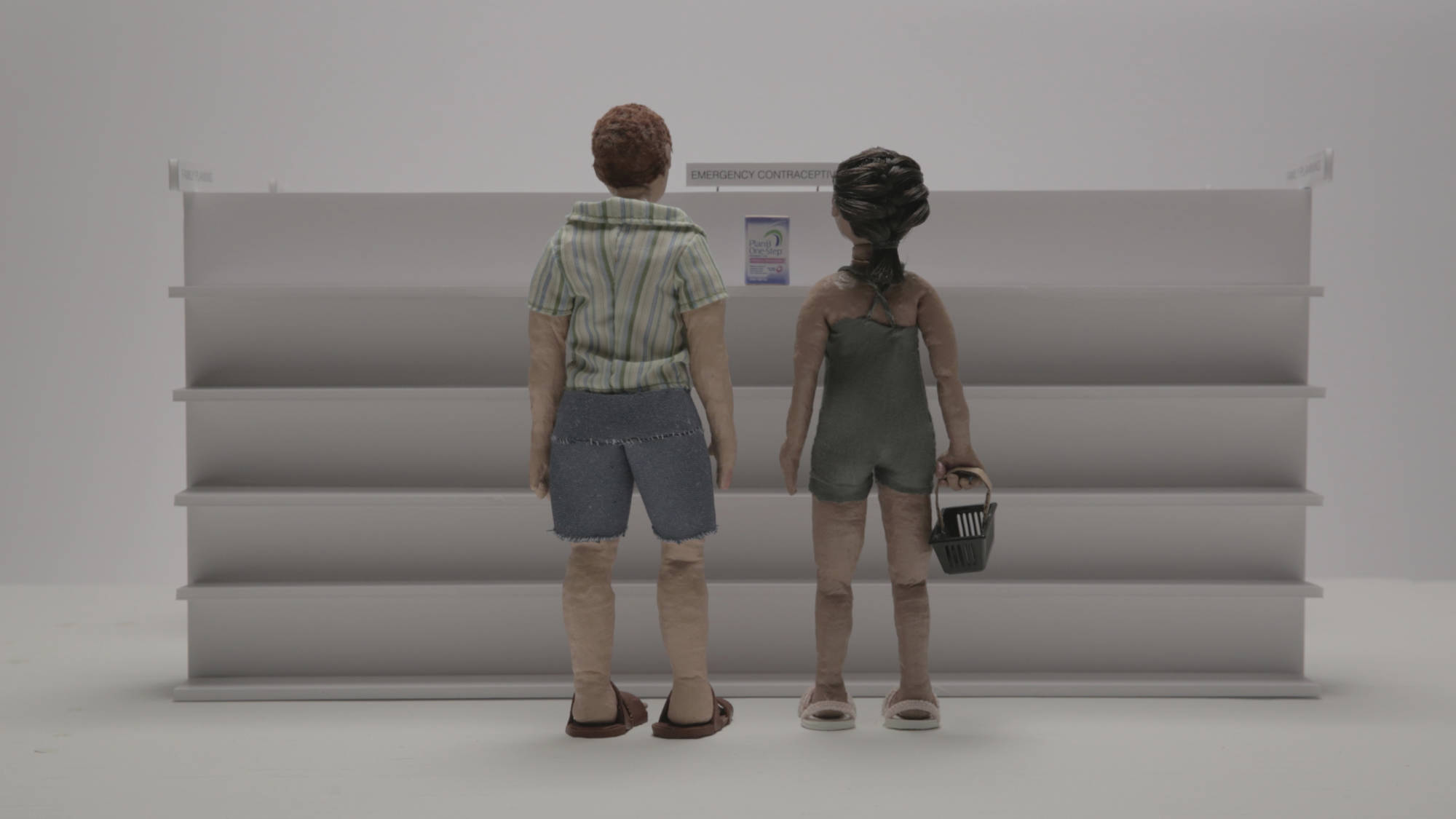

Pairing magical realism with stop-motion animation, Emily Ann Hoffman’s adorable short film Nevada, sees a young couple playfully engage with the future possibilities of a birth control mishap during their romantic weekend away. In our interview, Emily explains how she drew on personal and shared experiences to ground this animated short in a relatable reality, free from the judgemental myths which often surround the topic of birth control.

The roots of Nevada lie in shared and personal experiences of taking emergency contraceptives. Was there a common theme that emerged across these conversations which shaped the approach and perspective you took in the film?

There certainly were similarities across the board! First, there was the constant concern of the negative side effects of Plan B. There are of course the side effects written on the box, that any medication would have, but when read all together they sound much more horrible than what the average person actually experiences. But I had also heard and perpetuated a mythology that you’re only supposed to take Plan B three times, and if you take it more than that it could make you infertile. I’ve now learned — after researching online and speaking with doctors — that this is untrue. Yet these rumors, most likely originated from the shame attached to taking contraceptives, were always part of the conversation. Second, it was impossible not to talk about how our male counterparts handled the situation. Even when their intentions were good, they almost always put their foot in their mouth at some point.

I wanted to highlight how in not talking about these situations, women are isolated in their worry because they feel shame.

These two common threads certainly influenced the story I was aiming to tell with Nevada. I wanted to share all the layers of shame, stress, frustration and worry in these situations, even when your partner is understanding and even when nothing goes ‘wrong’. I wanted to highlight how in not talking about these situations, women are isolated in their worry because they feel shame and because their partner isn’t as well-informed as they could be.

There’s an ease to Zoe and Eli’s playful back and forth conversations which feels utterly natural. How did you achieve that, especially as your actors recorded their dialogue parts separately?

I think it’s truly a testament to my actors! In writing the script, I spent a good amount of time editing the dialogue with my producer and mentor Sean Weiner. We read it aloud and I drew a lot of colloquialisms from real-life conversations. But all that would have been for nothing if Chet Siegel and Jonathan Randell Silver had been unable to bring it to life. They’re both very intelligent and natural comedians, (Chet has a big background in improv), so they’re particularly good with banter. We cast Chet first, who then recommended Jonathan, so I think their pre-existing relationship (even though they didn’t record together!) helped with the on-screen chemistry.

Likewise, it’s refreshing to see the couple presented in all their post-sex glory as opposed to the unrealistic ‘cover under the chin’ bed scenes we’re normally presented with. Why did you feel it important to make puppets with actual genitals for this?

That, to me, was the beauty of working with puppets. It was really important to me to avoid the cliche under-the-covers couple with perfect hair and makeup who are supposedly post-coitus. Naked puppets are silly and disarming, and puppet genitalia is relatively cute. Besides adding to the humor of the situation, I think puppet genitalia is less threatening to audiences. Audiences eventually relax and pay more attention to the character’s humanity than they would if a real penis was on screen. And I don’t have to compromise on the realism of the nudity!

I think puppet genitalia is less threatening to audiences.

Your actors were strapped into a rig which limited their movement during the voice recording sessions. What role did that footage play in the animation processes you used for Nevada?

Besides providing quite a unique challenge for my actors, these rigs kept their heads still while we recorded, so I could then use that footage of their faces to rotoscope my characters’ faces. Rotoscoping is a process of animation in which you trace live-action footage frame-by-frame to create an animation. So after I shot all the stop motion, I then 2D animated the character’s eyes and mouths in photoshop, based off of my actor’s actual expressions. Which is why the character’s faces have that wiggly hand-drawn quality.

Nevada was made during your Creative Culture fellowship with the Jacob Burns Centre. What initially attracted you to the program and how did the fellowship foster Nevada and your filmmaking process as a whole?

I was fortunate enough to stumble across the Jacob Burns fellowship through a well-placed Facebook ad. It was about a year after graduating college and I was feeling a little lost. I knew I wanted to be an independent filmmaker, I was trying to develop projects when I had free time and was teaching myself screenwriting, but it felt very daunting to try to make an animated short isolated in my parent’s basement. I’m forever grateful to have had this fellowship and the support of the Creative Culture program. They provided resources, funding, and most importantly mentorship and moral support. Creative Culture allowed me to participate in a community of artists again so I was able to receive feedback, skill-shares and inspiration on a daily basis.

What projects will we see from you next?

I’m in post-production on a new short film called Bug Bite. It’s a mixed media (live-action and animation) comedy about a millennial and a bed bug who form a unique bond as they simultaneously contend with toxic masculinity. I eventually intend to make a feature film on the same theme.