The Red Suitcase (La Valise Rouge) by Iranian Director Cyrus Neshvad is a crucial addition to this year’s Oscar nominated live action shorts. A clear allegory of the relationship between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the country’s female populace, Neshvad’s film dials back the scale to bring us face to face with such injustice on an individual level, as seen through the eyes of an incredibly strong young woman fighting with her all for her freedom. His largely dialogue-free film ratchets up the tension from its opening scene as our teenage protagonist uncertainly navigates an encounter with customs agents through the fog of a language barrier. The situation only deteriorates from there as we slowly become aware of exactly why she is in this airport all on her own, unable to speak to anyone or ask for the help she clearly needs. Through carefully placed visual markers and detailed production design, the film plays out as a tense game of cat and mouse which keeps you holding your breath right up until the final carefully drawn out scene. A film very much in keeping with the values of International Women’s Day, we were able to take some time with Neshvad (which you can watch in full at the end of this article) to speak about working with actor Nawelle Ewad on her powerful performance, why he chose the base the short in an airport and the imperative he felt to create this story as a response to Iran’s crackdown on its women’s demands for freedom.

[A heads up the following interview contains spoilers.]

Why did you choose to tell this story to talk about the lack of women’s rights in Iran today?

I have a family in Iran who my parents are still connected to. We had a discussion two years ago when my mother told me that she’d heard from her friends that women are disappearing, either for saying something or not correctly wearing their headscarves and this terrified me as nobody was talking about it. So I said, somebody has to do something which led me to the short movie.

The threat is always there but I let the audience breathe a bit and then suddenly get very close again.

How did the story come together to form what we see in The Red Suitcase?

I decided to have my first leading character as a Persian-Iranian girl with a headscarf. Then, I was searching for a situation where I could put her which had to be in Luxembourg as I cannot go to Iran as I’d have problems. I connected very quickly to the idea of an airport. Usually airports are places where you go on holidays and where you have a good time. I thought it would be perfect to show a place which is normally associated with fun but is somehow her exterior and internal prison.

The airport is quiet and the game of cat and mouse very quickly becomes terrifying, how did you build that feeling of mounting tension?

The threat lies in them both being there but him not knowing where she is. But suddenly he knows that she has a red suitcase, so he’s getting closer. Then she finds a way to hide it and we think it might work out but suddenly he finds her the paper that she had in the rubbish and he knows that she must be really close. The threat is always there but I let the audience breathe a bit, and then suddenly get very close again. For example, the bus is leaving and we are happy. Then it stops, what’s happening? No, it’s not him. Suddenly, in that moment, we trust things might work out but he’s already there, he’s entering the bus and the door is closed. It gets more and more tense like this, a bit of breathing room then more tension.

On the surface, our male character doesn’t seem too dangerous but, as with the game of cat and mouse, the threat of his presence accelerates very quickly.

The threat level lies in the fact everything about this man is to do with money. I wanted him to be very well dressed. It was important for me that he has a very expensive watch representing his power. Then slowly we understand his thought process, I bought this girl so she belongs to me. It makes him threatening because he’s powerful, because he’s rich. At the beginning, he’s nice, then you see when he’s on the phone to her father, he’s getting more and more intense. At that point, we see that there is no friendship. Then, when he enters the bus everyone falls silent, we are scared of him. I wanted to put a bit of humanity in him because he’s a human even if he’s not nice.

I thought it would be perfect to show a place which is normally associated with fun but is somehow her exterior and internal prison.

I desperately wanted someone to help her throughout the film but no one does, what were you speaking to there?

The first step has to come from the girl. She has to say something for anybody to help. But, she was raised in a way that she cannot believe that’s a possibility. She is dominated by powerful men, her father and a man who thinks she belongs to him. It’s very difficult to be raised like this and to think that help can come. If she would have been raised in Europe she would have gone to the police but it’s not the same education. Her education is of obedience. This is the situation for women in Iran right now – you need to obey, you need to wear your hijab.

Speaking of the hijab, the scene where we watch her removing it in the bathroom is so powerful, she has this real vulnerability but also incredible strength. How did you develop that performance?

Nawelle decided that she needed those tears. I told her that I didn’t want anything from her, I just wanted her to be real in this situation. I didn’t want her to push and to give me tears for my shot. No, I wanted it to be real. I wanted her to process her feelings, and I just wanted her to know that when she’s taking off the hijab, she’s going against her family, against her education, against everything that weighs on her shoulders. I wanted her to take this baby into her hands and see how she will feel with all this.

I was also surprised by her performance, she gave me something which I was not supposed to get. The only thing I said that was important for me, was when she was removing the scarf, not to look at the mirror but at the lens of the camera. This was very important for me because I wanted her to pass a message out to women in Iran, if you don’t want to wear the hijab, the headscarf, you can take it off like me. Join me in doing this.

What significance does the colour red have in the film for you? You have the red suitcase, you’ve got the red lighting when she’s hiding in the bus and more visual references, what was the meaning behind these?

Red was not significant in the beginning. I wanted a suitcase which, for me, was her heart. So I said to my actress, it’s your heart and I want you to keep it so close to your heart that it can almost take the place of your heart. And then our hearts are red so let’s use red. The main intention was that it’s her heart and that’s why everything in the luggage is so special. I then picked out the items one by one to represent what is in her heart. The flowers were also red which represented him smashing her heart on the floor. Then in the bus I wanted the curtain to be red to have a reminder.

I wanted her to pass a message out to women in Iran, if you don’t want to wear the hijab, the headscarf you can take it off, like me. Join me in doing this.

The most important representation came when we are in the trunk of the bus. When the guy is taking away her luggage he is ripping her heart out and then the trunk is closed. I was really insistent that we had the red colour there. At that point, the red was the memory of her still having her luggage but the luggage is gone. How do you visually represent that she is still thinking about it? I said, “You cannot show this with a voiceover. Let’s put a red light and this will be the main action in the whole trunk.” She is in the middle of the suitcases which are not red any more, but the red light is there.

One thing I did notice is that there’s a distinct lack of dialogue in the film.

First of all, I think things in life rarely happen in dialogue. You can tell someone “I love you” but your actions don’t say that. Or you say, “I love you” because you’re scared to say “I don’t love you”. Furthermore, even if she could talk, nobody would understand her so the words she has aren’t useful. It was clear to me that dialogue would not be enough to express her.

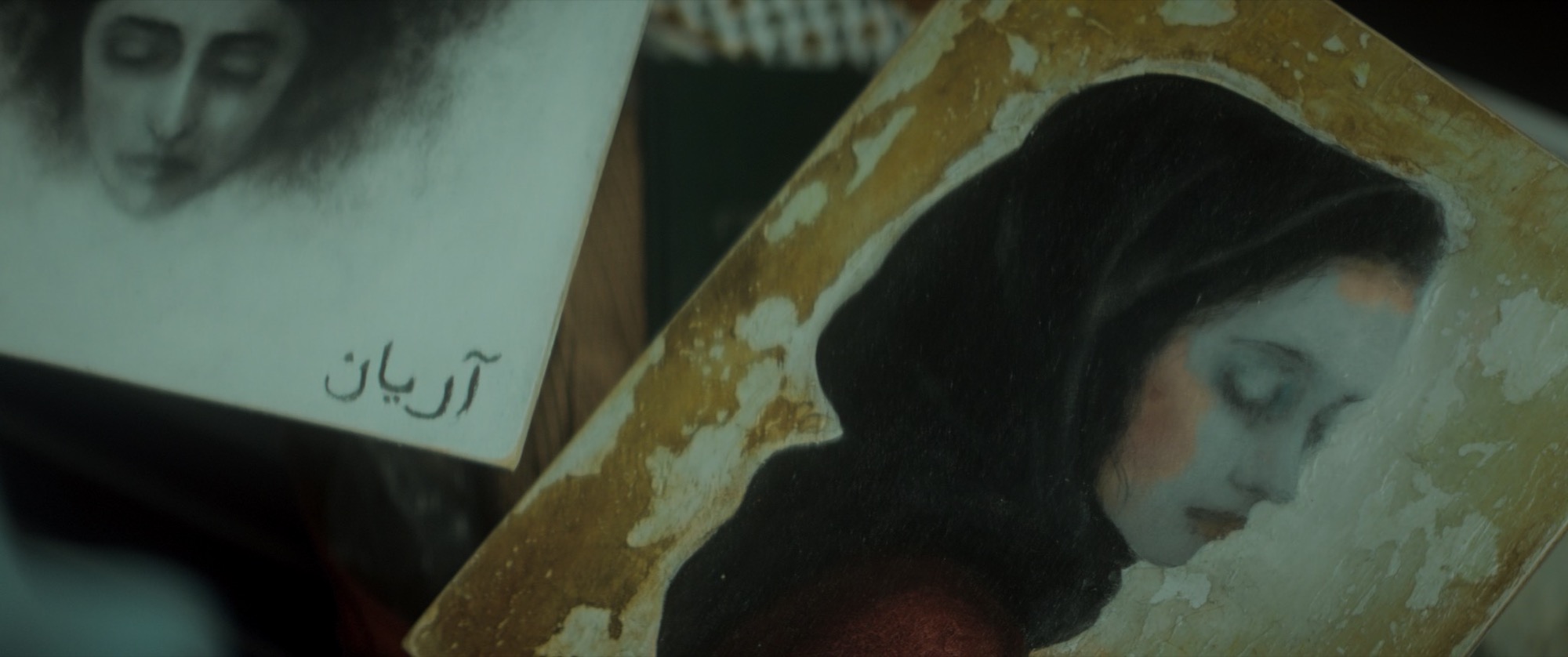

In building her character and the contents of her heart, you have all those significant items in her suitcase, why specifically did you choose art?

Because art is prohibited in Iran, you can only make the art they tell you to. In the painting you can see the woman’s hair and I don’t think this kind of painting would be acceptable so I wanted to have something like this in the luggage. Also in the moment she’s taking off her headscarf, it was important to me that it should be this visually black material falling on art, the black is eating the art which isn’t accepted by the government. For me, it was visually interesting to show it like this.

How important has The Red Suitcase’s Oscar nomination been for you?

This Oscar nomination is important for me as we have more visibility. This makes me so happy, especially today as at the moment we are talking, a young generation of Iranian men and women are in the streets, hand in hand, being shot and killed, but they are fighting for their freedom. So if I can somehow, no matter how little, contribute to this, it makes me really proud. That’s the nomination for me, that I can somehow be on their side from here.

And what are you working on next?

I am working on a feature movie which is the story of a six year old boy who is fleeing Iran with his mother. They finally land in Luxembourg and are living in a camp where the boy befriends an old Russian woman who is taking shelter. This is the story where two people become friends who don’t even speak the same language. They don’t have the same culture, they cannot even understand each other but they become friends.