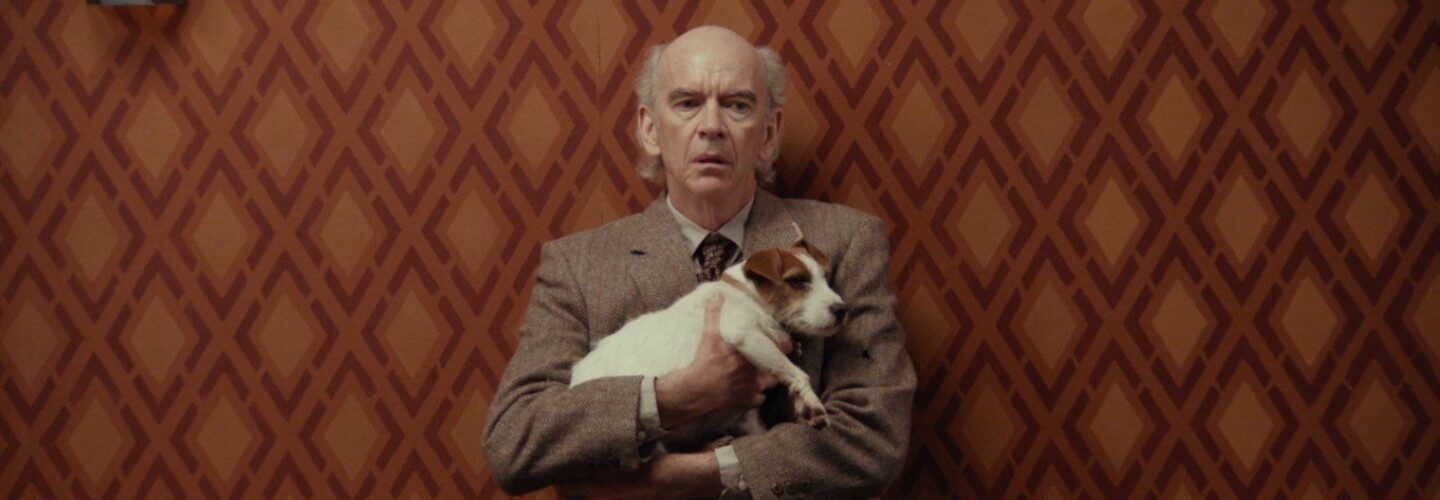

Modern day life may have seen the majority of us packed into cities, on top of each other, paying eye-wateringly expensive prices to live in ticky-tacky boxes but perhaps none to quite the same degree as the man and his dog in Seamus Murphy’s Henry Needs a New Home. A delightfully absurd short which was born of the Australian filmmaker’s own feelings of claustrophobia and disillusionment with overpriced accommodation. The film takes us on an absurdist, yet completely relatable journey through one man’s feelings of despair and eventual total disillusionment towards his life and living situation, ultimately forcing him to face the terrifying abyss of dealing with loss before gathering the determination to make a change and pick himself back up. Alongside pulling on your heartstrings Henry Needs a New Home delights with its considered and playful production design and frenetic montages depicting the chaos faced by our beleaguered protagonist. Ahead of his surrealist comedy premiering on Directors Notes today we spoke to Murphy about choosing to make the film entirely dialogue free, the power of his lead actor Nicholas Hope’s physical performance and designing the menacing metallic antagonist.

What were the roots of this delightfully absurd idea?

The initial idea came from a thought that I’m still not sure is a memory or my own conception, the thought related to what I believe was a children’s story in which there are fairies living inside a keyhole. After researching, I wasn’t able to find anything more, and the more I thought about the setting the more I thought that it would actually be extremely stressful living in a keyhole, especially if it was an active keyhole! So I started to build the story and plot around this initial premise and I liked the ideas and themes that emerged.

In the context of my own life, I was working a job I didn’t like and living in a very small and crappy apartment and paying a fair bit to do so. The system of capitalism, the nature of employment and money itself has always seemed strange and somewhat unfathomable to me and yet, like a lot of people, I have found myself in jobs that are extremely mentally and physically challenging. I think all these things probably played a part in the story coming together as it did.

The production design of Henry Needs a New Home is quirky and beautifully surreal, what was the process of constructing that environment?

Henry’s home was brought to life over five cold months in the backyard shed of our cinematographer’s house. The ten-metre-long and four-metre-wide house was made up of twenty custom steel framed flats and an expanse of discarded chipboard panels cut and painted to look like hardwood floorboards. Vintage wallpaper for a space so large was way out of our modest budget, so the art team set to work making two interlocking stencils which were used to create the intricate hand-painted tri-color pattern, the process took around four weeks and many helping hands.

To create a huge moveable prop out of a lightweight, rigid and cost effective material was a particularly unusual and tricky brief.

The key almost became a character in its own right during the pre-production process. Creating a huge moveable prop out of a lightweight, rigid and cost-effective material was a particularly unusual and tricky brief. Thankfully we had Frank Veldze, our amazing Head of Construction, who designed the key to be constructed from large pieces of polystyrene attached to a steel core. The nine-metre-long key was transported to set in four sections, glued together on-site and carefully attached to a forklift so it could be manually moved in and out of the set by a single person.

The stencils are reminiscent of the wallpaper from The Shining, was that a conscious decision?

We didn’t talk about The Shining as an influence for the walls, but I do love that film so perhaps it subconsciously got in there. The style of the walls in particular felt like a big decision and we went back and forth on different geometric patterns and colours. We wanted it to be Art Deco but also still homely. Barton Fink was a starting place for my conversations with Production Designer Celeste Veldze; she did a brilliant job with the walls, the key and everything else.

Why did you decide to make the film dialogue free?

It came about pretty organically. For the most part it’s a story about a man and a dog living in a single room so from that perspective there wasn’t any need for the Henry character to say anything. In scenes where I felt dialogue was perhaps needed, I just decided to commit to having no dialogue and figured out other ways to convey what was happening.

I wanted the visuals of the film to be strong and to largely tell the story.

This approach also tied in well with other aspects of the filmmaking. The protagonist was crafted specifically with Nicholas Hope in mind and I wanted the Henry character to have a really pronounced physicality, something like a Monsieur Hulot or Mr. Bean, and those characters I think are throwbacks to the silent era of film so they rarely speak. I wanted the visuals of the film to be strong and to largely tell the story. Sometimes I’ve found it beneficial to remove or minimise an element to give other elements a boost.

Henry’s mental and physical breakdown is so heartfelt. What was it about Nicholas Hope that made you want to write this part specifically for him and what was your process for developing his performance?

I first became aware of him when seeing his mesmerising performance in Bad Boy Bubby. From then, I kept noticing him in various things. He can do it all as an actor, but I think he’s particularly brilliant as a physical performer which is why I thought he’d be perfect for this film.

Grant Hardie, the director of Monster Fest, put in a good word to Nicholas and his agent for me. Nicholas read the script and other materials I’d put together and came on board. He’s based in Sydney and I’m in Melbourne so we didn’t meet in person until the shoot. We spoke a couple of times on the phone about the script and made sure we were on the same page with how we saw the film. During the shoot we would speak a little before each scene but nothing major – I mostly wanted to stay out of his way because I knew he’d read the script super thoroughly and with all his experience and skill I was confident in what he’d deliver. It was also so nice being surprised by what he would do when the camera was rolling; he would always add some nuance or detail and it just elevated every scene.

Cinematographer Jack Riddle chased Nicholas around the set like a possessed paparazzi and just captured as much of the destruction as he could.

The frenzied action of his world literally being shifted off its axis time and again is such fun to watch, what were the practicalities of filming those scenes?

We shot those scenes in a slightly chaotic way. I think that was half by design and half by necessity with how much time we had. I knew I wanted that section to be frenetic but also rhythmic. I had maybe ten things in the script I wanted to shoot for that section, some of which were thrown away for various reasons, and then on the day, we were all coming up with ideas just because it was so exciting being in that space and having Nicholas and Daisy (Henry’s trusty Jack Russell Terrier). For the scene where he is destroying all the furniture, that was just one long take broken up. Cinematographer Jack Riddle chased Nicholas around the set like a possessed paparazzi and just captured as much of the destruction as he could.

What cameras did you use to capture that pandemonium?

We used the Arri Alexa for the majority of the shoot. There are a couple insert shots taken on a Blackmagic Ursa and another few mounted shots taken with a GH5. We had three different lenses: a Cooke cinetal 25-250mm zoom, a Zeiss 16mm and a Kinoptic 9.8mm. We also used a Ronford F7 tripod head a couple times to get some wacky sideways tilt shots.

What will we see from you next?

I’m making a feature film. I’m currently finishing a script about a woman who loses her mother and experiences rapidly escalating levels of grief and melancholy… It’ll be surreal, but with dark comedy, too.