Although I’ve been a fan of stop-motion for years, the craft and artistry that goes into this particular animation technique continue to be a source of amazement for me. The tactile nature of the puppets, sets and props, combined with the attention and time that goes into it, means that when a director gets it right, they can be some of the most exciting works in the short film arena. Case in point: Joseph Wallace’s new film Salvation Has No Name, which not only made it to the elite cohort of short films on this year’s BAFTA longlist but also did the same for the 2022 BIFAs. A modern epic sporting a timeless aesthetic, Wallace returns to DN with his most ambitious work yet, a film that was years in the making, but well worth the wait.

Welcome back to Directors Notes Joseph, let’s start with things off nice and simple, can you introduce your film Salvation Has No Name to the DN audience?

Salvation Has No Name is my latest short film; it’s a cinematic, seventeen-minute stop-motion folktale which explores the refugee crisis and xenophobia. The film is a true labour of love, a passion project that has been, in itself, a mythological odyssey to bring to life… but more on that later!

We’ve been covering your work for over 10 years now and I was wondering how long this film has been in the works, when did the idea originate and what was the inspiration?

Wow, where has the time gone? I started writing and developing ideas for the film back in 2014, so about eight years ago. During that time I’ve made various music videos, adverts and other projects but Salvation has been a constant creative presence in my life for that period; gestating and evolving alongside the other works. Since 2019 it’s been my main focus other than pausing to make animated sequences for Edgar Wright’s doc feature The Sparks Brothers.

Getting Salvation made was unintentionally lengthy; it took a long time to raise the money for the film, mainly due to the lack of funding for independent animated shorts in the UK, and then we were hit by the pandemic and had to close down the puppet shoot for almost a year! One benefit of the long financing period was that there was a lot of development time which helped to craft a rich story. I began with a few different, and rather disparate, strands in my head:

Thematically, it was a time when, on a global scale, lots of things were shifting politically. This was pre-Trump and pre-Brexit but the cogs of nationalism, xenophobia, border enforcement and a general lack of compassion for those in need were very much in motion. What became known as the Mediterranean ‘refugee crisis’ unfolded in 2014-2015 and I wanted to make a piece of work that dealt with my fear of this regressive world, a fear of right-wing ideologies, a fear that as a race, we had become unkind people. What had happened to helping those in need, why were the international histories of migrating nations suddenly forgotten, when had we become so heartless and closed?

I was interested in exploring the archetype of a Priest as an anti-hero.

Alongside these questions (and they were very much questions that drove the initial writing of the script, rather than answers) was a visual palette of Sub-Saharan African art, Oceanic sculpture and a vague notion of a circus, which conjured up the idea of playing with the conceit of storytelling itself. This sat alongside Mediterranean films of the Neo Realists, early European cinema, South African photography and specifically a great deal of this imagery was black and white. I’d made a micro-short called La Forêt Sauvage in 2014 which was inspired by Paul Klee’s hand puppets and the Italian tradition of Pulcinella and Salvation was almost an extension of that early visual exploration.

Finally, I had made a collaged painting years ago back in maybe 2011 or 2012 of a character stood on the edge of a cliff, holding a baby over the precipice (see below). I don’t know where the image came from, it just emerged from the creative process and for years after I had it above my desk in my studio and would wonder what would drive a character to that point, to commit that action. At some point that character turned into a Priest. I was interested in exploring the archetype of a Priest as an anti-hero and so the film came from those three strands; theme, form and character.

Although a piece of fiction, the story of Salvation Has No Name touches on some very grounded and relatable themes, like xenophobia and the refugee crisis, as you just mentioned. Although we’ve seen these subjects covered before, your film adds a fresh take on them, which feels vital to its success. How important was it to you that you were presenting a new perspective and what do you hope an audience takes from a viewing of the film?

It was quite a complex process writing the film. I knew I wanted to make a piece that dealt with these big themes and addressed what was going on in the world. As artists, we’re in a position of privilege and I increasingly felt that I wanted to use that voice and that platform to tell stories that mattered and that really tried to illuminate injustice and ignite discussion. However, whilst I did copious amounts of research, spoke to refugees and talked to experts on the subject matter, being a refugee is obviously not a lived experience for me, and somehow through my personal grappling of themes and perspectives, the film almost became about storytelling itself. The framework of using a Shakespearian ‘story-within-a-story’ became a device to explore narrative ownership, characters’ agency and how our perception can be skewed by unreliable narrators.

Salvation is quite a dark and layered film but it’s also hopeful.

I wanted to make something that drew on my background as a theatre director, working with actors, playing with the non-literal metaphor and fluidity of space that theatrical storytelling allows. And so telling the story through this window gave us a framework and made the whole thing feel like a folktale, like an allegory. We’re not telling the story of a refugee woman, we’re telling a story about a refugee woman who’s having her story told for her and addressing all of the problems and moral challenges which that throws up. This ensemble of clowns are righteous in their performance but their tale is utterly misguided and hateful and the audience has to learn to distrust the narrator as the film plays out. Salvation is quite a dark and layered film but it’s also hopeful. In a time when the world can look bleak and unforgiving I hope it can hold up a mirror to enable reflection on the last few years and give a sense of compassionate momentum going forwards.

Talking of those clowns, I love the character design in your film as each puppet has such a distinct, individual personality. Can you give us some insight into how you went about creating them?

The design of the ensemble of characters also evolved over a long period. There were various inspirations for the puppets, mainly sculptural, from Sub-Saharan African art, Oceanic sculpture to indigenous masks as well as religious oil paintings and also stage makeup from works by French choreographer Maguy Marin. The Piccolo Clown was an homage to a character from Tod Browning’s 1932 film Freaks. The energy of the Priest was pulled from 17th-century Spanish religious artworks and a great deal from the paintings of Francesco Goya (whose work is often massively theatrical).

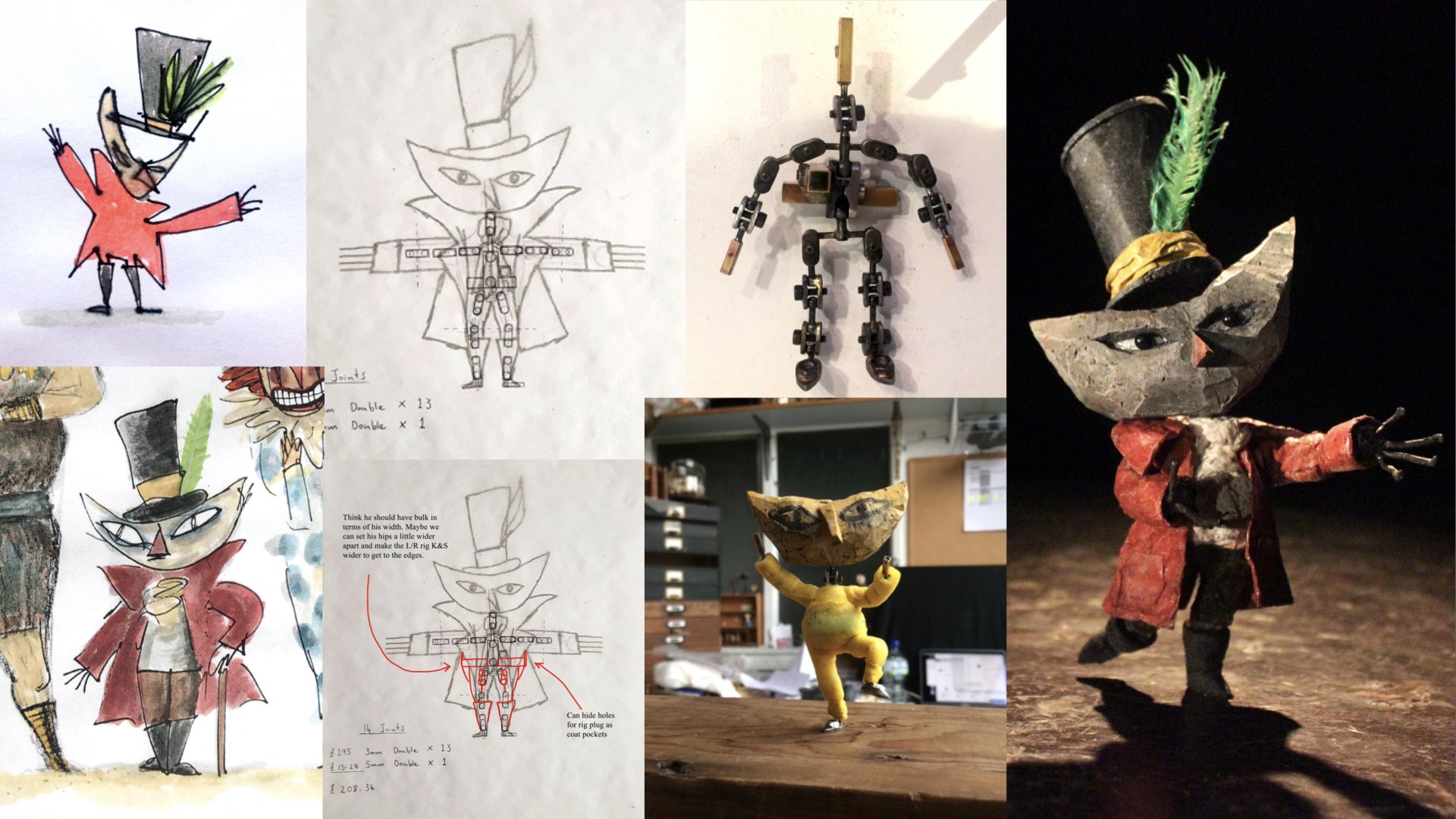

Some of the Salvation characters look very similar to their original sketches (see above) whilst others changed a lot through the process of realising them in three dimensions. The puppets are made from a mixture of materials including found objects, wood, paper and fabric. I’m not a great admirer of clean-looking stop motion, it loses the essence of this medium for me which is its inherent tactility and materiality and for Salvation, I wanted a very rough-hewn, sculptural look to the puppets but at the same time, they had to be robust enough to last months of manipulation on the shoot. I worked with a couple of puppet makers to create the armatures and costumes and then I carved the heads and hands for all of them apart from the Woman who was probably the biggest challenge.

The Woman is the heart and soul of the film and I wanted her to operate in a poetic space where it could feel as if she had just emerged from a desert in Syria or simultaneously, from a forest in a Grimm’s fairy tale. There’s also a scale of naturalism and abstraction within the cast of characters; the Ringmaster is quite abstracted, more of an icon with strange shapes and form, and then at the other end of the spectrum is the Woman, who is the most ‘realistic’ looking character because this is a real experience for her and she carries a lot of the emotional weight of the story. Her head was made by Becky Weston who’s a brilliant puppet and model maker and did a great job of finding the right quality for the way the puppet looked. The puppets don’t have 3D printed faces or replacement expressions, they’re more like stage puppets, immortalised with one expression which has to carry many different emotions throughout the film. These emotions then are conveyed through the animator’s performances; the choices of movement, stillness, physicality and gesture, and of course, the voice acting.

The voice acting was something I wanted to ask you about as it really stood out as vital in the short’s success. Can you tell us a bit about your cast and how you got them involved?

In line with the theatrical leanings of the film, I wanted to reverse the Shakespearian trope of having an all-male cast and with Salvation have an all-female cast and specifically an all-female cast for whom English was not their first language. I wanted to enhance the feeling of the film being a folktale, a narrative that the audience was being told, by having a mix of nationalities and accents that the viewer almost has to lean in and listen to.

I had a couple of actors in mind when we began production, one being Elisabetta Spaggiari who plays the Ringmaster. Elisabetta is an amazing theatre performer who I’d met in Paris and I’ve always loved her voice and wanted to put her in a film. Elisabetta did some early recordings with me for the teaser trailer and her voice became the hook from which to hang everything else on. Then Loran Dunn (Delaval Film), the film’s Producer, brought in Casting Director Heather Basten to work with me. Heather was brilliant and we talked about the tone of the film; the drama, the subtle element of black comedy, the desire for it to feel like an allegory and to have a range of accents and she arranged a great deal of readings from various different actors and also came with suggestions of more high profile actors for the roles of the Priest and the Woman.

Itziar Ituño who plays the Priest had been in a show on Netflix called La Casa de Papel (Money Heist) and played a character who was leading a dual existence; professional and personal, public and private – a duality which created a turmoil which was exactly what I was looking for with the character of the Priest. Salvation is Ituño’s first English language role which was challenging and exciting at the same time. And Yasmine Al Massri who plays the Woman appeared in the Lebanese Cannes favourite Caramel (2007) and played identical twins in the ABC show Quantico. Born to a Palestinian father and an Egyptian mother, Yasmine grew up as a refugee in Lebanon and often picks her projects based on their message. Alongside her work as an actress, she is a human rights advocate and she has been an incredible collaborator and advocate for the film.

I know stop-motion is your chosen medium, but it feels particularly suited to this narrative. What do you think the design and the tangible nature of the puppets add to the story’s impact?

That’s really wonderful to hear. I think I’m always conscious of the choice to use animation. Having done theatre, live-action, and other mediums alongside animation in the past it always feels like a great privilege and a simultaneous burden to tell a story like this in stop-motion. Salvation Has No Name is the biggest film I’ve ever made, it’s the longest and the most ambitious; seven characters, fifteen different locations, heightened production values and cinematography. It was always intended to be epic. But epic on a shoestring.

I just love that about animation, it’s a lie that tells the truth.

In the end I think stop-motion has an arresting capacity to it; we can tell, as viewers, that we are watching real objects move around on-screen, real puppets with real textures interacting with real props under real light. There’s something weighted about that. With that, I think you’re able to explore drama in a way that matches live-action’s possibility of empathy, but at the same time, you’re operating in a poetic realm. I just love that about animation, it’s a lie that tells the truth. I don’t think we see it used enough in this way. I would love to see more stop motion dramas that are adult pieces for adult audiences, and ones that don’t adopt a childlike aesthetic, films that employ a sophisticated visual language that would appeal to an adult audience.

Although the majority of the film is in stop-motion, it’s punctuated by biblical imagery and the odd section of cut-out animation, what was your thinking behind including these in Salvation Has No Name?

So on this discussion of technique, this was another goal of the film; to mix media in this way. I’ve always been interested in mixing techniques, I love Švankmajer’s approach who for me is the master of mixed media. I knew early on with Salvation that I wanted to combine techniques to tell different parts of the story in different ways but I was originally considering having live-action and puppet animation as I felt like these two mediums sat well alongside each other. Then I had this realisation that my career as a director was almost, aesthetically speaking, severed in two; one side being this sculptural puppet animation, and the other being a found-image collage approach. So it seemed like a good opportunity to pull these two disparate techniques together and use cut-out animation, exactly as you say, to punctuate the main narrative with flashbacks, internal thought processes, desires and imagery which generally operates on more of an abstract, subconscious level.

The structure of the script is actually loosely inspired by the ten plagues of Egypt.

I looked at a lot of religious iconography and narrative references when developing the film, it was something that I wanted to subtly integrate into the storytelling. The structure of the script is actually loosely inspired by the ten plagues of Egypt and some of the film’s imagery was also drawn from that. Because of the character of the Priest, I wanted to have the gravitas and theatre of these Biblical images scattered throughout the film. Because the story-within-a-story is told in black and white and the cut-out animation is also black and white print, the two languages ended up sitting really well next to each other. The imagery in these cut-out sequences mostly came from these 19th-century pictorial archives which are the same books Terry Gilliam often used for his Monty Python animations.

Talking of being inspired by Švankmajer, I was actually lucky enough to work with Ivan Vít who was a camera operator on Švankmajer’s Dimensions of Dialogue as well as collaborate with Alfons Mensdorff-Pouilly who is Czech director Jiří Barta’s long-time animator. We did a co-production with Animation People studio in Prague so I was blessed with this amazing team of Czech legends although due to Covid it was all directed remotely during the lockdown as I couldn’t get to Prague!

As you just mentioned, the short fluctuates between colour and black and white, was this planned from the beginning or something that happened more organically in post? And can you explain your decision behind this contrast in styles?

Yes this was planned in the early stages. I can’t exactly remember when or how it came about but the initial references I talked about earlier were either starkly monochromatic (the early photographs of Horst P Horst, films like F.W. Murnau’s Faust) or they were boldly colourful (Alexander Calder’s Circus, Picasso’s theatre set designs). So in my head there was always colour and black and white swirling around.

It’s quite a simple device and certainly not original (Nolan’s Memento comes to mind) but it was a neat way of differentiating the storytelling spaces of the ‘storytellers’ (in colour) and the story itself (in black and white). It’s a way of orientating the audience quickly and it also framed the story world, like it was an old film or a fable or folktale.

Like many films that saw the light of day in 2022, the production of SHNN was disrupted by the Covid pandemic, can you give us some insight into what that was like and the effect it had on making your short.

Making this film felt like a mythological odyssey. Producer Loran Dunn and I used to joke that the film was cursed, that the biblical plagues of the film were somehow coming true in real life! It was the longest and hardest film I have ever made and almost everything that could have gone wrong did go wrong! Like I said it took a long time to finance and we faced a lot of rejection from funders due to the subject matter and the negative religious undertones. The puppets were quite delayed in getting finished due to refining the materials and techniques for the costumes but we eventually got shooting at Aardman Animations early 2020 and had just gotten into the swing of things, finding our rhythm, and then Covid hit and we had to completely shut down the shoot.

It was a very terrifying and weird time but I was grateful to have Salvation to give a focus in that period.

Stop motion has relatively small teams but it’s similar to live action in that it’s crews of people on a physical set, interacting in close quarters. So we paused the shoot, ran a Kickstarter to recoup costs and enable us to rent a new studio space after we weren’t able to return to Aardman, we remotely shot the cut-out sequences in Prague, re-wrote the script, improved the storyboard, edited all of the voices and finished all the puppets! So it was a very terrifying and weird time but I was grateful to have Salvation to give a focus in that period.

Ok, final question, what’s next? I’m assuming it’s all promotion and festivals at the moment, but do you have any new projects in the works?

There are a few things floating around at the moment. I’m making a new very short film which will be a live-action puppet piece with the incredible designer and maker Cat Johnston and cinematographer Malcolm Hadley (there, now I’ve committed it to the internet I have to make it) and I’ve also written a new script which I’ve been pitching around and is intended to be an animated feature. It’s early days but it builds on what I was doing with Salvation in terms of adult storytelling, nuanced characters, complex themes and big worlds. After the trauma of making Salvation it’s taken a while to get my creative brain whirring again but there are definitely stories I want to tell, artists I want to collaborate with and techniques I want to play with. The biggest hurdle is trying to get people to finance it all but watch this space!