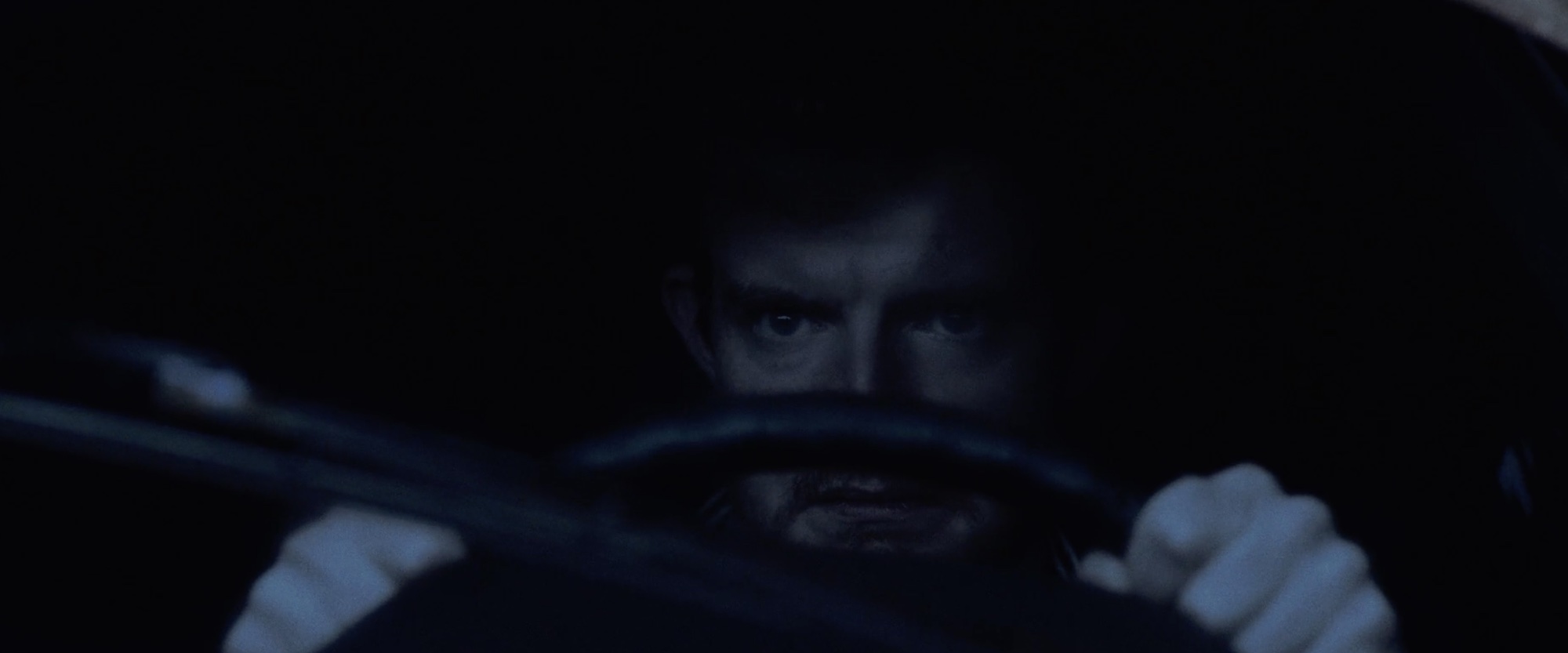

There’s a real confidence in direction in Ciaran Lyons’ brooding tale The Motorist. Everything from the performances to the aesthetic evokes a sense of unease and dread. It sees a lone driver greeted by a strange community whose intentions remain ambiguous, to say the least. Lyons melds elements of folk horror with that of brutal realism, developing a classical mystery that feels like an old tale spun from years past. DN is delighted to premiere the BAFTA Scotland nominated The Motorist on our pages today, and spoke with Lyons about shooting in the remote Scottish highlands, evoking a sense of unease through his cinematography, and the audience reactions that have stayed with him.

What inspired you to create such a strange, folklorish tale?

There are a variety of good reasons for deciding to make a creative piece of work: to inspire, uplift, provoke, challenge, to attempt to instigate social change. Personally, I find that what really excites me is when someone encounters something new and unexpected within themselves (their subconscious, or imagination, or whatever you want to call it) and then tries their best to bring it to life honestly, without distorting it through intellectual rationalisation or by trying excessively to impose their own conscious meaning upon it, but trusting that thing to speak for itself, whatever it has to say. I think that this form of creativity is what gives birth to the archetypes we all know from folktales and fairytales and that the likes of Rumpelstiltskin and Rapunzel enlarge our possibilities of communicating and thinking in ways we don’t fully understand.

I wanted people who watch it to feel like they’re discovering some reinterpretation of an obscure Scottish folk tale.

From that point, where did you go next to develop a functioning plot?

Regardless of how successful I was in my goal, The Motorist was my first real attempt at trying to work in this way, and the something I found within me was the central image of the car as a punitive sensory deprivation cell-cum-tomb. I wanted people who watch it to feel like they’re discovering some reinterpretation of an obscure Scottish folk tale because that’s how writing it felt to me. This may all sound a bit pretentious, but I was fully aware that what I was trying so hard to create was pretty ludicrous, and the whole process felt like a (stressful) form of play.

What attracts you to this particular form of storytelling, one which is more classical and almost fairytale-like?

There are a great many issues facing us in the external world today that demand our attention as storytellers, documentarians, satirists and social critics. And while this is definitely important, I believe we also need to continue listening to the mysterious voices coming from within us that whisper those strange and inexplicable things we would never come up with in full consciousness. I believe those voices have something important to say about who we are, and even if we don’t fully understand them, we ignore them at our own peril.

Could you talk about the practicalities of shooting in such an isolated location?

For some time after the shoot, I would have described it as disastrous, traumatic, and probably the most stressful weekend of my life. I promised myself that I would never do a shoot like that again. But with some distance, I can see that a lot of the elements that made the shoot so difficult were the same things that made the film work.

I knew there was a risk of the film coming across as disorientingly strange so I wanted audiences to always be able to find their way through it via relatable emotions.

For example, our ‘unit base’ involved a line of vehicles parked up on the verge of a single track road by the edge of a wood; a Winnebago for the main cast and a tent in which my mum tried to keep a steady supply of hot food and drinks going. This was a self-funded affair and the credits bear a remarkable resemblance to my wedding guest list! This spot was already pretty remote, and I think arriving at it impressed upon the many friends who had agreed to help out far better than I could have put into words: “This is serious shit. We cannot just slip away to the pub.”

From there it was about a 15 minute walk up a hill to the main location, the tree. Although this was a nightmare for transporting track, the mag-liner, the generator, and probably worst of all the statue, it did have an unexpected benefit – by the time you were up there, it felt like you were in another world. My dad was on hand to drive up and down the hill in his comically non-off-road car, but the actors didn’t want it. They wanted to feel this separation. When the night-extras showed up for the fire scene and saw the welded car in the pitch dark, apparently some of them felt like they had agreed to do something genuinely sinister. So yeah, in summary: it was tough. But although I felt bad about putting people through it, it would have been a different film had it all been a walk in the park.

What did you shoot on and how did you approach evoking the sense of unease through the cinematography?

We shot on an Amira. I have David Liddell to thank for the cinematography, he did a beautiful job of translating the storytelling concepts I was aiming for into a visual reality. The film is essentially a fairytale, and the story is, in many ways, quite ridiculous but I didn’t want it to feel in the least bit light-hearted or whimsical, because it’s also about a man losing his soul to fear. So, for example, we did whatever we could visually to make The Motorist feel trapped and overwhelmed. I don’t really like talking too much about the specifics of things like this, because I think a lot of it becomes quite intuitive once you have clear concepts to guide decision-making. Should we see the reflection of the tree on the window, or should we flag it? Should we shoot this reverse from inside the car, or from in front of the windscreen?

How did you work with your actors to help them understand the overall tone of what you wanted to achieve?

We didn’t actually have a lot of preparation time, because I had spread myself a bit thin across so much other production stuff. My priority was to meet with each of the main cast members individually to discuss how to find a line through all the weirdness that they could connect with in a way that felt real to them. I knew there was a risk of the film coming across as disorientingly strange, so I wanted audiences to always be able to find their way through it via relatable emotions, even if they’re not always able to connect rationally with what’s going on.

The cast all got this but I think the success of my direction had less to do with saying anything particularly useful or insightful to them, and more to do with managing to create this genuinely intense and unusual event, as I’ve already referred to. When you’re up on top of a hill being blasted by wind, seeing a bunch of stressed out guys welding a car shut against the clock; having to actually carry a heavy statue to a bonfire in the pitch dark while a load of folk scream at you, that creates some real stuff to play with. I knew this before, but I relearned it from shooting The Motorist, a good trick for creating intensity on film is to really do some intense stuff.

Now that the film has played numerous festivals, and given that it sits on the line of horror/drama/folklore, have you noticed different reactions from different audiences?

There haven’t been as many opportunities to be in the room with audiences as I would have hoped over the past year, but there have been a few, both horror and non-horror. People’s receptivity to discovering the tone of the film seems to vary, depending upon how they’re primed beforehand. I think when it played amidst a non-horror programme, a more common audience response was that they ‘discovered’ it was a horror, and then felt less receptive to the other stuff in it. Whereas I found the horror audience were already primed for the idea that it was a horror, so were looking to discover what else it was. For example, the non-horror audience didn’t think it was polite to laugh at it, whereas after the horror screening, one guy came up to me and said: “Thank you! That is exactly my sense of humour!” He was referring to things like The League of Gentleman, The Wickerman and Midsommer. So I learned that different people bring different expectations and preconceptions – particularly with something that tries to straddle so many lines.

And finally, what’s next in store for you?

I’m currently directing a sci-fi ballet piece, which is exciting. I’ve written quite a few projects that I’m trying to figure out how to find the cash to make, but the inertia of lockdown is making me itch to just make them, on any scale! And this short is starting its festival run: The Mad Shagger. That may be another (even more extreme) example of preconceptions battling with content… although it has a trashy title and aesthetic, I was really trying to tackle a difficult subject sensitively and thoughtfully. I think there’s something perverse in me in a filmmaker that wants to risk being misunderstood.