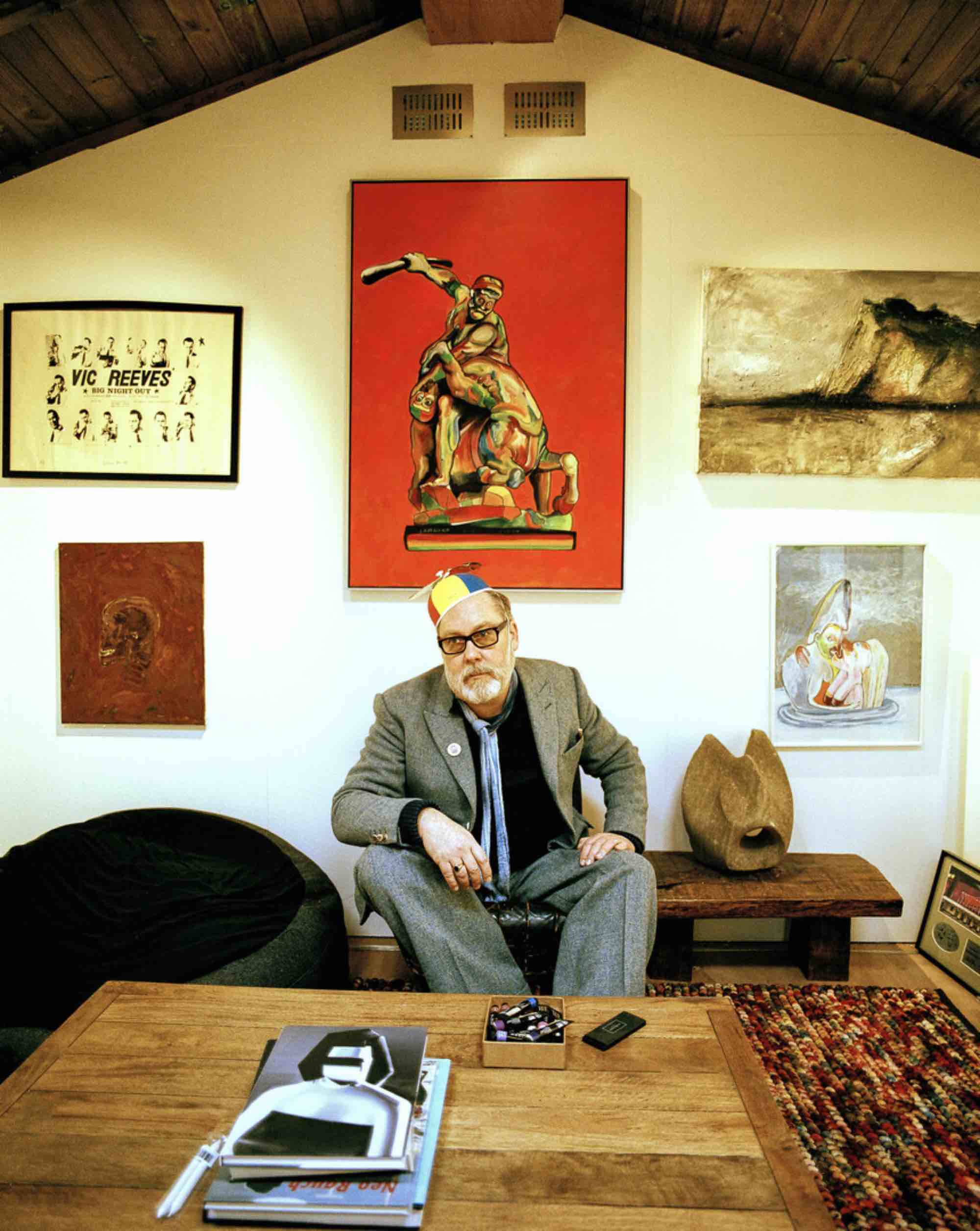

A Brush With Comedy, the debut feature documentary from filmmaker Louis Moir, explores the relationship he has with his father Jim Moir, AKA Vic Reeves, through the lens of the latter’s creative output. It’s a film which playfully interrogates the relationship art has with comedy historically, highlighting where they overlap whilst examining how they are often seen as diametrically opposed. In addition to his father, Moir also interviews comedians Spencer Jones, Bec Hill, Miriam Elia and Simon Munnery who each incorporate various forms of visual art into their comedy. With the film available to watch on Sky Arts, Now TV, and Apple TV, DN caught up with Moir to discuss his four year journey making A Brush With Comedy, from its origins as his graduate short at Arts University Bournemouth through to the challenges of sifting through the footage to structure the edit.

I read that A Brush With Comedy is an expansion of short you made at University. What initially drew you to make that film?

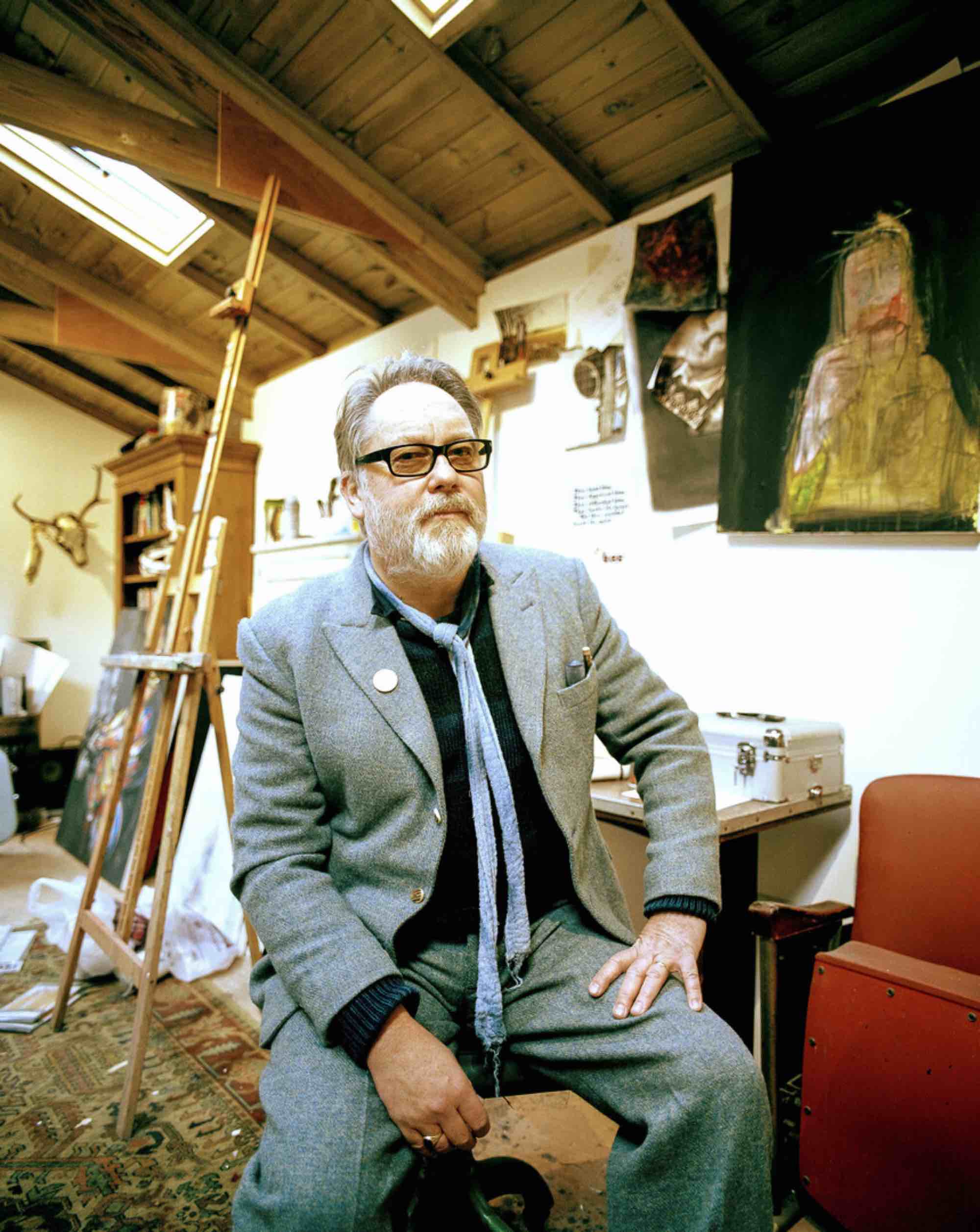

The film is based on my graduation film I made at the Arts University Bournemouth of the same name, which focused solely on my Dad’s process. I took the short on the film festival circuit and it was nominated for an RTS Southern Area award. I always liked the idea of working with people who fuse art and comedy because I grew up so close to those two themes. I was interested in this grey area between two areas of creativity that are rarely linked and at times looked down on. My dad always engrained the philosophy that creative thought and practice are not defined by theme or form. If it’s a funny story, a film, a painting, or even food, it’s all art and everything should be treated equally.

I wanted to trash those notions and communicate to an audience that art can be funny and that not all art should be serious, complicated or worthy.

Was there a moment or an encounter specifically that inspired you to explore the overlap between art and comedy?

I think what also helped the idea form was the, at times, portentousness of creatives I met or knew of at the time, either in education or the industry. If you were an artist you had to be serious and brooding, talk about work that was ‘in’ at the time. I wanted to trash those notions and communicate to an audience that art can be funny and that not all art should be serious, complicated or worthy. This idea stuck with me and after I made the short film I knew I could explore the narrative further.

Debut features are tricky beasts to get funding for. Do you mind sharing how you sourced the resources to make A Brush With Comedy?

Post university I was privileged to be invited to a Studio POW screening in Soho of their most recent feature, at the time, Cordelia. I got chatting to producers Kevin Proctor and Perry Trevers about my film and my ideas for expansion. They took on the project and funded me to make the feature, as well as mentor me. An amazing opportunity that I am very grateful for, especially in an industry that is one of the most competitive in the world. I still work at Studio POW to this day.

From watching the doc, it seems like you were with these people over a large span of time. How long were you working on the film for?

The production took place over four years, but this is mainly due to COVID. We shot around a week with each subject with James Gough who lensed the project, a sound recordist, runner and producer. Myself and James bonded over Charlie Paul’s art documentaries in pre-production. Mainly his 2019 feature doc Prophecy, which just brings to life Scottish artist Peter Howson’s work in a way that has a lasting effect on the viewer.

So much of the film is you in person with your dad and these other artists. What camera equipment did you use to be able to be so mobile?

We used a mixture of cameras, FX9 and c300 mainly, but Black Magic, and A7S for a second unit as well as GoPros and an old VHS camera I found in my Dad’s office. While the project was in post, I went back and reshot with all the subjects on my own to fill in the gaps in the narrative. All archive was shot on 8mm film.

I was interested in this grey area between two areas of creativity that are rarely linked and at times looked down on.

Given that you were shooting on and off for four years, how much footage did you amass? And how did you find the process of structuring it all in the edit?

We amassed a lot of footage over the years, with the shoots, but also archive, VHS footage, stills of the paintings, lots of stuff in different mediums. We were editing as we shot the main chunk of principle photography, with our editor Evelyn Fahey. The process that worked and continues to work for us was shooting the main segments with a small crew and re-shooting on my own as we edit to fill in the gaps in the narrative. I keep a log for all the rushes which Ev cross-references as she edits. I find the editing process challenging, but it’s where the narrative forms so we both become a tad obsessive.

How did you come across Spencer, Miriam, Simon and Bec? And what was it about them and their work that made you want to have them be a part of the film?

I found the contributors, apart from my Dad, obviously, through research and talking to comedians and artists. Spencer was suggested by United Talent Agency, they heard I was making the film and thought it would be a good fit. Spencer is naturally really funny, and his work is a form of avant-garde theatre, even though he wouldn’t admit that. Miriam I was introduced by her best mate Jessica Hynes who when she’s not acting is a talented painter.

Bec I saw at a PBJ comedy night and thought her flip charts were hilarious and unique. She also had a lot of imitators online and I knew she was one of the first to make these gag-based flip charts to music which was something I wanted to include in the film. Simon Munnery is a genius, and I think one of the finest comedians the UK has ever produced. His lack of mainstream success is both a shame but also a testament to how true he is to his art. I always found his work more akin to performance art than stand up comedy, I found it mad that no one had looked at his work from a filmic perspective.

What motivated you to become a documentary filmmaker?

I like the freedom and intimacy of documentary film. With scripted work, you need a crew, actors, and all that stuff but with docs, all you need is a camera and a subject. That’s really cool. It probably helped that being creative was very much encouraged by my parents. Sometimes having motivation isn’t enough, but I was lucky to be supported by producers Perry and Kevin who believed in me and the project. Their support and guidance channelled my motivation into creating something tangible.

Have you begun thinking about what your next film might be about?

I am making a documentary at the moment which is an anthropological look on small island culture. That’s being made with Studio Pow where I work full-time.