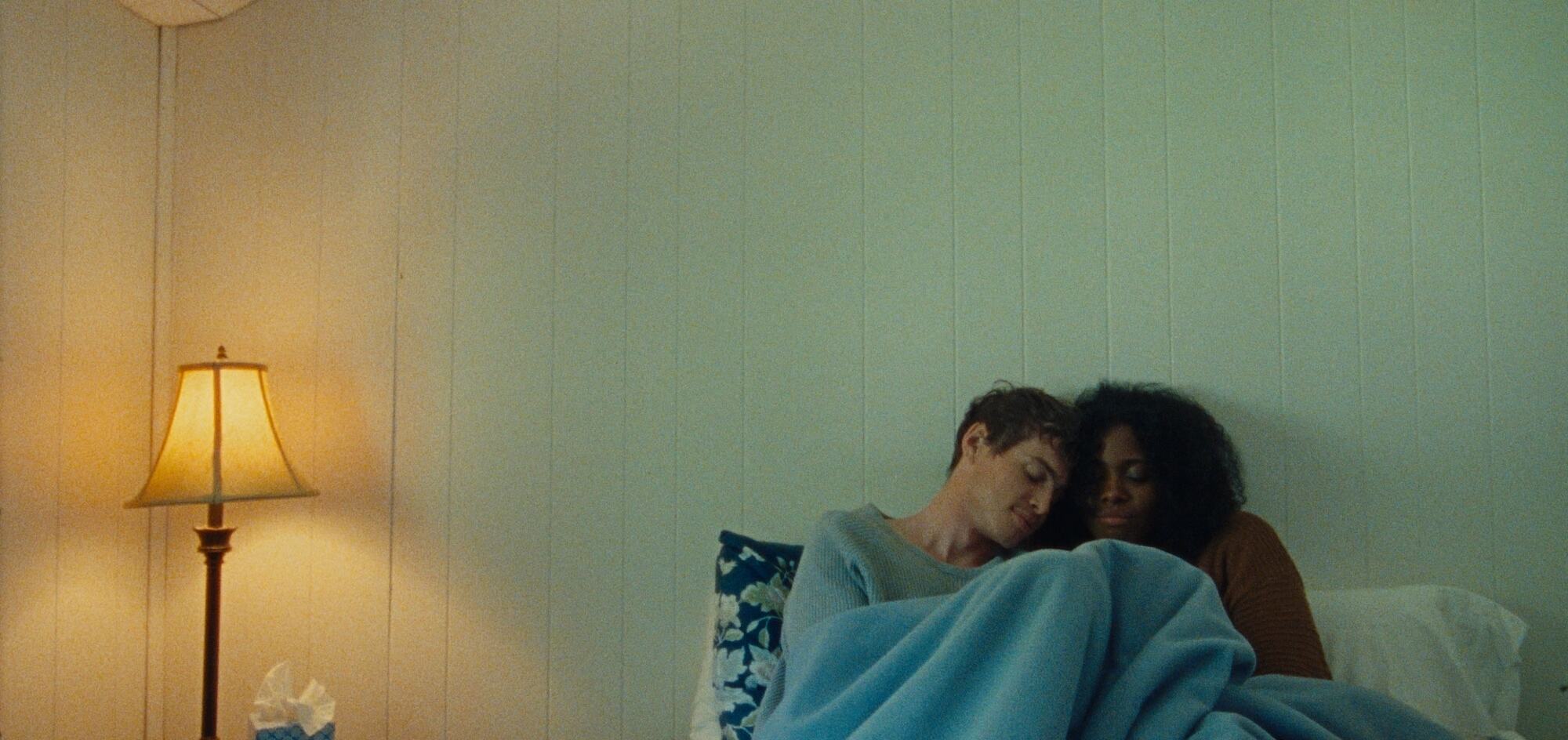

Gabriel Connelly’s latest short film Swimming for Shore is an adaptation of Chrissy Kolaya’s short story of the same name, about a young woman facing the lasting traumatic effects of a tragic and random accident. What’s clever about how Connelly tells adapts Koala’s story is how he approaches the film as a fragmented representation of memory. This isn’t a chronological account of what happened, instead it’s a collection of glimpses into the accident itself and the relationship involved. Connelly, whose camera skills we admired in Ewurakua Dawson-Amoah’s We Are and Alex Fischman Cárdenas’ Neptune’s Dream, captures this account on tactile 16mm too, a perfect format for replicating the visual essence of memory. DN caught up with Connelly for a chat in which we discuss his decision to utilise 16mm for this particular story, how the project evolved across variations of visual styles and tones, and his journey transitioning from documentary filmmaking over to narrative.

How did you discover the short story of Swimming for Shore and what intrigued you about adapting it?

I came across Chrissy Kolaya’s piece Swimming for Shore in a collection of short stories a couple years ago and had been toying with the idea of doing a film adaptation of it for a while. The idea went through a ton of variations in terms of style and tone before it became the eventual end product. I had been doing a lot of work in the short documentary world and was itching to take some of the things I’d learned from those projects and apply them to something totally fictional and explore more surreal visuals.

Had you ever gone through the process of adaptation before? How did you find it?

I have not! Chrissy Koyala wrote the original piece and was very supportive of the whole process. It was a really cool experience to basically have an expert on the original text that I could talk to and get feedback from. I also had never really gotten to talk to the author of a piece of writing I really liked before, which was really interesting. You know, when you’re in English class, you get to just have unlimited interpretations of a short story, but with this one, I had the author telling me which of my interpretations actually lined up with her original intentions. That being said, she was really into letting me have my own take on the story and not feel restricted to her original text.

You mentioned that the idea for Swimming for Shore evolved through a variation of tones and styles, what did some of those look like?

Yeah! I experimented with a lot of different versions of this film during the editing process. I think I did something like 30 different cuts. I had gotten so used to working on documentaries, I found myself really challenged by the level of freedom a fictional piece gives you. The initial versions of the film were a lot more traditionally narrative. I really wanted to lean into this ambiguity about whether our lead protagonist is telling the full truth in the narration when she tells us that she “couldn’t have saved him.” In the early cuts, that drowning scene was a lot longer and had a moment where Joshuah waves at Imani for help and she ignores him. It took me a lot of cuts and notes from friends to finally admit to myself that the scene wasn’t working.

I really wanted to lean into this ambiguity about whether our lead protagonist is telling the full truth.

I really learned a lot about directing and writing through the whole process. Like, you can write in a script that a character “waves for help while slipping below the water,” and you accept that as a reasonable thing, but then when you get on set, you suddenly have to figure out how you show that someone is drowning. And on top of that, how do you show that someone is drowning, but still capable of waving for help? And then how do you do all of that while shooting through a fish tank in a lake, and not getting any of the equipment wet? After cutting down that scene, I took the film in a much more lyrical direction which I think was the right call. I was also massively aided by the stunning score that my friend Antonio Romero created for the film. That score really tied the whole thing together.

From a visual standpoint, it looks gorgeous. Where did you shoot and what formats did you shoot on?

I ended up shooting the film with a bunch of my closest friends up at a lake in Vermont over one weekend at the start of September. We shot it on an SR3 16mm camera with a 6mm and a 9mm lens.

Why did you feel 16mm was the right format for this project?

Well, I knew that the project had to be shot on film very early on. I really wanted to experiment with these dreamy moments where I undercranked the footage and alternated frame rates within a single shot. These analog cameras are so fun to shoot on because you can really play them like instruments and find these little tricks with how the camera works in order to find new looks. Sometimes that meant stuttering the roll button, flipping the undercrank switch back and forth during a take, or intentionally leaving the eyepiece open for a shot. You can’t really do that on digital cameras. I also really love the way that 16mm adds this warm halation to highlights and knew that it would make the water scenes look really amazing.

What specifically have you learned making documentaries that you carried over into this short?

The last couple pieces I’d worked on were both short docs with a very lyrical editing style, where I basically attempted to treat interview VO like a poem. I wanted to see if it was possible to apply that style to a piece of fictional VO. I definitely learned some of the limitations of this approach when it comes to narrative. Some of my favorite moments in those docs were when the subject would sort of ramble off about a subject and accidentally say something really amazing. It’s a lot harder to find those really off the cuff pieces of VO when you’re working off a script. Our actress, Imani Love, did a really lovely job with the VO though and added such a lovely quality to it and read a few of the lines in ways that I never would have expected.

How long did it take you to bring everything together in post?

The film took a lot longer to edit than I expected. I generally consider myself a pretty fast editor but this one took me close to six months to put together in a way that I felt happy with.

These analog cameras are so fun to shoot on because you can really play them like instruments and find these little tricks with how the camera works in order to find new looks.

What can we expect from you in the future?

I’ve been continuing to DP and work with some really amazing directors. Directing wise, I’ve got a fashion commercial I directed and shot that I’m hoping to finish in the next month and I’m in pre-production on a documentary about rodeos in Oregon that I’m really excited for.