Director John Stevenson has had a fascinating working trajectory. From his early-career days in the 1980s working as a story artist on Jim Henson productions Labyrinth, The Dark Crystal and The Great Muppet Caper, through to his 2008 Oscar-nominated directorial debut Kung Fu Panda, Stevenson has had his hands in many major studio projects. This makes his latest BAFTA nominated film Middle Watch all the more interesting, as it sees Stevenson return to a more concise and small-scale form of storytelling. The short film, which was made in collaboration with Falmouth University, follows a sailor in the latter days of World War II who finds himself trying to protect his delicate state of mind when he’s thrust in the presence of something extraordinary. Ahead of this year’s BAFTA ceremony, DN joined Stevenson for an in-depth conversation that covered everything from the lessons he’s learned over his extensive career to the existential heart of the story he wanted to tell with Middle Watch.

Where did Middle Watch begin as a project for you?

It began with my wife Carol, who got fed up with me being grumpy and depressed around the house after Sherlock Gnomes came out in 2018 and was a critical and commercial flop. She told me to make a short film to get my mind off it, to which my response at the time was something like, “That’s easy for you to say!”, but then the next day I found the story of Mr. J.D. Starkey on the web, and became intrigued. After a lot of detective work I eventually found the source of the story was a letter written to a magazine called Animals in 1963. With a bit of persistence, I managed to get three years of the magazine from Ebay and got my hands on the original magazine with the article. From there I started doing my research into the historical background at the Imperial War Museum, and The National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, researched the giant squid at the Natural History Museum in Kensington, they have a real one in their basement you can visit by appointment, and visited various art galleries to see the artists I had chosen as visual inspiration. Once I was stuffed with research I felt able to write my first attempt at the story and do the first storyboard. All that took from summer 2018 until autumn.

It’s a film about a man who goes through an extraordinary, almost-existential experience, how did you set out to tell that initially during pre-production?

The existential experience was the reason I wanted to make the film. The encounter with the giant squid was intriguing, but I was more interested in the question of what such an extraordinary event does to you. How are you changed by that? Is it a good thing, or a bad thing? In our story it is a giant squid, but it could have been a U.F.O., the Virgin Mary, or a unicorn. The thing I was fascinated by was how do you process something that is completely outside of your life experience. J.D. Starkey in his letter writes that he never told anybody about his encounter until he wrote to the magazine, some twenty years after the event. This is quite common, I found. A lot of people who have extraordinary experiences never tell anybody until many years later, for fear of being mocked or disbelieved. So what good was that unique event in your life if you keep it to yourself?

The thing I was fascinated by was how do you process something that is completely outside of your life experience.

These were the questions I explored as I shaped the story. Originally the ending was more negative, but as I worked on the film with Giles Healy, Aiesha Penwarden and Rob Strachan we all decided to make the encounter positive and cathartic, something not in the original letter. Aiesha had come up with the PTSD trauma, again, not in the original letter, and we decided to make the squid the catalyst to healing a psychic wound, to opening our protagonist up to a universe of infinite possibilities.

The film has next to no dialogue, was that the intention from the offset? How did that decision challenge you to present certain aspects of the narrative in a more visual manner?

The intention was always to have as little dialogue as possible, to embrace the challenge of trying to convey a man undergoing an enormous internal journey visually. Communicating the inner life of an artificial character without words is the hardest thing to do in animation but the most satisfying when you accomplish it and draw the audience in to fill in the blanks and come to their own conclusions based on their life experiences. Miyazaki is a master at this, and I had been completely enthralled when I first discovered his work back in 1984 when I saw Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and realised what was possible. I have always tried to give any of the characters in the projects I have worked on a rich, inner life, but Middle Watch was specifically created to be a short film about processing the unbelievable.

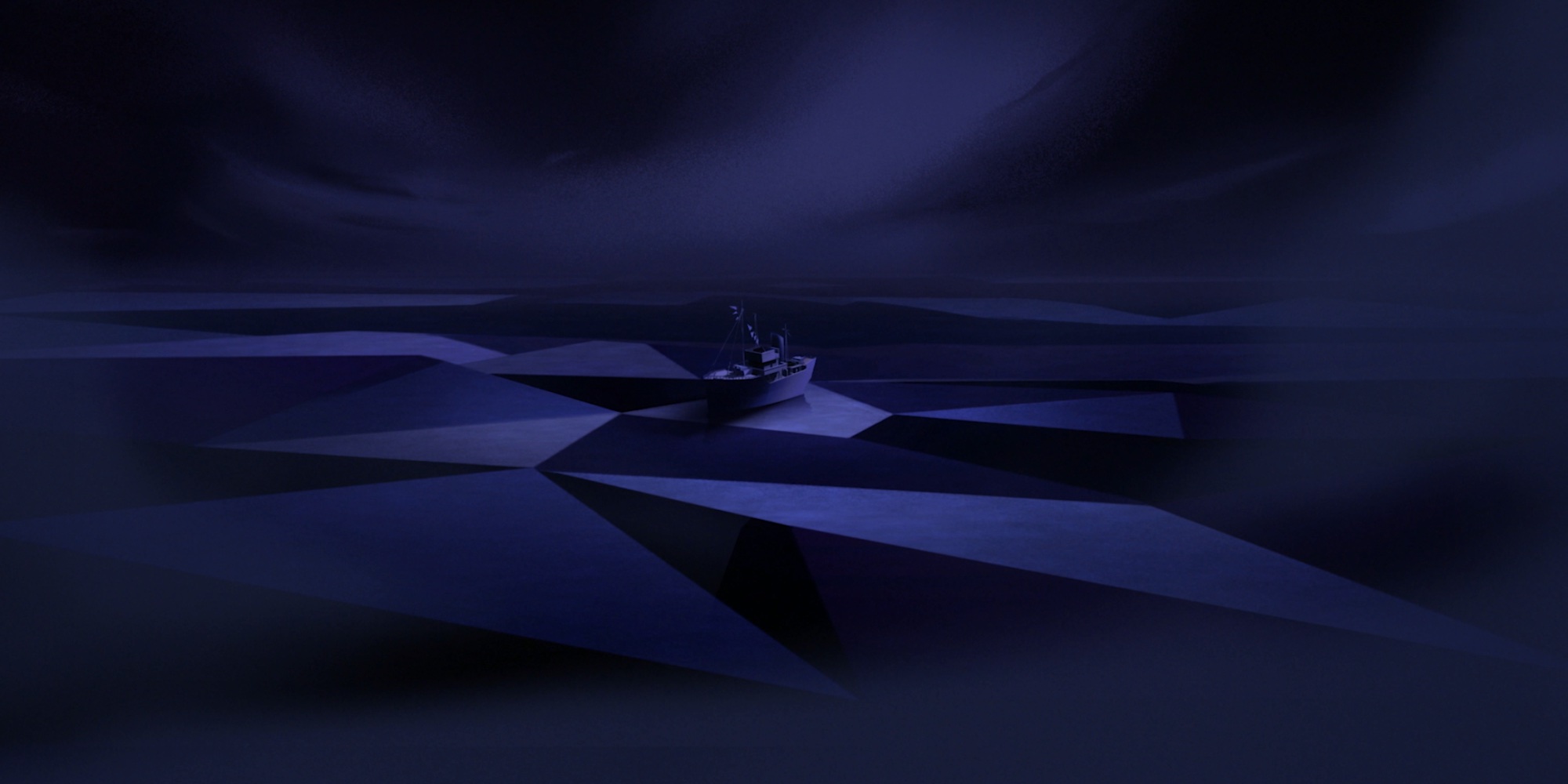

The line work and stylisation of Middle Watch is quite sharp and angular, what brought you to that approach?

Once I had finished my factual research on Middle Watch I started to think about a visual language for the film. I knew I wanted it to be in hand drawn animation, my first love, and I wanted it to have a very distinct style. As part of my historical research I was looking at the works of British war artists from the Second World War, and was very struck by their abstraction and stylisation, whilst depicting the truth of real events. I studied the works of Eric Ravilious, Barnett Freedman, John Everett, Paul Nash and others, and determined that trying to animate in a style inspired by their work would give the film a unique and appropriate look. I also hoped that if anybody understood the references we were drawing on the fact that these were war artists, tasked with telling the emotional truth of human experience in extreme circumstances, might add some integrity to the extraordinary event told in our film. The final animatable style was created first by Prawta Annez, and then refined by Aiesha Penwarden.

The film was made in collaboration with Falmouth University, what was their involvement in the production?

In the autumn of 2018 I had the basis for the film. I had completed my historical research and had collected photographs, books and reference materials to inform the design of the ship, the squid, the uniforms, equipment, etc. I had collected books on war artists to use as inspiration. I had written, and re-written the story and drawn my first storyboard. I had everything I needed to make the film, apart from people and money. My friend Derek Hayes, a lecturer at Falmouth University in Cornwall, had invited me down to give a talk to his animation students, and my oldest friend Jocelyn Stevenson, no relation, had wanted me to meet Giles Healy, who lived in Devon, a producer she liked and had worked with. I reached out to Giles and invited him to my lecture. After my talk, Derek, Giles, Carol and I went out to dinner and over a very good Thai meal I began to see a way that I could make my film, whilst hopefully adding value to the students’ education. I invited Giles to partner with me, and luckily for me he said yes. I proposed we approach Falmouth with the idea of making Middle Watch part of their curriculum for their students.

I have made many mistakes in my career, and mistakes are the best teachers in the world but am a quick study, so I tried to bring all the things I knew worked well to Middle Watch.

I have lectured at a lot of universities all over the world and however talented their students, or good the short films produced, the one thing that universities do not seem very good at doing is preparing their students to work in the professional industry. Making a film at film school is not the same as making a film in the real world. My proposal was to give the students at Falmouth real world training, making a film with a professional director and producer following an industry standard production pipeline and quality control, but without the pressure of a deadline. I hoped we could equip them to leave university fully prepared to enter the industry and to have a good understanding and expectation of what would be required of them.

Falmouth, and a little later Arts University Bournemouth, were gracious enough to see the benefits and agree to this idea, and Middle Watch became a voluntary project for students to work on if they wished. I brought in industry professionals I had worked with to provide masterclasses and critical feedback. It had to be a win, win situation. The win for me was getting my film made. The win for the students had to be getting access to high level talent and a real world understanding of what was expected when working on a professional project. I believe it was a success on both fronts.

Have you found that your work in feature filmmaking has informed your process in returning to the short film form?

I have been working in the industry since I was sixteen, almost fifty years now. Everything I have done, the good and the bad, from high level feature films to no budget commercials, has informed where I am now. All the experiences were learning opportunities, and some of the most negative experiences provided the most useful lessons. I have directed two animated features for major studios, and the sheer amount of work over many years dealing with hundreds of people definitely taught me a lot. I have made many mistakes in my career, and mistakes are the best teachers in the world but am a quick study, so I tried to bring all the things I knew worked well to Middle Watch, and to leave all the things that I knew to be unhelpful or harmful behind. I tried to make sure it was a positive experience for everyone, including me, and my belief is that anyone who worked on Middle Watch could go on to work on a big studio feature film and succeed. This is especially true of Aiesha Penwarden and Rob Strachan, who matured over the three years we worked on the film to become fine directors and leaders. I look forward to seeing the films that they make for themselves.

Who did you work with on the score? What were you looking for the film to evoke sonically?

Our music was done by Clarinet Factory, a group of four amazing musicians from Prague. I was introduced to them by my friend Ondrej Beranek, one of the owners of the wonderful Karel Zeman Museum there that I love to visit. Originally, Ondrej suggested that if we could use Czech musicians we might be able to get a little money to do our post production in Prague. Back then I had no knowledge of Clarinet Factory or the sort of music they made. Honestly, at that stage, if they had been a heavy metal band I would have said “yes” if it would have helped get the film made. Luckily when I heard their music, I was entranced. They have a completely otherworldly, unique sound they create by only using clarinets. I had never heard anything like it, and immediately it seemed like the perfect sound for our strange tale.

I honestly think their music is responsible for half the emotional impact of the film. I can not imagine Middle Watch now with any other kind of music. I did not know when I began that an all clarinet score would be the perfect music for our story, but in my experience, if you are lucky and have committed deeply, your film will tell you what it needs and draw those people to it. It needed Clarinet Factory.

What will you be working on next?

During the pandemic I wrote another maritime story based on real events from World War I. Giles and I are trying to produce this as a European hand drawn animated feature for adults. Working with Northern Ireland Screen we got a great script by Matt Harvey, and have a fantastic visual design based on the works of a famous Spanish graphic artist. Fingers crossed!