Drawing inspiration from controversial artist Tracey Emin, brothers James and Harrison Newman’s sophomore short Do Not Touch, starring British Comedian Seann Walsh, thrusts one man’s infidelity into the critical glare of an art exhibition, forcing him into the desperate role of art saboteur in the hopes of destroying the evidence before his girlfriend discovers his betrayal. It’s a delightfully uncomfortable comedy which simultaneously shines a light on the very public nature of breakups and the divergent views on what can be considered art. We sat down with the Newman Brothers to learn about the creation of Do Not Touch and spoke to them about the unseen advantages to knowing who you are working with as intimately as family do, how they created a world in which the comedy is believable and not just farcical, and the nuanced ways in which they remind the audience of the emotional stakes at play.

What are the roots of this uncomfortably funny most public exposing of adultery?

James Newman: Do Not Touch was always an episode of a sitcom for me. It’s something that I kept thinking it would be a shame that if we never made the sitcom; we’d never make that episode. But I realised in isolation that it’d work as a short film. The idea came from Tracey Emin’s Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 (1995). I originally thought the artwork was displaying used condoms in a gallery of everyone she’d ever slept with a photo – but I was wrong. It turned out to be a tent with the names stitched inside. But that false memory turned out to be a great pastiché and we used that in the final film. At the time we were surprisingly the finalists in the Kino London Short Film Festival with our short film comedy debut, a scandi-noir farting crime caper, Viskar I Vinden. We were up for the £1000 film fund and we were very, very surprised to win. Working with Kino London and Dustin Murphy, who runs Kino London, was amazing. Dustin was acting executive producer and he was incredibly helpful, guiding the production and improving the production, whilst letting us have creative freedom.

Harrison Newman: When James first mentioned Do Not Touch to me, He already had the concept and characters mapped out. We briefly discussed format and genre and developed from there creating some of my favourite moments in the film, such as the projection and montage sequence at the end. At which point James does his thing and writes iteration after iteration of the script and within weeks we were at script lock.

James, what is your particular approach to script writing from the initial concept?

JN: For Do Not Touch, I got the pitch, and saw how people reacted to the concept. I was pitching to directors at festivals when they’d ask us what we were working on next. You’ve got to have a concept that connects and excites you. I then map out a basic structure of story beats using the story circle technique which is a reduced version of the hero’s story. From there I find that the situation and story dictate the beat sheet of what needs to happen, and I make sure all the beats have a ‘therefore’ and ‘but’ between them for cause and effect. I then do a first draft, which we call a ‘vomit draft’ as it’s written so quickly and is just the bare bones. It then goes through loads and loads of rewrites.

In fleshing out you’re also cutting down and only leaving what you absolutely needed.

I have a sort of ‘brain trust’ who read and feedback on the script. Is it playing like I want it to? Does this dialogue work? Is it even good? If not I’ll tweak and change things. In fleshing out you’re also cutting down and only leaving what you absolutely needed. I’m looking for economical ways of giving information, for example the plant is quite important. In the film the main character doesn’t think it needs looking after as it’s a cactus, but it’s not a cactus and it does need looking after. And in the last shot of the film the plant’s dead… we tried to use this as a metaphor for their relationship and how he takes their relationship for granted. Devices like that add something to the end piece even if it’s not obvious.

How do you find the dynamic of working together with James doing the majority of the writing and you both directing and producing? Are there any clashes or perhaps advantages to this setup?

HN: So James and I operate as a directing duo, I think if we weren’t brothers we would clash however I find that our years of clashing have helped us with communicating on projects. As James writes, I think I pair very well to co-direct with him, as I know him better than anyone. I can understand and comprehend his writing as I have such a close connection and such a large shared history I often know the moments in his own life that he refers to or I can collate moments of our shared experience that he draws from and therefore can challenge his creativity and thought process without it offending our egos. As his brother I can see parts of the script that are incredible and help him develop parts that he may have neglected as he focuses on the main narrative. I think that balance helps us to flesh out the worlds we create and hopefully makes the audience feel perhaps more attached or invested. I believe that it also places the projects in a different light for me, as I not only want to do it for myself, but I also want it to do justice to my brother’s incredible talent.

JN: The advantage to it is that Harrison comes in with fresh eyes and sees some differences in the text than I do. Because when you’re seeing it from a different perspective when you hand it to a director, it’s good to work like that as it works like two sides of a brain. Something’s a creative decision but then is questioned; does it fit in this world? So I only think it’s a good thing working on these parts as we both have different skill sets which don’t really overlap. Harrison has a great production brain and has really great skills in world-building and visualising and bringing that to fruition. I think the key is we both know how and when to compromise.

With such a fine, but incredibly well tread line, from comedy and drama and the absurd yet relatable, how did you work with your crew and set the right tone within the shoot?

JN: The rule we have is “play it for truth”, rely on the situation to bring out the comedy and everyone lives in a drama world. So we’re looking for people who have funny sensibilities but can do drama. The comedy really relies on believing in the world; if they’re winking to the camera you immediately don’t believe the stakes or the characters. If you don’t believe what’s going on it takes away from the comedy. We put a lot of trust into our performers and let them try things and make suggestions. We were incredibly lucky when it came to casting. On our level, which is like people are sort of willing to work with us now if they’ve seen the first film.

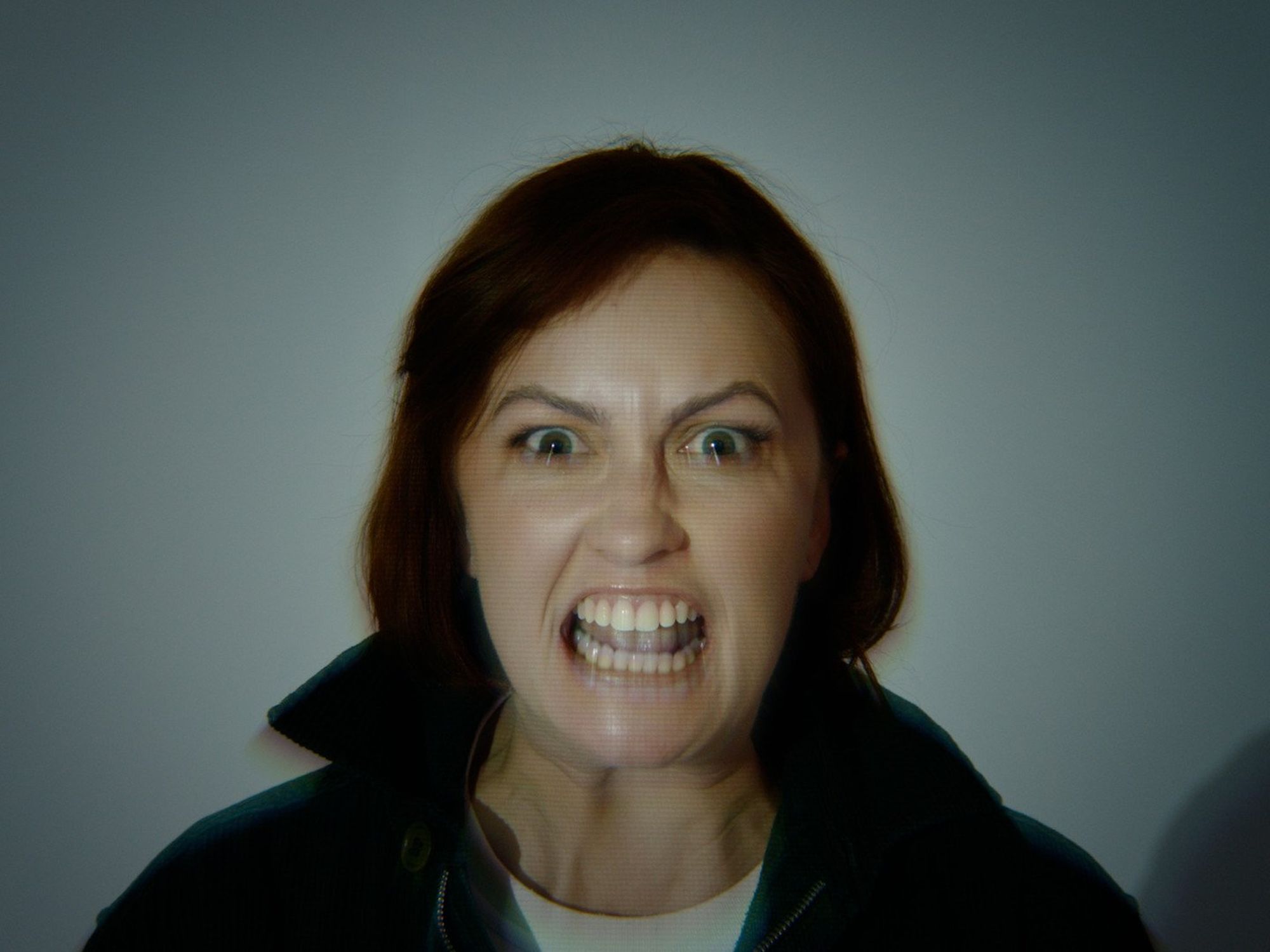

Unbelievably we met our lead Seann Walsh at a film festival, we saw his short film Clown at the festival so we knew he had the drama chops to fit our film. Charlotte is also a serious actress and writer who does comedy and drama, so that was a no-brainer. Sofia, who played the artist, we’d worked with before on our first short so was another no-brainer. Blair, Julia and Ingrid were all cast for the same reason as they’re all drama backgrounds but had the sensibilities to do funny so we were so lucky to get that cast. So we look for drama actors really who play these stupid situations straight – it feels like a bit of a cheat code.

We decided by shooting in 4:3 we would create awkwardness in the framing, making him shut off, tunnel focused on the artwork of his demise.

HN: We knew we had to set a tone for the film to progress and determine how we would direct our departments for this to work, we followed a similar tone to our last film Viskar I Viden, in that we used serious camera techniques while contrasting the ridiculousness of the situations which is in turn carried by powerful performances which Sofia Engstrand who has been in both, and the rest of our cast pulled off incredibly. The dedication to stupidity the whole crew had was fantastic.

After this was established, we knew we had to aim for a fairly unique look that sits on the border of serious and comedic, so we went for a veneer of drama while the movement framing and narrative undermine it each second. We decided by shooting in 4:3 we would create awkwardness in the framing, making him shut off, tunnel focused on the artwork of his demise. Whilst framing others off-centre in frame to indicate his current mental state. The Cooke 25-250mm we used to give us the base of the look, its convex nature draws the face into the lens and in doing so brings the audience closer to the subject, with our anti-hero protagonist we need all the help we can get.

I wanted to remind the audience someone is being hurt in this narrative.

I’m no cinematographer, I picked up information by working as a gaffer for the last two years and shooting our last film, so I picked the kit, but it was the wonderful Sam Loane who operated on the day, we had several talks prior to the shoot to explain the look we needed and how we’d like to capture it to be most economical of our time and others by shooting out the scene in our masters typically keeping it on Steadi to keep the film’s pace moving. It rarely stops only in one of the shots in the penultimate sequence, a single on Charlotte which I operated. I wanted in that moment of the comedy to bring back a moment of seriousness, a handheld shot to get my breath into the movement. I wanted to remind the audience someone is being hurt in this narrative which possibly the montage directly after undermines slightly.

Harrison I love your decision to shoot in 4:3 and the details you were able to capture with the camera and angles. Did you do a lot of camera blocking for the shoot?

In terms of blocking we didn’t do much, luckily the flat we used was James’ so I was quite familiar with the space. This made it a lot easier when it came to visualising the shots. As I tend to read the script and visualise the frames as I go, each read and conversation manipulates the images that I draw on. The more I delve into the characters and core of the story the easier it becomes. At the beginning of the project I was trying to get away from Viskar’s style but found in the final project I was probably too close to it for my own liking. Once I had the frames in my head I used floor plans and knowledge brought from lighting on many short films to manipulate the space and equipment to achieve as close to the desired frames as possible.

We tend to air on the side of caution. We shoot out our masters making sure we have the scene in the can and then we move on to our shots that would help us further the film and lastly some safeties for the edit. This way we know if we run out of time on the day for whatever reason the scene is complete and we may gain some extra production value in the meantime.

Did you work on the edit together and what do you think you learnt from your first film which both of you brought into the mix this time?

HN: I was gaffing a feature while we were in post production. James cut the film and would send me the draft on Frame.io so that I could send time coded feedback. I think what we brought from Viskar was possibly a lack of coverage. For Viskar we shot eight pages in one day, we had more time with this film so we made use of it and made sure to have more coverage for the edit.

You want someone who’s going to take creative risks to collaborate with.

JN: To add to Harrison’s answer the biggest difference for me was the sound. We’ve worked with Jake Davies before on Viskar and love working with him. But the biggest lesson was finding an awesome sound designer. We were again lucky enough to find such a great sound designer called Liam Lucas who took his own spin on the film. I think we gave him two notes and he just got it and has such a great eye for detail. You want someone who’s going to take creative risks to collaborate with.

What has the reception been like in your festival run and what type of conversations had the film sparked?

JN: The feedback for the project has been fantastic! It’s always a bit nerve-wracking to show your work to an audience, but the response has been overwhelmingly positive. People are really enjoying it, and I couldn’t be happier. One thing that’s been really great to hear is how much people are loving Seann’s performance. He’s just killing it in this role and it’s been so cool to see people talking about it. All in all, it’s been a really exciting experience and I’m so grateful for the positive reception it’s received. It’s great to know that it’s resonating with people.

What’s next for the Newman Brothers, I see there’s a project called When One Door Closes that you’re involved with?

JN: Yes, we have been busy helping our friends, the Toms, with their debut short film When One Door Closes. We are currently in the development stage of our debut feature film with a production company. We’re excited about this project and can’t wait to share it with everyone. On top of that, we’re also working on a web series with Seann and the crew. It’s a great opportunity to continue working with such a talented group of people and we’re looking forward to what we can create together. Overall, we’re over the moon that we’re busy!