Set in the rural outback of South Australia, Matthew Thorne’s The Sand That Ate The Sea is an intertextual document linking the memories of a young boy’s absent father with the onslaught of a foreboding storm. Thorne utilises poetic imagery to steer the audience through the boy’s experience whilst taking in the majesty of the outback’s grand landscapes. DN is thrilled to present the premiere of The Sand That Ate The Sea online today, accompanied by a chat with Thorne about the making of his elegiac work.

The Sand That Ate The Sea is filled with so much striking imagery, was there one particular image that started everything off?

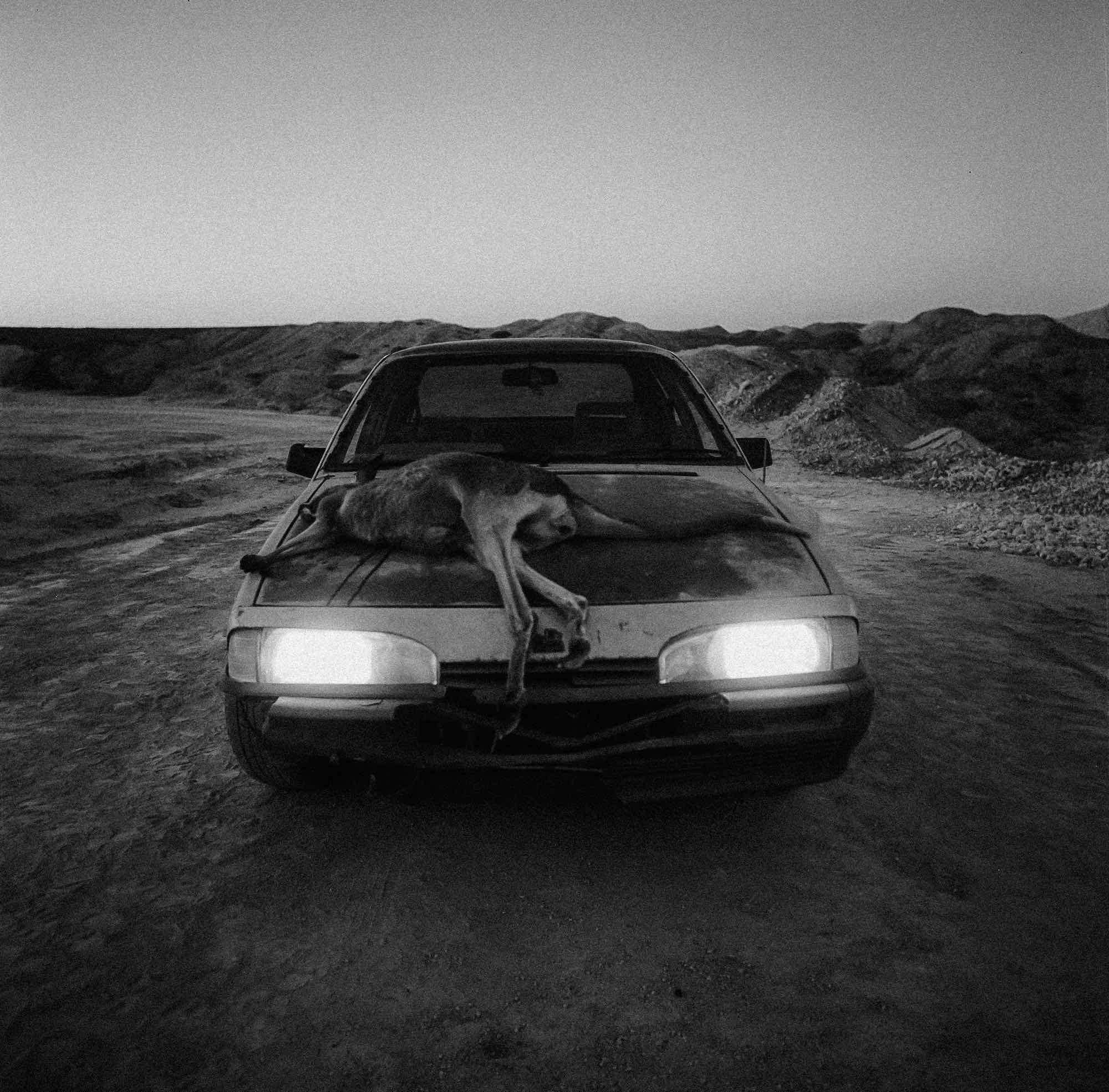

The first element of the film came from a dream six years ago. I woke up with this blistering image in my mind of a Holden sedan burning on a salt flat. That opening scene was the first image I wrote down, and that formed the spark that grew out into this story about time, fatherhood, familial grief, and the unexpected death of a father.

The idea of telling a story that was lost within a cohesive internal magic, where the boundaries of our world were tested was exciting to me.

At the time I was also deeply absorbed by the work of the magical realists (Allende, Marquez, Jodorowsky, Tarr, Rulfo and Fellini) and so I think the idea of telling a story that was lost within a cohesive internal magic, where the boundaries of our world were tested was exciting to me. There was a certain coincidental power in what happened in the making of the film too. At the point where I started writing the script I had never been out to Andamooka. I just knew I wanted to tell a story about those elements out in the desert where I had spent some of my childhood. In that mystical landscape.

It’s interesting what you say about testing the boundaries of our world narratively and how that bled into production, were there some particularly serendipitous moments whilst making it?

I wrote the title for the film, The Sand That Ate The Sea, long before I knew anything about the formation of Opals; how they are created by the silica and sand of these ancient sea beds that form the inland deserts of South Australia absorbing the water from the sea that sat above it.

The year before we went to shoot the film, my father died of a sudden and unexpected heart attack and disappeared from my life, in a mirror to what happens to the young boy in this film. It was that event I think that galvanised me to put the film together. The process then was just one of living in the community and developing the work with them, and with the unique character and story of that land and community.

How does making such an evolving film affect preparing for the shoot? What did your crew make of it?

Producing the film was especially difficult because of the remote locations and the incredibly minimal budget we had to work with. So in many ways, it was a journey of reframing the project to the crew as not being just a traditional process of making a film, but being something different, something more akin to art making. An adventure together into the outback heartland of Australia. In the end, I think many of the elements in the film that are the most compelling come from the freedom of that approach and the way that embedded us deeply and honestly into the community.

Given the remoteness of your shoot, were you conscious about impacting the local community?

Andamooka is a very special and beautiful community. I never feel more in connection with my Australian identity than I do when I am there. It really is the frontier, and the frontiersmen still call it home. My only hope with this film is that it does some justice to the beautiful and terrifying power of that landscape, and the unique character of that community.

How does your photography experience transfer to this kind of artistic narrative and visual storytelling?

It’s interesting because the first ‘whole’ photographic project I ever shot was made in tandem with this film. Before that, I had always taken photos during directing as a tool or guide but never seriously with the intent of exhibiting the work. I had never before this project really considered myself a photographer. I was always first and foremost a director.

The hardest reality of cinema making I often find is the simple scale of it.

That said, I suppose it was a natural and easy transition from the world of photography. I think very visually in my work, not out of pure fetishised aestheticism, but out of a connection with the underlying ‘metaphorical’ language of images.

Do you see yourself continuing to work in both forms?

The hardest reality of cinema making I often find is the simple scale of it; the moving parts; the many people; the giant monolithic construction that has to whir and grind into life to see out the vision of this small creative few. It is incredible any great works of art get made through a process that innately requires so many disparate hands.

When you come from that lens of creation, photography is a very simple and fulfilling art form. It is simply you, the camera, and the world before you. There is less to adulterate that relationship between your internal vision and feeling and the world outside of it. I think that is what keeps me in photography now; learning how to connect that back to filmmaking, and find a process that is as innately connective between subject and intention. That is the bridge that brings me back to cinema.