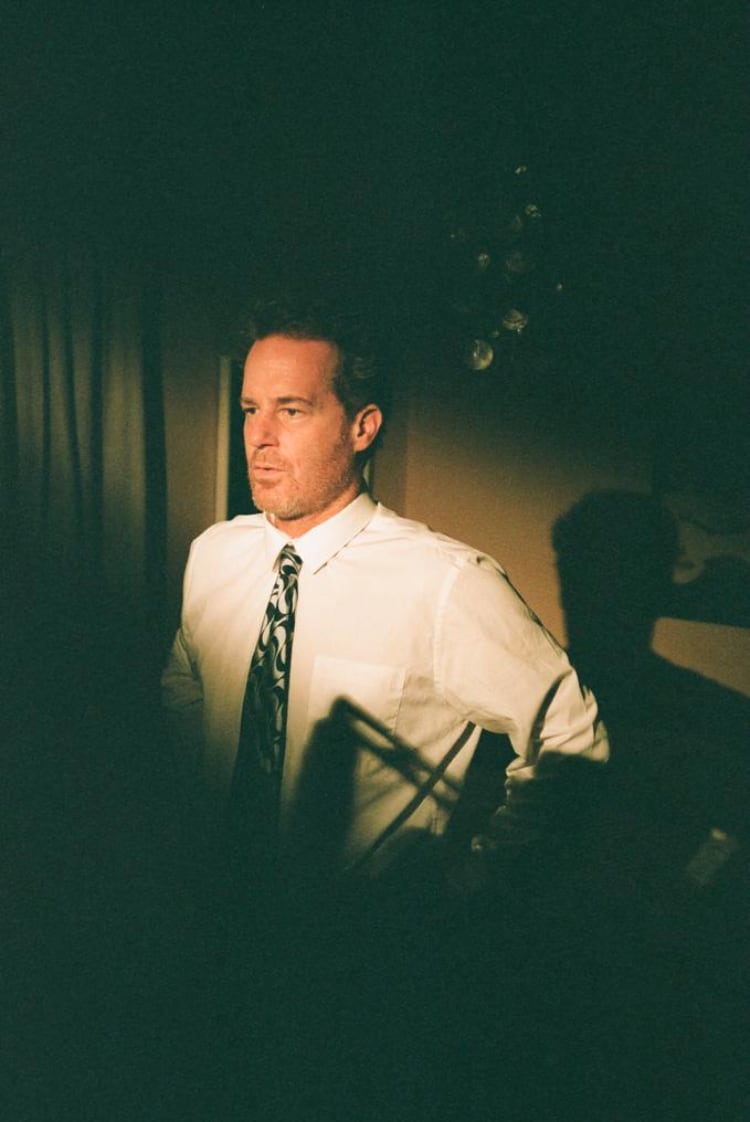

As many a therapist’s coach has witnessed, in favour of running day to day as a cohesive unit many a family opt for the (perhaps not healthiest) strategy of pushing the simmering tensions they hold against one another to the background. But what if there was a way for you to have a much need cathartic vent, free from the worry of hurting the feelings of those you hold dearest? Filmmaker Daniel Turvil may have found a possible solution with This Much, So Far, his short film about a suburban dad who gathers a stand in cast of life-like dolls so he can deliver a torrent of unflattering home truths to his kin. It’s a film that does a great job of deploying the talents of actor Adam James, whose frenzied performance of Turvil’s high concept script is just as terrifying as it is captivating. DN is happy to present the online premiere of This Much, So Far below, after which we speak to Turvil about his putting his protagonist centre stage throughout his domestic location, as well as his take on the medium of short films.

The writing encompasses a great mix of drama, comedy and a touch of horror. What inspired you to bring all of those elements together to talk about the spiralling of a middle class family man in suburbia?

There’s certainly no horror in it from my perspective, to me it’s just drama. I get that it’s funny but there wasn’t even a sprinkle of comedy in our approach. It was very serious. I really wasn’t thinking about genre. My short films are just formal exercises – they’re practice and, if you’re someone who wants to make feature length films, they’re calling cards. Not necessarily direct antecedents of your feature work but, I see them as a place to play around and make mistakes and just figure out the process of making a film.

To be honest, I don’t really see a place for genre in short films. Seems crazy to me. I don’t think they need to be categorised in that way. In saying that, they’ve only started having genres for like the last ten years in this big way that we see now. It’s a funny thing. It’s an institution now; the short film. And I don’t necessarily think that’s a good thing because it encourages people to think small. There aren’t any dream big posters out there. I think shorts are being too highly celebrated, it’s all too serious for me and I don’t understand it.

I get that it’s funny but there wasn’t even a sprinkle of comedy in our approach. It was very serious.

I was inspired by the people of the suburbs. And the trees. They’re so cool and they all have brains. People walk around in circles there. Simpatico with their dogs and children. It’s like riding a bike into a brick wall over and over again. It’s awesome. But there’s an end… The end! So, there’s a purpose but it’s strange. I used to try and force myself to get lost on the way home but some unknown force would always propel me back in the right direction. I think it’s the spiral. Like one of those claw grab machines but for people. And you win every time but the prize is your own life, every day. So you have to come to terms with that.

The dramatic staging throughout the house of his confrontations work really well, was this all preplanned or more discovered once you were in the space?

Planned like Nan’s 90th birthday BBQ! The house was very important. We were looking more at American architecture. I love American suburbia. In the UK, our suburbs are pretty lame. They’re just pretty grey and stuff. But this house had that ‘dollhouse’ kind of feel to it, it also needed to be quite big. We were asking each other how we could make it look like a stage without actually having one so it was the opposite, really. We wanted it to look staged, not to create the illusion that it isn’t, so it was backwards in that way. I love Douglas Sirk and Hitchcock and Nicholas Ray and William Wyler – especially as they’ve all made great films in suburban houses like: The Desperate Hours, Bigger Than Life, Shadow Of A Doubt and All That Heaven Allows.

I viewed the whole thing as him having a psychotic episode for twenty minutes. The family are all real to him in these moments, he’s detached from reality.

And of course your lighting is a big part of that staged look too.

The whole staged element is intended as irony, really. It’s funny only to me in that way. It’s cathartic for the character but it’s stupid that it is. It’s completely regressive and shrouded in delusion, no puzzle has been solved. So, those elements are all there to accentuate how backward this guy is. The spotlight is, quite literally, on him but he’s preaching to an invisible choir. I think we could all probably do that. That’s what it’s like to be in one’s own head…or house for that matter!

Adam James’ blistering delivery draws you right in. How did you two work together to create that solo performance?

I guess I just put a bunch of ideas in a cauldron for him and then just said, “Take it away”. I was really confident in him and the script was pretty detailed. We spoke about the character but I wanted to keep it simple. I feel like the dialogue is so loaded that it was easy to read between the lines. I viewed the whole thing as him having a psychotic episode for twenty minutes. The family are all real to him in these moments, he’s detached from reality. So, the derangement of it all — I hoped — would be enough for people. I guess you worry now because the attention span of the modern consumer is about ten seconds but, it was Adam who made the performance so captivating, it’s a testament to his talent.

I feel like the dialogue is so loaded that it was easy to read between the lines

I also showed him Michael Redgrave’s performance in Dead Of Night and asked him to watch Days Of Wine And Roses. Having seen him in Dario Argento’s Mother Of Tears and other stuff, I knew what he could bring. He’s also done lots of theatre, so he was the perfect double threat. He’s a great actor and it was really cool that he came on board.

I also wanted to ask about the art, there are some really cool pieces around the house. Were they made for the film and do they hold any particular significance?

Yeah! The art was done by some good friends. David Harkins who is a great Brighton-based painter. He is awesome and his art has this sort of potent ambiguity which is just beautiful. And then Ketan Jandoo, a local legend of the underworld art scene and one of my best friends. The Bacon-esque stuff is done by this guy called Steve. He painted these pictures of his friends who had died and stuff, one’s a self-portrait he did when he was all tripped out. He’s a very cool person. But none of the art was made for the movie, it existed already. It just worked.

What’s next for you as a filmmaker?

I’m working on a shot-for-shot remake of Gus Van Sant’s Psycho.