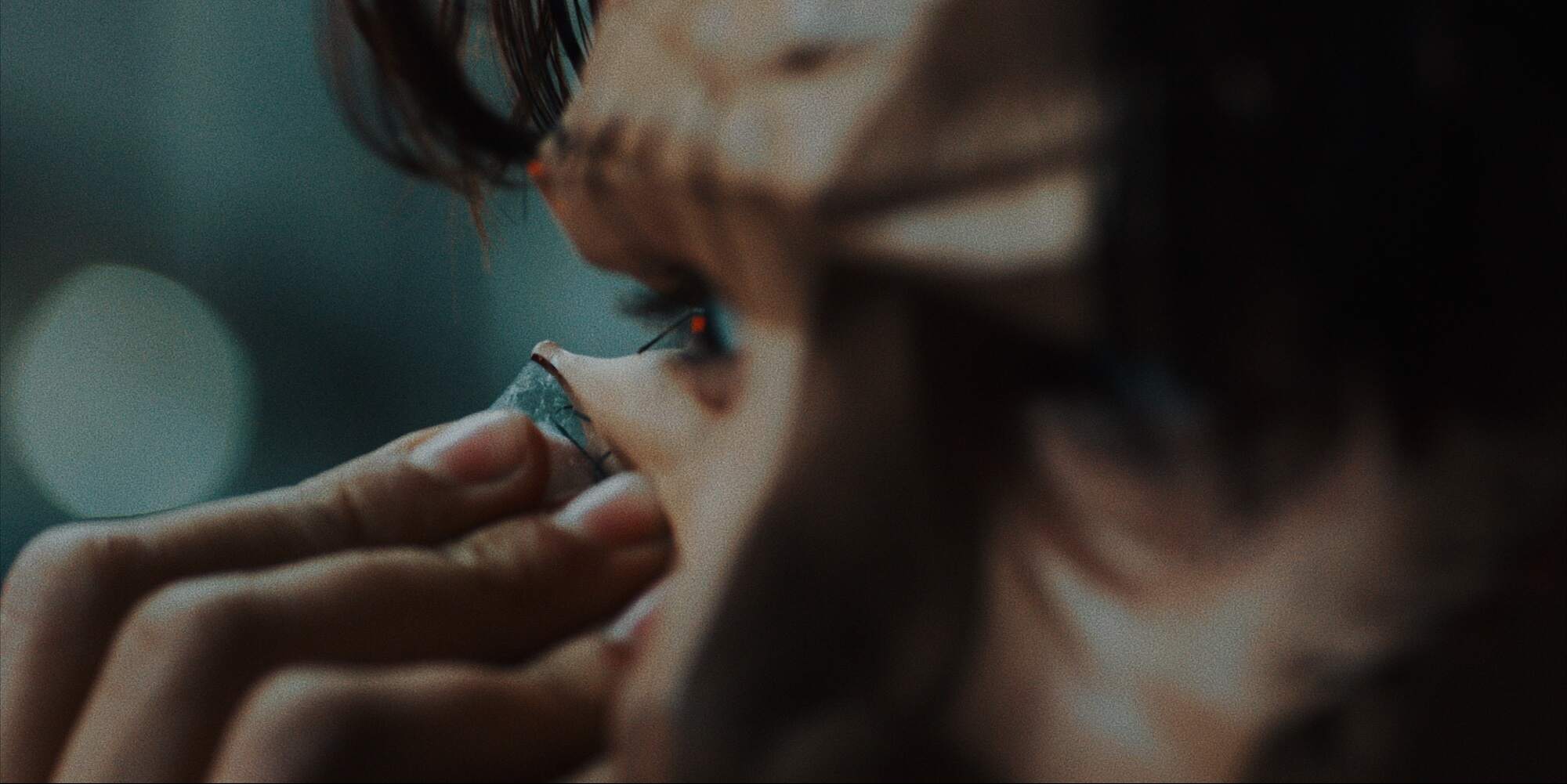

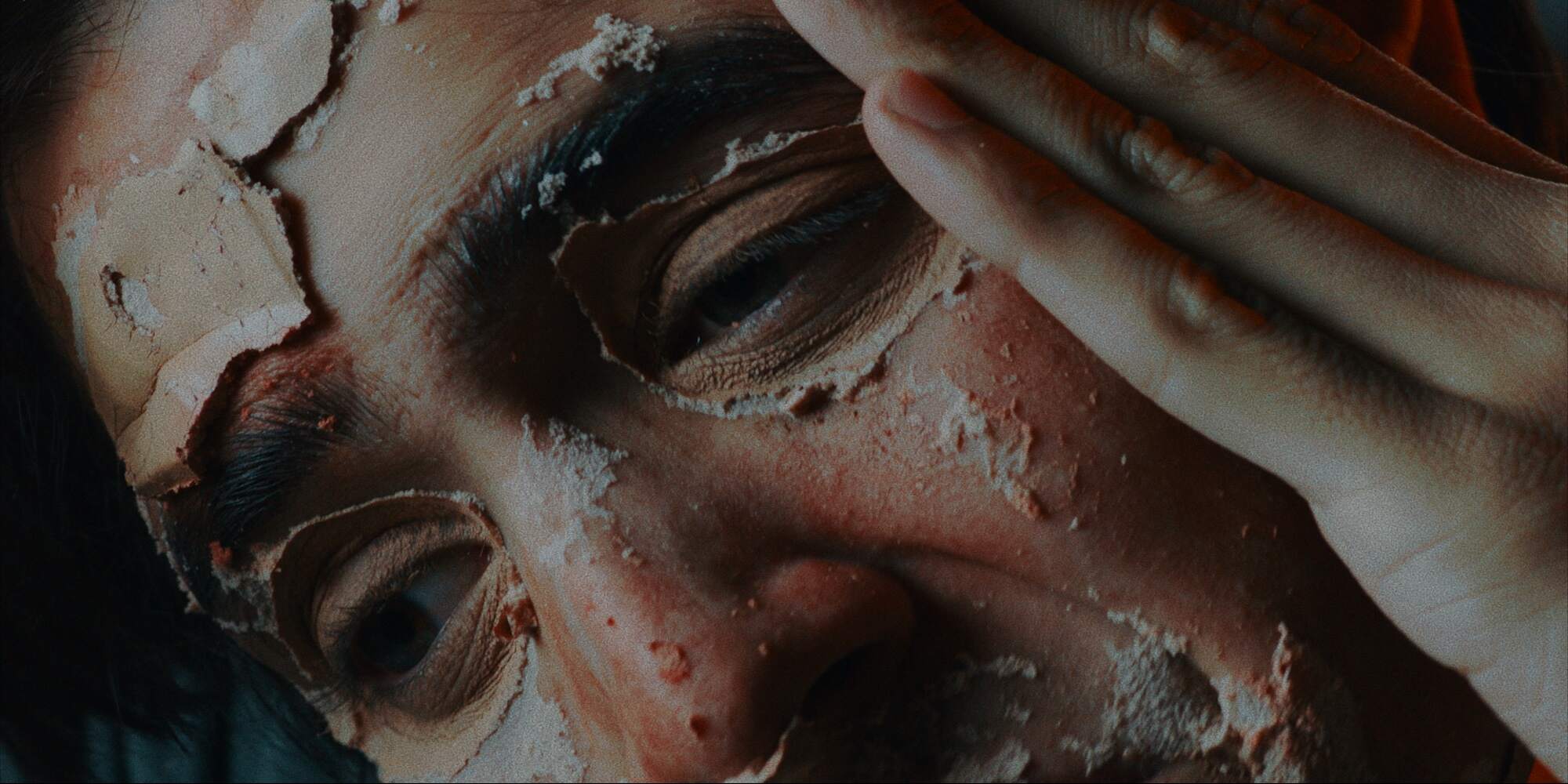

We all put on different masks when we leave home, hoping that by eliminating some parts of ourselves and showcasing others, it will help us connect with others. But so often, it does the complete opposite. That’s where the idea for the story came from. What if everyone had to wear an identical mask when they left their homes? And what if one person was so scared of accidentally revealing his real face that he went to extremes and super-glued the mask to his face? To make things worse, what if everyone else started revealing their real faces as trends changed, but our hero had gone too far and couldn’t change back?

When did you first hear the song and what were your initial thoughts of the track?

I first heard a draft of Down Here in August of 2021. I knew I would like it before Claudio even pressed play, just because of how nervous he was. He really didn’t want to play it for me. I had to beg to come into the studio to listen to it. But I knew his nerves meant he had done something that was so connected to him, something he really, deeply cared about and wanted to protect, and that almost always means it will be good. Especially if it’s coming from Claudio.

How is your relationship with Claudio as an artist? Did he have any input on the vision for the film?

Claudio is a true artist and a dream collaborator, he always encourages me to take the biggest risk I can take, to go darker and creepier and messier. I know he does the same with his music, too. Listening to it, I know that every string or drum beat has been carefully considered, tossed out, put back in, re-recorded, put back in, tossed out again, re-recorded, you get the idea. And when you listen to his stuff you can just feel all those layers underneath. Maybe that’s a big part of what experiencing art is, getting insight into the trial and error, seeing all the faded pencil strokes, all the things that were erased.

The thing I’m most fascinated about with filmmaking is the moment when a film gets a life of its own, and starts telling its creators how to make it. You’re not in control anymore, and you’re left with two choices: you can either listen to what the film is telling you or try to go against it, which usually isn’t a good idea. In our case, we let the film take us toward a much darker tone than both Claudio and I originally anticipated.

All of our creative choices revolved around making the film feel like being stuck in your worst nightmare.

What was that moment on this short?

I think the first moment we realized just how creepy the idea was was during a makeup test a month before the shoot. It was important for us to see the prosthetic on the actor beforehand since the whole film was built around the concept of the mask. Seeing Fernando Siqueira, our lead, in the prosthetic mask, which was done by the brilliant Marina Stearns, was truly terrifying. He was unrecognizable, even to himself.

From there, the tone of our film started to form, with the help of our brilliant DP Kai Krause. We replaced our sci-fi references with horror ones. All of our creative choices revolved around making the film feel like being stuck in your worst nightmare. Kai was there with us throughout the whole process, involved in the story, the budget, and the post. His cinematic point of view appears in everything he does. The first time he saw the location, Kai took some photos, you know, like a typical scout. But he would place the camera in places I’d never thought of. Instead of taking a standard wide shot, he went to the corner of the room, got onto his knees, and took the wide from an extremely low angle, highlighting the crazy ceiling lights the location had. Kai also had the idea of using a Snorricam, inspired by a Requiem for a Dream Snorricam sequence, with an extremely wide lens (18 mm R) for one of the scenes.

Was a lot of Down Here created with that kind of spontaneity or was there a degree of planning in place too?

We video storyboarded every shot with our iPhone, on location, something I was taught to do back at AFI, and have done so ever since. Then, we edited it to the music to make sure we were accurate about the lengths of each shot. We actually went back to the location and re-did the storyboard. Telling a narrative story to an existing musical track, without having any cutaways or ability to change the length of the song, is a challenge. If a shot isn’t long enough, you can’t fill that gap without moving everything else out of sync. And if a shot is too long, you have the opposite problem. On top of that, the number of shots we had to get was close to impossible, 40 in one day. So the storyboards really helped us be concise and precise on the day.

Who else did you work with to bring together the film in post? And how are you reflecting on the input of the entire crew in general?

I edited the project and got the help of my dear friends Shahar Beeri and Shay Asheri to add the final touches. The entire team was incredible, from our producer Thomas Hartmann, who’s the calmest, coolest person you’ll ever see on set, to the lead, Fernando Siqueira, who brought so much of himself to the role. The phenomenal makeup team led by Marina Stearn, who made me want to add prosthetics to every project I’ve done since. The production design team led by Al-E Mcworther, who made the impossible happen by transforming an entire grocery store in three hours. Alabama Blonde, our costume designer; our wonderful AD Nicolette Ellis, our post sound department, Alex Lee and Nicolas Pacheco, Kai’s camera team and the talented actors: Igor Grbesic, Ava Moslehi, Sedo Tossou, Savanah Joeckel and Luis Cadiz. And of course, Claudio Olachea, who was the second parent of the project every step of the way.

What can you tell us about any other filmmaking projects you’re currently working on or have coming up in the near future?

I am currently developing a comedic feature based on my experience in the army titled Unfit, an animated show based on my grandmother’s children’s book series and several other music videos which will be released soon!