A man sitting on a dock. Overhead shots of oceans. Clouds forming. The short but sweet Flow with Life, made to celebrate the water-resistant textures of Canadian clothing brand Arc’teryx, explores all the different textures of water in an intimate, immersive fashion. We talked to Director Adam William Wilson about the project, working with the luxury of time, and his relationship to Arc’teryx’s clothes.

How did you get involved with the project?

It was the beginning of lockdown in Canada. A friend and I were locked in a cabin in Northern Ontario and we thought it would be a good opportunity to make a film that really related to what we were doing out there. We were kind of stuck and took the time to become more connected with nature.

What inspires you about Arc’teryx clothing?

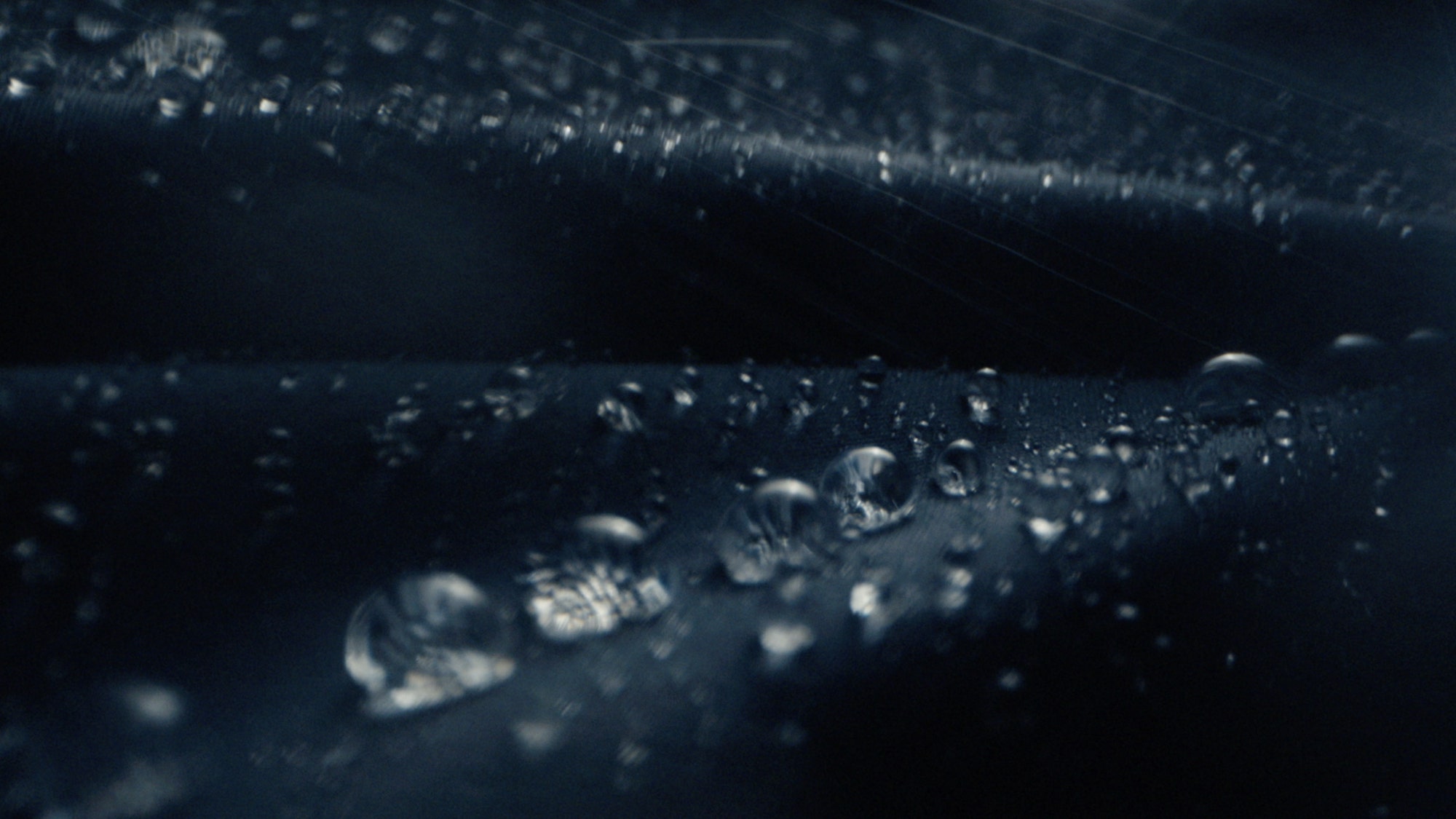

I’ve purchased their clothing for a few years because it’s one of the premier brands for working in the film industry in Canada. The clothing and the material are so precise. It’s this luxury outdoor brand, and when you get into the macro world of those materials, it is so beautiful. The idea was to take the materials and photograph them in a way that mimics the natural world. We wanted to get close to the material to understand a little bit more, pairing that with macro images of skin and telling the story of that material becoming a second skin.

I thought this film would be a love letter to water.

How small was the crew?

There were only two of us and we shot for nine days. It was hard because we were doing everything together. We recreated underwater scenarios inside a small studio space in the cabin. But doing all the product shots with two people is difficult as you need someone to work the material and you need someone to pull the focus so it takes twice as long. If you’re shooting ratio is not the best, you have to shoot a lot. It was difficult, but certainly fulfilling.

The film features all these different representations of water; rain, ocean, clouds, shower water, fog and condensation. When starting the film did you think about all the ways you could represent the element?

I thought this film would be a love letter to water. Water is that element that really allows you to connect with nature. It’s such a big part of us and our environment. I thought if we could represent that in all of the imagery and really focus on the flow of the water, and all the different personalities of the water. We shot hours of footage of water so that we had different textures and magical elements. Then certainly how water exists on the Gore-Tex Arc’teryx material, which has this kind of hydrophobic quality.

As a creative you need to just lean on people to take it where it needs to be.

The star of the film is often vulnerable, with his shirt off. How much did you want to present the clothes as being a kind of second skin?

The intention was to present a different kind of outdoor gear film and really focus on the vulnerable man, which is why we really focus on the skin and the goosebumps on the back and the beads of rain. I wanted to let the audience know that you can have as visceral and vulnerable an experience within the Arc’teryx gear as you would within your own skin. This gear allows you to stand in the rain and have the water beat off of you and be immersed by that soundscape.

This immersion is also stressed by the sound design. How did you want to use sound design to stress this experience?

In the editing process there was this back and forth between what is an experience happening now and what is a flash of the past. The underwater stuff, for example, ends up being in that world of memory and experience. I explained what my intention was to the sound designers at IXYXI and they just did their thing. They’re quite brilliant. As a creative you need to just lean on people to take it where it needs to be. My intention was to make a film that felt intimate and connected in a fresh way. They made it feel connected. One of my favourite parts of the piece is the sound, as even when you close your eyes you can really feel those raindrops popping in your ear.

Having all this time allowed us to look at the footage every night and watch it on a big projector screen in the cabin.

The film also mixes aspect ratios and colour schemes. What was the idea behind this different breadth of cinematic languages?

It ends up being this sort of montage film. It goes back and forth in time, so the aspect ratio was used as a tool to help us define moments that are more of a memory. Then we shifted the colour in spaces where you go underwater — those are flashes of a time past. Then when you’re above ground in sort of real time you have the saturation of colour and more dramatic images.

It seems you had the luxury of time to work on the shoot. How did it influence the process?

When we were shooting, having all this time allowed us to look at the footage every night and watch it on a big projector screen in the cabin. We were really able to dig into the details and figure out what type of footage we wanted. So it became more of an organic process, very different from any commercial filmmaking where you’re really stuck for time. We were able to organically go through the footage and assemble that imagery while the shooting was happening.

Are you working on anything at the moment?

I’m working right now on a short dance film. It’s footage I shot last year of a friend of mine dancing in this beautiful laser light space. I’m creating a film about his creative process and his story of becoming a performer, and how he has learned to be able to take his emotions and transfer them into these physical, gestural forms with his body.