Two skiers are suspended in space and time as the frozen winterscape of the Yukon Territory awakens their souls. This is the premise for filmmaker Cameron Thuman’s unique short Suspended in Time which blends narrative and documentary to tell a story of two individuals and the majesty of the environment they find themselves in. Thuman captures his skiers through dynamic aerial photography that is exhilarating one moment, then still and meditative the next. It really is a celebration of a stunning landscape through the eyes of those experiencing it in the most adventurous way possible. We’re delighted to be sharing Suspended in Space with DN’s audience today in conjunction with a conversation with Thuman who breaks down the unorthodox approach of making his short, the rendering of the film’s haunting blue palette, and the blending of soaring aerial photography with moments of character-driven interiority.

When was the idea of a film about the Yukon presented to you and what were your initial thoughts on how to tackle it?

NativeFour and I were given an open brief about making a film on the Yukon. I first thought it was going to be a documentary. I connected with our partners and learned many beautiful stories but was met with writer’s block. Nothing jumped off the page, telling me, “This is the movie.”

I pivoted away from a documentary. Rather than trying to find a pre-existing story, I shifted to learning about the sensations of the Yukon Territory. I talked to locals and had them describe the land: what you see, what you hear, how it makes you feel, etc. Everything started to click. I decided to make the Yukon the main character and place two first-time visitors into the world; we would see the land through their eyes. I fell in love with the idea of the Yukon ‘pausing time’ during these initial calls. I imagined an art house lens paired with an expedition narrative.

I decided to make the Yukon the main character and place two first-time visitors into the world; we would see the land through their eyes.

Was it then a case of penning the screenplay and sourcing your cast?

I wrote the screenplay and the final script turned out to be five pages, encompassing 18 scenes. We had an extensive search to find the right talent. I wasn’t just looking for skiers; I needed to find a cast that could also ‘sell’ the scenes. The only way to do this was if they were already friends for on-screen chemistry and came from different parts of the world to share their unique POVs. Zachary Moxley introduced me to Kajsa Larsson and Celeste Pomerantz, and it felt like we finally found the individuals who encompassed the values of the story.

How many days were you in production?

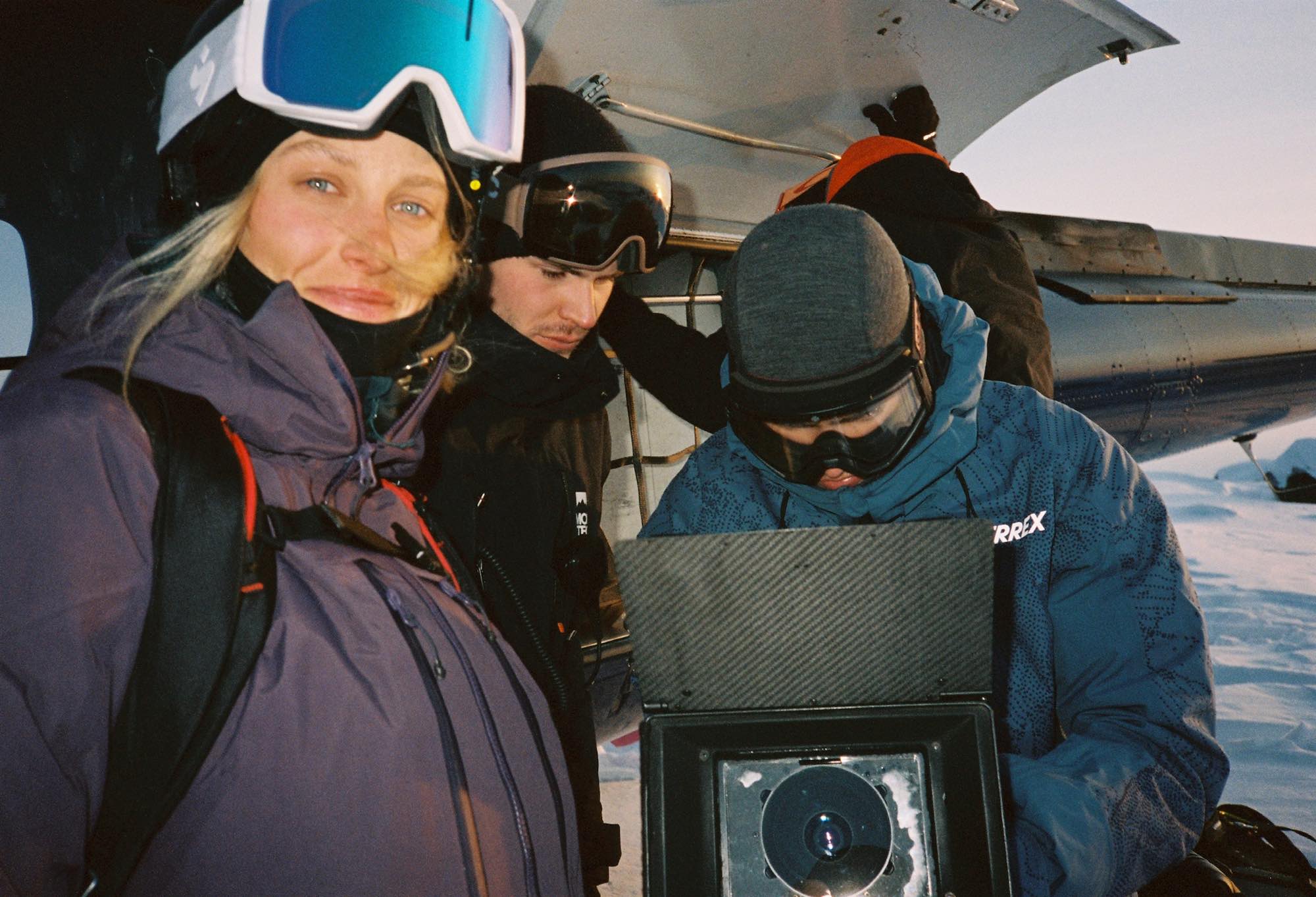

We shot the film across four days with a three-person crew: myself, DOP Christopher Clark, and Aerial Cinematographer Zachary Moxley. As a commercial director, I’m used to big crews with resources. Beautiful things occur when you strip away the luxuries of a traditional production. First, you only ever shoot in the best natural light possible since there is no G&E team. Second, the entire cast and crew become a family working towards the same vision. And third, new ideas you’d never usually have started to transpire.

Shooting most of the movie felt like a stopwatch ticking. Navigating the mountains was a logistical challenge: fuel costs increased each second the blades spun. When you are in the air, every moment counts.

Beautiful things occur when you strip away the luxuries of a traditional production.

Could you break down your process with Christopher Clark in developing the aesthetic of Suspended in Space? The blues you captured look incredible.

DOP Chris Clark and I wanted the film to live in a world of blues, developing a palette of daytime icy blues contrasting royal midnight blues. The Yukon has uncommonly long blue hours in the morning and night, where we could shoot multiple scenes. This meant we’d film exceptionally early and late. Rest would often come in the late afternoon.

And in terms of the skiing footage and aerial photography, what kit did you use to render those shots?

We shot on the RED V-Raptor with Zerø Optik rehoused Olympus OMs; they open up to F2 across a range of 18mm-180mm. DJI gave us an unreleased Inspire 3 for our aerials, which enabled us to meet new altitudes that previous versions could not reach. We often flew at its maximum altitude of 7,000 meters, pushing the limits. The drone was treated as if you were floating through space.

We mounted GoPros onto the talent, not for the shot, but as in-field microphones for natural reactions. Then, we recorded Celeste and Kajsa’s narration as live conversations. We’d talk about our shared feelings and emotions about being in the Yukon and focus on allowing Celeste and Kajsa to share an authentic experience here.

Did blending their conversational narration with the documentary-style footage throw up any challenges during the edit?

Editor Christian Whittemore and I took an unorthodox approach to this film. The narration was the very last part added to the edit. This way, our visual storytelling had to land, and there was no crutch to making a scene work because of a line. Before the cutting process began, Christian and I had a long meeting to discuss sensations and emotions. We don’t touch the edit here, though. The goal is to speak the same language, and then I walk away from the first edit as far as possible. I only have my editor’s first instinct and unbiased eye once.

The narration was the very last part added to the edit. This way, our visual storytelling had to land, and there was no crutch to making a scene work because of a line.

An example of Christian’s great taste is the opening. The script always started by immersing the audience in the helicopter take-off. This way, we earn the audience’s attention and can sit in the land’s charm once we hook them. Christian and I watched Fincher’s Mindhunter intro title sequence for the shot design and Drive, as the chase never shows the exterior car. What I thought would be a relatively quick intro, Christian brilliantly turned into a fleshed-out hook. These are the surprises along the way I love.

Could you talk about the ending and what went into creating those final moments?

The film’s ending is what I consider a ‘snow globe’ moment. We let the final zooming-out drone shot play as long as possible, paired with surrealistic sound design climbing. This ending is supposed to say, “Everything occurred within this moment when time stops, and people can truly live.”

I read that for the score you collaborated with Liam Mour, who recorded everything in Berlin’s Funkhaus Cathedral. What was your relationship like with him throughout the making of Suspended in Space?

I’d like to geek out here and say our Composer Liam Mour has been one of my top-listened artists on Spotify for the last three years. He allowed us to pre-score the entire film with his music. We kept what worked and re-scored areas where the music could be grander. Liam and I felt the music had to stylistically ‘float’ with the story and put the audience into a trance, which was a new creative challenge for both of us. My favorite surprise was Gloria Nussbaum’s vocals in Liam’s brand-new orchestration, which perfectly captured the euphoria of the Yukon.

What are you working on now?

Currently, I am working on campaigns. I love directing in the advertising space, and I am always looking for my next short film or first long-form narrative project.