The small rural islands of Kinmen, part of Taiwan but within swimming distance of China, has long held its own as a spot as a hotbed of political conflict and escalating tension between the two countries and is closely examined through the eyes of documentarian S. Leo Chiang in his Oscar nominated short Island in Between. This film is by no means a singular or straightforward observational look at the islands’ historical and political significance instead, Chiang uses the islands as a metaphorical insight into his own sense of identity and belonging, split between his Taiwanese heritage and American citizenship which adds to the profundity of this filmic exploration. Kinmen holds mythical proportions in the imagination of the public and has also been a place of resistance against the overbearing desires of China, and Chiang with a mix of archival imagery, narration and heartfelt familial connections, offers us a brief but tantalising glimpse of the significance of this scenically stunning part of the world. DN invited Chiang to discuss his concerns about making the film too American-centric and not open enough to the rest of the world, his evolving style as a documentarian moving from a more observational approach to first person narration and the rewarding universal connection he has received from people after watching Island in Between.

This has been one of the most interesting documentaries that I’ve researched as part of Directors Notes’ Oscar coverage because, admittedly, my knowledge and understanding of everything was so minute yet I am now fascinated. Please tell us a little bit about your film, Island in Between.

It is about this small Taiwanese outer island of Kinmen which happens to be literally within swimming distance of mainland China. So it’s a very fascinating place. It’s a place that’s really stuck in between if you will. It’s a place that I became fascinated with and realized that I as a person and my background as somebody who was born and raised in Taiwan and grew up in the US had a lot in common with this place. So that’s why I decided to tell the story.

That search for identity and belonging really shines through in this film, how did you broach that personal journey so delicately?

Taiwan has had this really interesting relationship with the US. The Taiwanese government, which initially was the losing party of the Chinese Civil War and forced to move to Taiwan, were able to survive because of the support of the US. As a child growing up in Taiwan, the US had an outsized role in our consumption of pop culture and our imagination. It was a place that people aspired to go to, either to travel to as my parents did or to move there. I moved to the US at age 15. It’s not all that unusual, there are many others like me, who are what I would describe as transnational. I’m a dual citizen of both Taiwan and the US so I see Taiwan and the situation from both of these lenses.

You knew about the Island because of your father’s military service but had it held any other type of special interest for you?

Kinmen Island has this mythical place in the Taiwanese imagination. We hear a lot of stories about Kinmen but few of us have actually ever traveled there. The stories that we hear tend to be some version of a horror because they tend to be told by young men who are forced to go there as conscripts to serve out their military duties. They are generally unhappy because they’re separated from their family and might worry about their safety because they’re there to fight against who we were taught to be our greatest enemy – the communists in China, right. When they come back, the story they tell is not about the beautiful scenery or the nature or the architecture, they’re talking about the fear that they lived in, the inconveniences that they experienced. But at the same time, because it is this unknown place we’re curious, and we want to find out more. For me, there was never really a clear reason to visit until my parents and I went there for the first time four years ago.

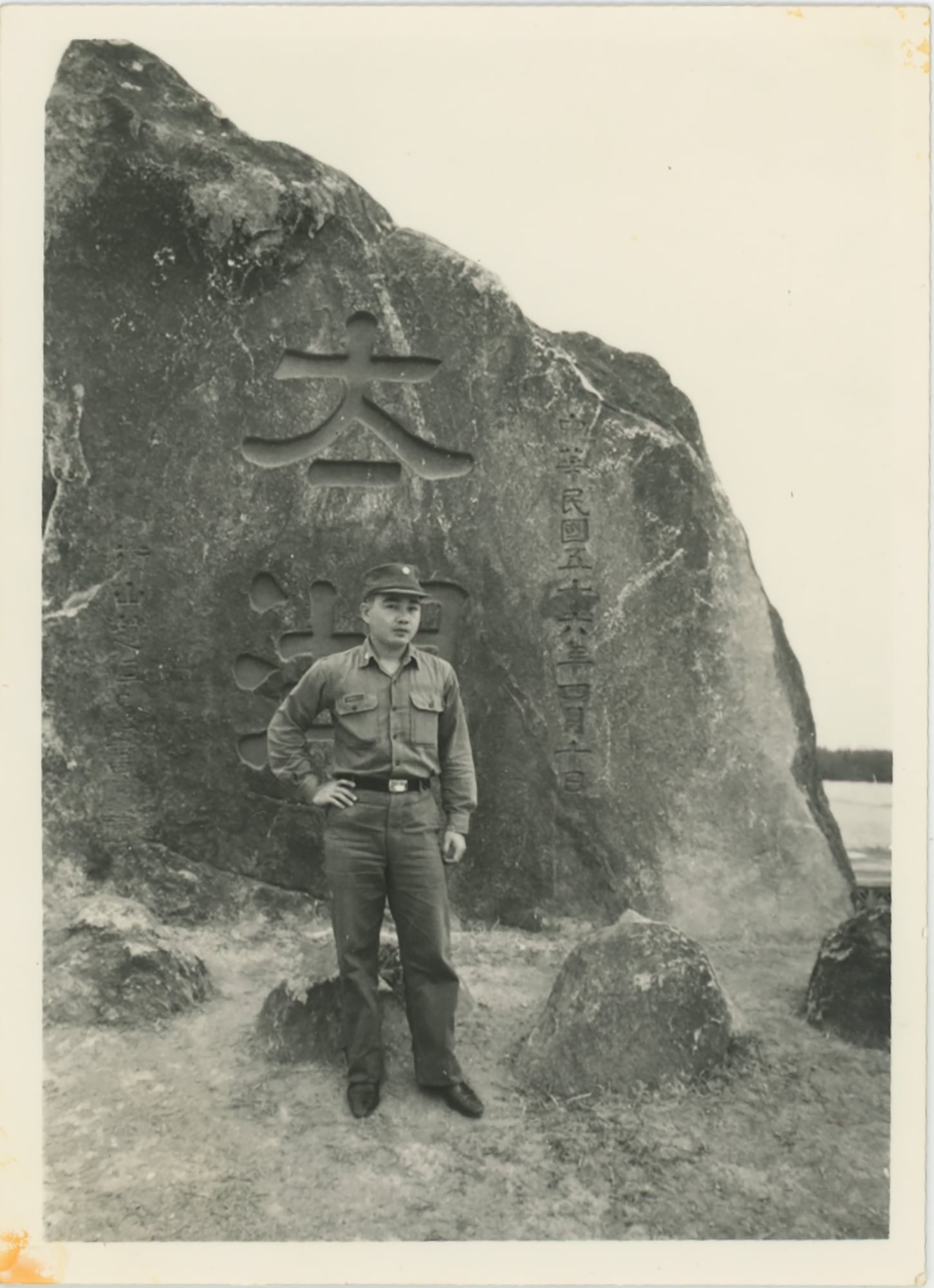

Funnily enough, because it was in the beginning of the pandemic and international travel was impossible there were domestic places that we had not been to, such as Kinmen, that we could go visit. I went with my parents. My father wanted to go to certain places he had not seen in literally 60 years and he wanted to see what it looks like now so I saw the island through his point of view. Through my own eyes, I observed the fascinating mix of military artefacts, natural beauty and traditional architecture. And the people, who have this really interesting existence to them that feels perfectly normal even though they’re not quite one or the other, really resonated for me. That’s how I feel when I’m both in Taiwan and in the US. When I’m in the US they consider me an Asian person and when I’m in Taiwan I’m told I speak and act like an American.

Was it on that visit with your parents that you knew it would be the subject for a documentary?

I didn’t quite know what or how, but I knew that I wanted to do something there. I was lucky enough to partner with a production company here in Taipei called CNEX who are quite well known internationally as the entity that supports a lot of Chinese language work for the international audience. We had a rough idea of what the film was going to be and I met a lot of the crew who would be involved in the film. In some ways it was smooth, but we really struggled to figure out exactly what the narrative would be. Initially, I didn’t necessarily think that I was going to be in the film. My motivation was my interest but that doesn’t mean that I should put myself in it. As time went on it became clear that my point of view was needed, especially for targeting. We wanted to tell a Taiwanese story for an international audience. I somewhat act as a guide or a cultural translator to put this really unusual place in context for the audiences outside of the region so they can better relate or connect.

The people, who have this really interesting existence to them that feels perfectly normal even though they’re not quite one or not quite the other, really resonated for me.

You mentioned the idea of examination of identity. I knew that those who might not be interested or might not know very much about Taiwan, certainly not Kinmen, would relate to this examination of identity. So it was a lot of those decisions, a lot of struggles in terms of trying to achieve the right balance of having the historical elements and the geopolitical facts, versus the personal, emotional thread that ultimately holds it together. So, yeah, you know, it’s somewhat a typical documentary journey, putting together the right tone and the right shape for the final piece.

That balance hit the right spot for me as a viewer not having a comprehensive understanding on the history of Kinmen but I found myself engrossed.

I’m very happy to hear that because we’re not trying to be the definitive film for Kinmen or for Taiwan. I wanted to offer a glimpse into the lived experience of the Taiwanese people, whilst I use my family and myself, in many ways our experience is actually archetypal. There are many other young men who served in Kinmen, like my father did, and even today they’re still there. The young veteran you meet in the film is from Kimmen, but he also served there. We wanted to spark some curiosity so you would go off and do your own research to learn a little bit more about it.

The honest truth is we live in Taiwan right now and I know from the outside, you hear all these stories about how tensions are escalating. So, people might imagine that it would be nerve-wracking to live here. But for us, we carry on with our lives – it feels perfectly normal. But should something happen I think that folks are more likely to sympathize and empathize if they already know us and feel they can relate to us. We’re a small island on the other side of the world and I tried to make sure their voices are heard and they have a bit of exposure – that’s definitely one of the intentions of this film.

It was a lot of those decisions, a lot of struggles in terms of trying to achieve the right balance of having the historical elements and the geopolitical facts, versus the personal, emotional thread that ultimately holds it together.

How did you find the reaction of the locals of Kinmen to you making this documentary and speaking to them about life there?

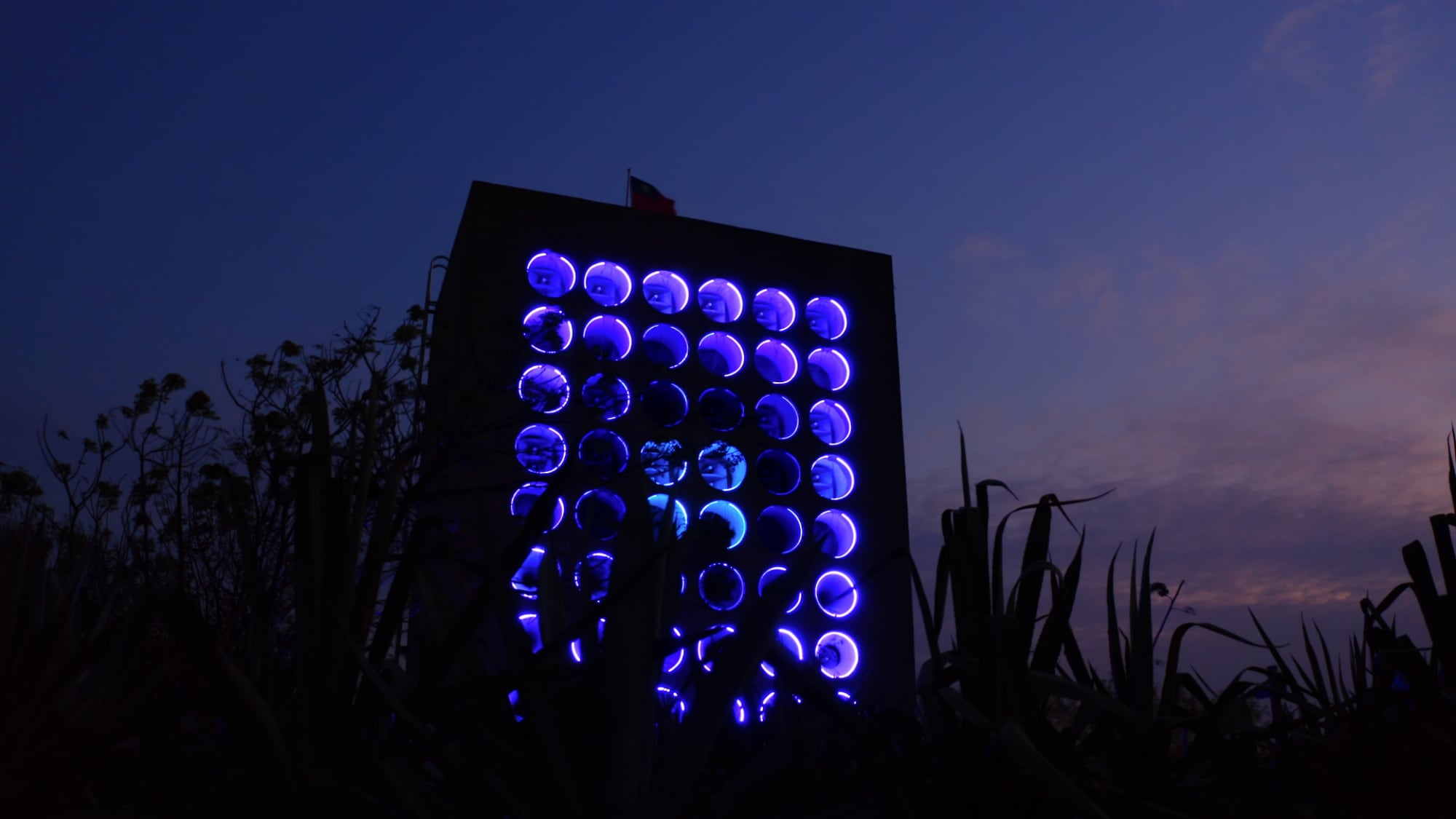

I don’t think anybody was surprised because there had already been members of the international journalism community covering the Taiwan Strait who inevitably ended up in Kinmen because visually it’s so representative and so powerful. That tank on the beach, those old bunkers and that broadcast wall. A picture tells a thousand words which is exactly what those images are. Folks are used to outsiders coming in and wanting to ask them questions and whatnot. So some folks were really happy to share. I’ve definitely encountered folks who weren’t as comfortable and a little worried about saying something that could get them in trouble. But generally, I encountered folks who are very forthcoming and very willing to share their experiences and their opinions about what’s happening.

Ultimately, we really wanted our focus to be from a personal lens. We didn’t want to spend too much time talking about the geopolitical situation and when we did, it was through my family’s story. I’m not an expert, I’m just sharing my experience. I’ve done my research as good documentarians do, but I’m not a scholar. I have not studied this place for years so my opinions and thoughts about this place are quite rudimentary and anecdotal. But I think that the emotional response is something that’s very relatable, so that’s what we ended up focusing on.

You’ve got some great archival footage in the film, was there lots available to you and how did you decide what to include?

Any documentarian will tell you that exposition and the backstory of any film and themes are always the trickiest because you don’t want to seem like you’re lecturing to people or giving them a history lesson. It’s quite boring when somebody just talks at you and gives you facts and stats so it’s all about finding just the right concise nuggets of information. Then, in combination, it serves as the foundation for you to understand the rest of the film. We were lucky to find some that I thought was quite fascinating. Funnily enough, a lot of the stuff that we found, especially the military history, came from the American military. They were so involved during that time and I was able to find propaganda films made for the American military or newsreels which I’m sure were consumed in the 60s when they were played in front of a film screening. I really enjoy discovering those and I found it interesting what was said and how it was framed.

I was able to find propaganda films made for the American military or newsreels which I’m sure were consumed in the 60s when they were played in front of a film.

I was always aware that I wanted to make this film not just for the American audience outside of the region but relatable for the rest of the world. There was this constant concern that I was making it too American-centric, even though clearly that relationship was central because of who I am and because Taiwanese history is so integrated. Maybe because of Ukraine and what’s happening in the rest of the world but I wanted people to see parallels in these situations.

You narrated the film yourself, we have archival footage, the narration and several other elements to create the film’s narrative arc. How was that process?

My body of work has been pretty observational-centric, I tend to love finding a great character, going on a journey with them, following them for over a long period of time and trying to use very little interviews. That’s been my aspirational style for documentaries that I love myself and I strive to do. As of late I’ve been really thinking about growing more as a filmmaker and being in this new phase in my life. Having been an immigrant in the US for a long time, but finally making a decision to spend more time and to move my base back to Taiwan. I feel like I have new relationships and new goals to set both personally and professionally and I wanted to give this first person style a try. We actually ended up working with a fantastic writing consultant who’s a documentary editor based in New York, David Teague, who’s done a lot. He happens to be an acquaintance and a friend of one of our producers and so was willing to come on board. It was a fantastic relationship and I always joke that he’s my narration therapist.

I needed to be able to clearly articulate the reasons, the focus and nucleus of my intention which then became the motivation for my narration in the film.

I think naively when you write narration you just go in and write about the subject matter. But the way he approached it, was to give me a bunch of writing prompts about my passions, my fears, my upbringing and my goals which is very existential. I understood what he was trying to do and I think an effective narration has to come from you and has to tease out why you’re making this film. Out of all the subjects in the world, even all the topics in Taiwan, why this? Why now? I needed to be able to clearly articulate the reasons, the focus and nucleus of my intention which then became the motivation for my narration in the film. There wasn’t that much but it took a long time to do. There was a lot of tweaking and adjusting and selecting the right word and using just the right example not to give too much but to trust the audience and our common experience as fellow human beings. I know that sounds a little grandiose but I really do believe that ultimately, documentarians are trying to construct moments where you resonate, you echo and people understand what you’re trying to say.

Obviously, we have to talk about your Oscar nomination. Do you think that has come from this being a subject matter that has just resonated with people?

I think we had fortunate timing. We ended up with a fantastic partner in New York Times Op-Docs which is so exciting for me as a documentarian to see these shorts platforms like The Guardian, Op-Docs and The New York Times with this massive audience that honors the short form. That’s exactly what the short form is built for, platforms like these and because we were able to partner with them and they were able to launch it right a month before the Taiwanese presidential election this past January. There was a lot of interest in writing more about Taiwan and learning more about Taiwan so we hit right at that sweet spot and folks responded to it. I was definitely getting a lot of emails from all over the world which has been very satisfying and makes me feel very happy to read some of those comments. You know, I remember reading something about a Cuban who lives in Miami and I totally understood their story. Korean audience members are saying they totally understand this story which is what we strive for.

I hope that people see that the film is advocating for a more complex understanding. Less about taking sides, more about empathy. The world is not black and white, it’s everything in between. Again, maybe I’m naive, but I really believe that if you can just convince folks to think that way, the world would be a much better place. Maybe the film spoke to folks who are horrified by what they’re seeing in the news and maybe they found some solace. Even though it’s a melancholic film, I hope that I’m trying to instil more faith in humanity and that comes through.

So what are you working on next, another short?

I would like to, but I actually am doing another personal film right now. It’s a feature length, maybe it’ll change. I’m being very open, it’s a film about my personal immigration experience to the U.S. I moved there as a 15-year-old without my parents. I think it’s an excuse to use a very personal angle to talk about Taiwan and the Taiwanese relationship with the rest of the world. I hope that it’s both emotional, but also informative from a sort of geopolitical perspective. I’m still fairly early on and I’m fully committed to taking more experimental approaches with this so we’ll see what happens. It’s a little scary, but, you know, it’s also very exciting.