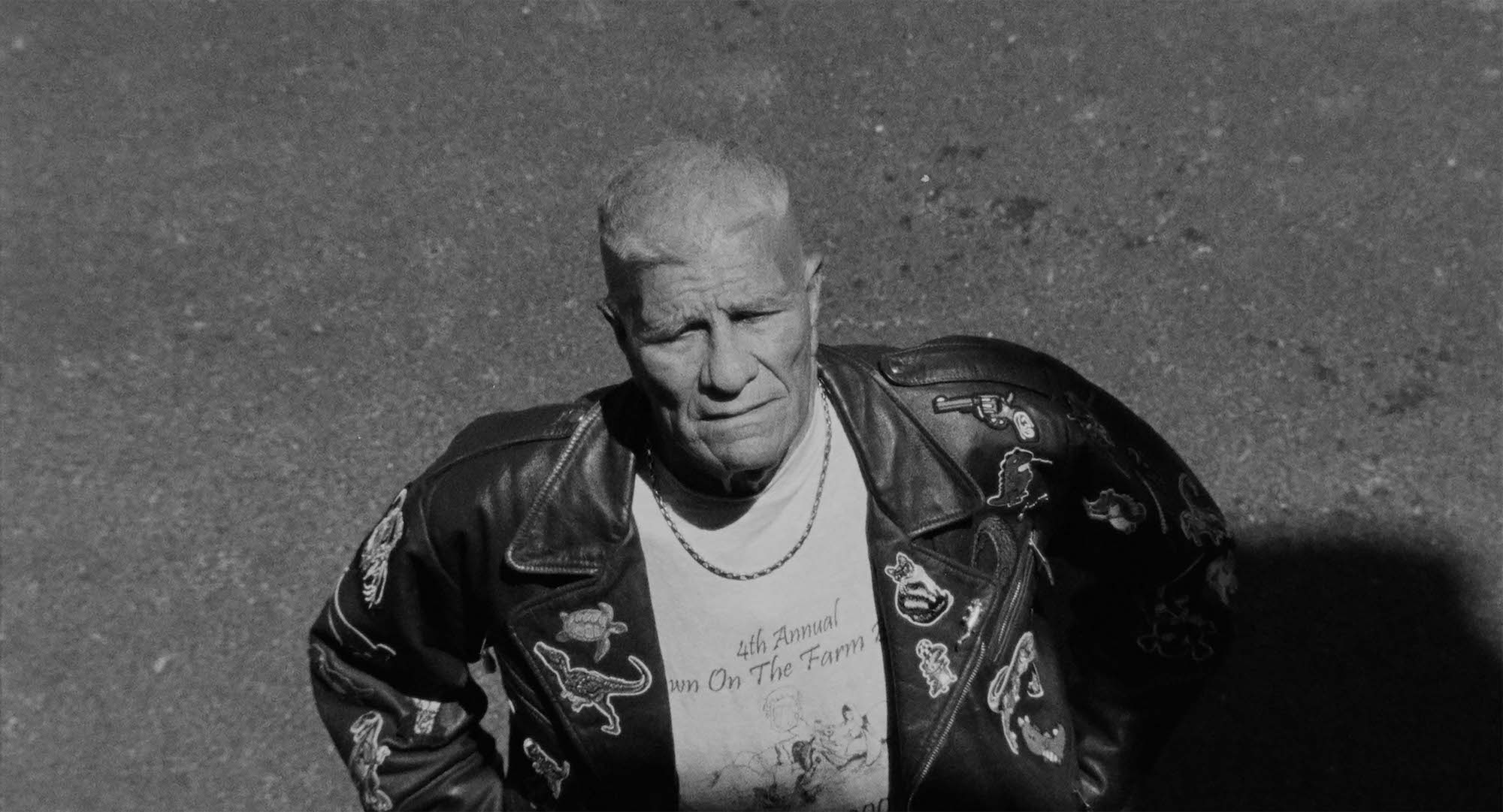

For all the bands that finally make it and become superstars, there are perfectly wonderful groups that languish in obscurity, endlessly travelling the country in search of a willing crowd. For the post-punk/new wave band Gwendoline, lending themselves excellently to Joaquim Bayle’s eponymous film, this is something that they can certainly relate with. Making a transition from commercial work to a more esoterical form, Bayle creates a variety of deadpan situations, allowing rural French locations and 16mm black and white cinematography to create a truly timeless feel. With shades of French New Wave as well as Beatles films, this is a truly delightful short that will resonate with anyone struggling with recognition for their creativity. We invited Bayle to join us for a conversation about relating to the band’s struggle, casting them as a fictional version of themselves and why prepping a film is often the most fun part of the filmmaking process.

Tell me about how you got in touch with Gwendoline and decided to work on a film together.

I found out about this re-published album and I was immediately intrigued by it. Above all, I felt their music was directly speaking to me at that time since I was in this kind of situation, like a lot of people I guess, where you are starving to create but you feel restricted by different things so I guess the decay of Gwendoline’s music and their disillusioned situation while creating this album might have resonated with my frustration at that time. Within the week I talked to my friend and Producer Alix about this musical discovery without really having any ideas about what we could do with Gwendoline but we eventually set up a phone call with Pierre and Micka from the band and their manager Flo.

Basically, I was talking for 30 minutes straight about the stuff I loved from their project, the fact that it feels honest because they have been composing and creating this album without big stakes or trying to seduce anyone and ticking any boxes. To me it clearly felt like a personal, cathartic and completely free creation with a good amount of self-mockery and humour, which is something that gets my attention most of the time with any piece of art. We wrapped up the phone call without any precise idea of what would be next and a week later I had a first draft of a script for a narrative short starring Pierre and Micka as the main protagonists and with live performances of the band. A few days later Pierre and Micka got back to us and without any doubts, even though they had never acted in films before, they said something like: “This feels personal, let’s do it!”.

I guess the decay of Gwendoline’s music and their disillusioned situation while creating this album might have resonated with my frustration at that time.

I love their post-punk sound as well as the nonsensical yet somehow rather evocative lyrics. Did you use these lyrics as an inspiration for the film?

I guess the lyrics infused inside me after a certain time listening to their music but during the writing process, I actually tried to not take or do anything that relates or matches heavily with the lyrics or with the subtext of it. I find that Gwendoline’s lyrics are so sharp and, in my opinion, so spot-on in picturing some of the absurdity of life and some social behaviours it didn’t need more context. Unconsciously some scenes in the film match with the dramatic tone and rhythm of the songs but I don’t think it is too much connected to the subtext of the lyrics. In the end, I perhaps used the lyrics as inspiration for the writing process to have a better understanding of what Pierre and Micka’s sensibilities could be as human beings.

In many ways, it’s a classic band film that reminded me of The Beatles, especially with their haircuts. Were there any films in particular that you took inspiration from?

It’s not one film in particular but mostly the strong universes of some writers/directors which strike a chord in me from the surrealism of Buñuel and Fellini to the experimental and singular editing of Godard as well as the deadpan style of Kaurismäki. Nothing too contemporary I guess… Regarding the “classic band film” aspect of it, to be honest I was mostly interested in setting a classic theatrical structure and then playing and messing around with an experimental twist and trying to write unexpected scenes to create both awkward and poetic situations. In the end, the film might spin the viewer on their head but I don’t think people will leave the theatre at festivals either because it’s a really simple story to follow.

Were they experienced with acting before? I enjoyed the deadpan vibe the film operates on. Did you rehearse scenes in order to get a particular effect?

The film has a wild mix of actors, non-professionals, friends and technicians in the cast. I really enjoyed the variety of profiles with professionals and amateurs. I hadn’t any other choices anyway which is a good thing for a first film, to be able to build with what you have and maybe try to keep doing it that way on the next ones. For Micka and Pierre, it was their first time acting and even though it was new to them and the style of the film is quite specific, they were the first ones to give up on their fear of how they would be represented on screen.

The fact they had no professional acting habits was actually really nice because I didn’t want them to ‘act’. I was more interested in their silence and the personal twist they could add to the neutral characters on the page. During the prep we took a bit of time to do script reading but also to simply spend some time together and a day prior to the shoot we rehearsed some of the scenes but it was quite loose even though the tone and the mise-en-scène were really controlled. The deadpan style on which the film operates is coming from the situation the characters are in. And the time we spent in these awkward situations and the distance the camera is from these situations flatten the dramaturgy.

The fact they had no professional acting habits was actually really nice because I didn’t want them to ‘act’.

I loved the use of black and white, which seems to evoke classic French movies, from the New Wave to Renoir. Did you always want to use black and white? What does it achieve here?

We shot on colour negative while monitoring a black and white image. It was a stylistic desire which we had from the very beginning with my Cinematographer Angelo Marques. To me, it was a way to be able to conceive the black comedy tone with this idea that it will emphasise the existential quest of the characters as well. I also had in mind this pure black and white comic book sketches style that I wanted the film to incorporate to strip it down to only the necessary. I like how radical the black and white feels and I can see myself or anyone discovering the film in a few years from now and still being OK with the tone and the look of the short. The black and white enables me to work on an empty canvas where there is no longer any question of temporality and reality, but it also allows me to impose a theatricality on which comedy and absurd situations will be able to spread.

The black and white enables me to work on an empty canvas where there is no longer any question of temporality and reality.

You also shoot on 16mm. Which camera did you use for this, and what advantages does film have?

We shot in a Super 16mm film format with a French Aaton (XTR) camera. The only thing that I kept saying to myself from the beginning to the end during the creative process is that I wanted to craft this film as a dark fairytale about the elegance of despair. Using the magical quality and rich texture of the S16mm film format felt the right fit to bring this feeling and spirit to life. It really started to be interesting and helpful technically and creatively when it was paired with our short film production scale. It gave us some simple strict rules to follow: a limited number of takes and no classical coverage. These constraints allow us to create a singular form where the film will organically answer to its own pressures.

The locations feel like they could be any era from the 1960s onwards. What was it like looking for the right places? Was there a long location-scouting process?

I wanted the film to take part in the countryside of France for many reasons. Formally, I wanted to portray vast and modest landscapes to give a lot of space for the viewers to explore the frames. But also for production reasons, shooting in the countryside was way easier than in the city. We had more freedom and the experience of shooting felt more interesting overall. We spent the time off with the crew and technicians all together instead of everyone going home after each day. I don’t know but it feels closer to a better experience. So I had typical locations in mind when I first wrote the script – locations you could find in any small town in France – and my Producer Alix had some of his family members living in a traditional province of France (in Touraine).

I love the scouting process. It is perhaps my favourite thing to do in prep.

After a first visit there and because we could have some connections with some locals to get a few locations fairly easily it felt completely obvious to decide to shoot the film in that region. I love the scouting process. It is perhaps my favourite thing to do in prep and for this one, we went several times there since it’s about two to three hours from Paris. We dug for stuff that felt at the same time completely mundane and unique. It’s a contradiction that I think lifted the art direction of the film, while we didn’t bother much about coherency since the black and white helped us there.

What was it like making the move from commercial films to a personal project like this? How much was similar and how much was different?

To me it felt liberating, since as a commercial film director what we are asked most of the time in commercials is to be ‘seductive’ on how we conceive the films, it’s a lot about compromising, being not too radical, etc. But here I went the opposite way and really the connection with my commercial work isn’t obvious. It’s like when I write a personal project I am rejecting everything from what I do and learn from the commercial world. Instead, I am looking for inner truth and a sort of weakness to expose on screen. In that sense, it’s quite different from doing commercials.

In the meantime, this liberating move wasn’t easy. In France, it isn’t like in the US where people or decision makers don’t really understand that you could have both hats: be a creative and a film director in the commercial industry and write and direct narrative/personal work at the same time. It’s like there aren’t any nuances. But I never really understood that or wanted to comply with that idea and stick to one ‘label’. I want to do both things the best I can. If we are looking at some of the most interesting artists, like Magritte for example, he started by doing commissioned works before his more personal paintings were being recognised.

To me it’s the best thing to do in order to gain experiences and to learn more, to meet other creatives and skilled technicians; all of that to escape perhaps some of the frustrations you have when writing alone every day while waiting for grants that will never come or waiting to find the right producer for your next narrative project. It helps to balance that everyday filmmaking hassle even though doing commercials can really be nerve-wracking as well with all the bullshit that surrounds it.

To me, Gwendoline is very much a film about perseverance in the face of dwindling success. Does Gwendoline’s story vibe with you as an artist?

Yes, I feel that too and to a larger scope the film by its simple setup (the band performing in front of an audience) is about self-expression through art and its inherent battle: a confrontation between two things, the desire to connect with the world and the refusal of all links. This ambiguous and contradictory emotion is what art should contain in its core radical expression even if people reject it. I think what really touched me in Gwendoline’s story is the creative outcome resulting from the despair the band had at that time and how they transcend that feeling to create something completely singular, poetic and honest. I can totally relate to that as a filmmaker.

What are you working on next?

There are many things in the process right now for me. With my associates and friends, we just started a production company called Pral: a multidisciplinary production company based in Paris focusing on commercials, cinema and curating events and screenings.

I am also working on a second short film which we are trying to produce this summer with my Producer Alix. Regarding commissioned works, I’m continuing to answer and pitch to agencies for commercials while also doing a long-term project this year with Carhartt WIP. It’s a special project we shot entirely in the US documenting their skateboarding team which should be released at the end of the year.