Hannah Brewerton’s Hit and Run – created as her graduation short from the Royal College of Art – may be specifically focused on the politics of distraction used in the 2019 general election but its showcase of shaky responses and casual dismissal of perpetual failures is perhaps even more resonant in the wake of the UK government’s response to the pandemic. Brewerton crafts her caricatures of key British political figures with wobbly lines and disgruntled expressions, perfectly capturing the tactical gameplay used to refute policy and deliver weightless slogans. DN is delighted to premiere Hit and Run on our pages today and speak with Brewerton about the inspiration she drew from political cartoonists when creating her short, how she channelled her political frustrations into art, and the decision to chose the very un-British arena of baseball as her sport of choice.

What drew you initially to create a politically charged satirical animation?

The film was my graduation project from the Royal College of Art. It started off as an area of research, I was interested in the use of graphic design by far-right political movements. This led me to the concept of shitposting and the idea of derailing rational debate/discussion. I started this initial idea development in the autumn of 2019 during the general election campaign in the UK. I then came across this article from the New Statesman about how the Conservatives were using memes, likening their use to a Soviet era weaponisation of information designed to “dismiss, distort, distract and dismay”.

I wanted to capture the chaos and confusion of a campaign and the still emptiness that follows the results, almost like a high-pitched ringing in your ears.

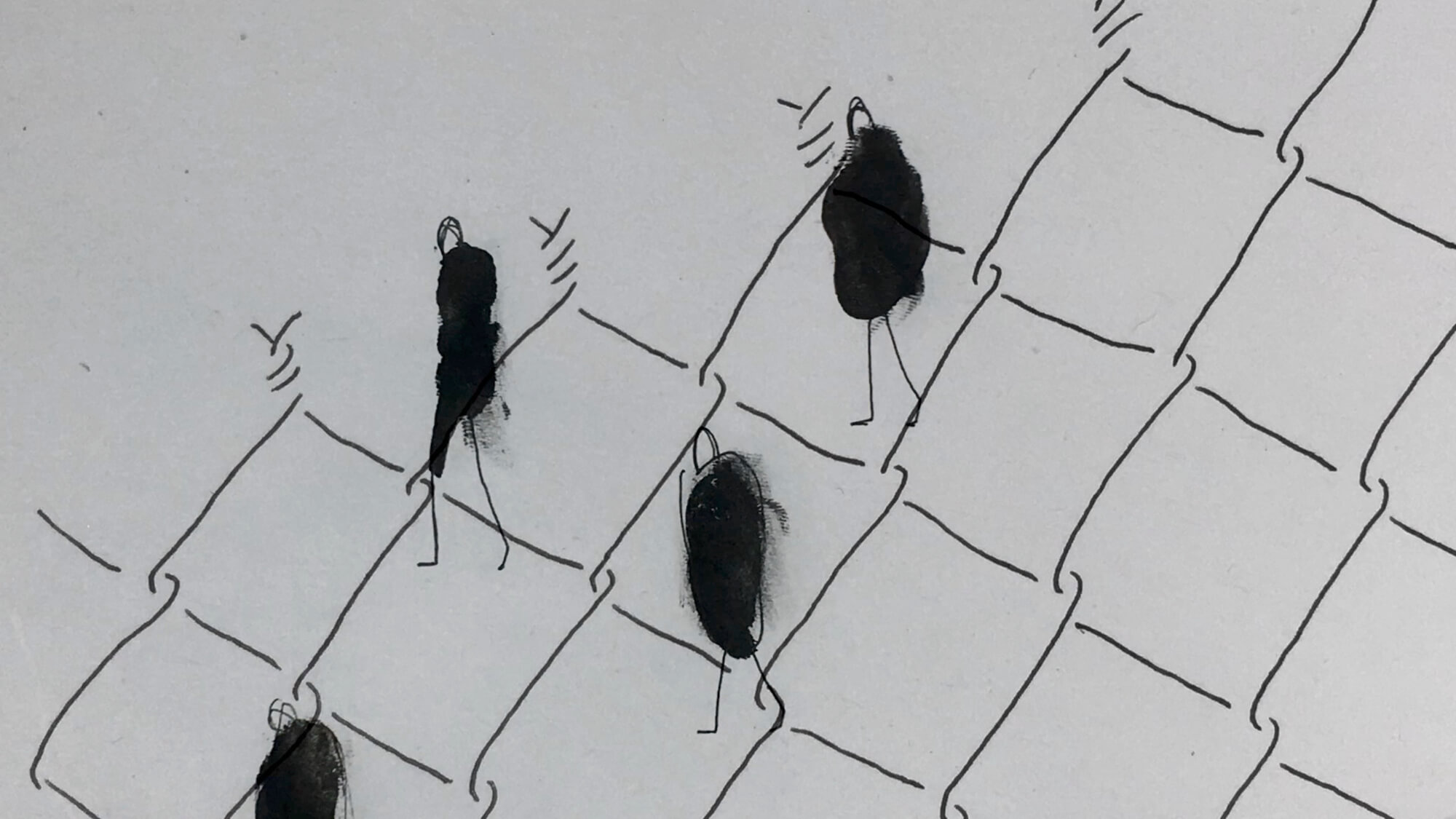

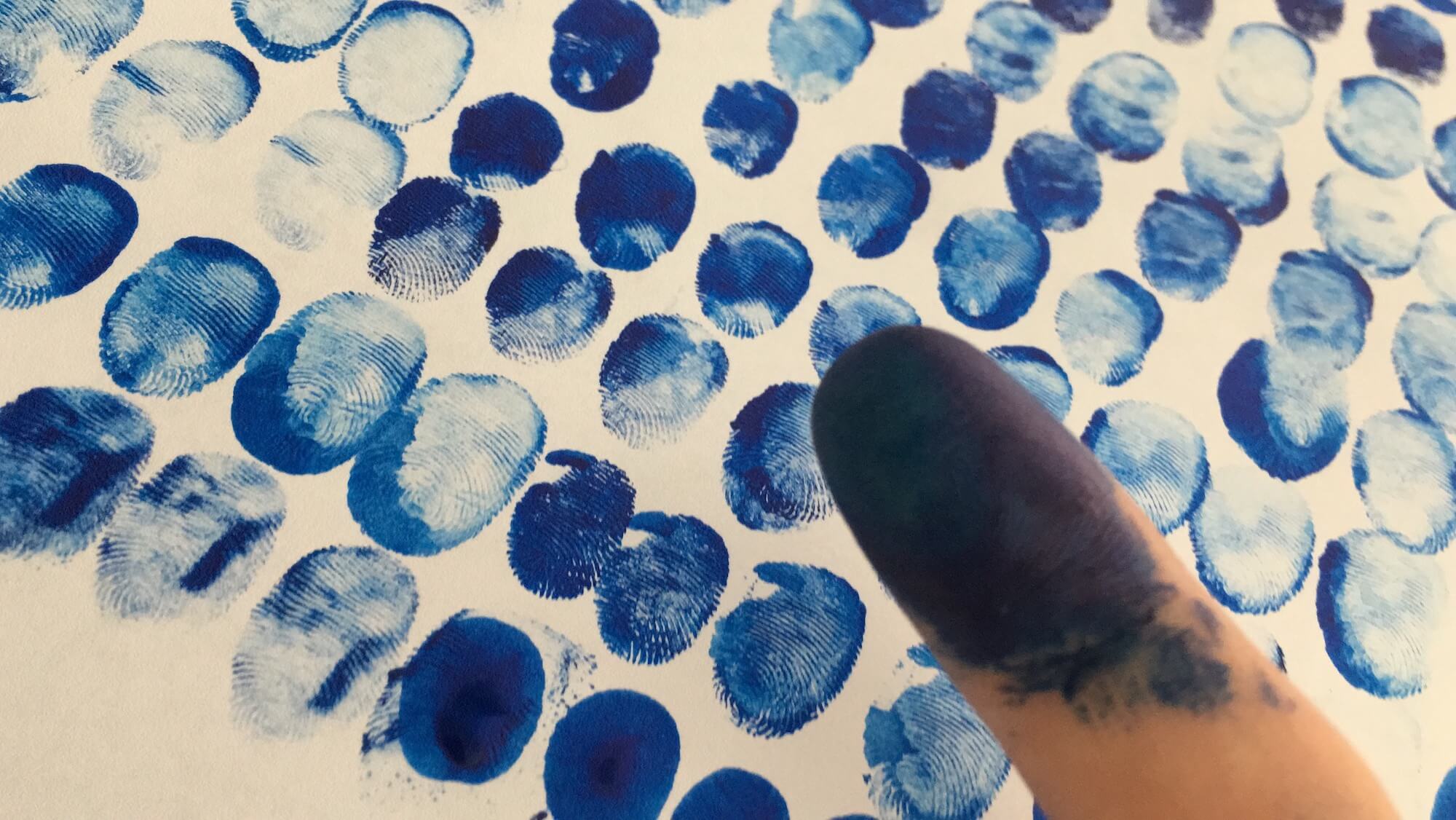

This idea of wilful distraction really resonated as I was seeing it a lot in the media, on politics shows, etc. and it was infuriating. Up until this point I just had my research, lots of abandoned scripts, and a load of experimental animation tests that I had been doing as a kind of meditation exercise after a day of staring at my computer, willing a film to emerge from the void.

I’m curious to know why you opted for baseball as opposed to a more typically British sport like cricket?

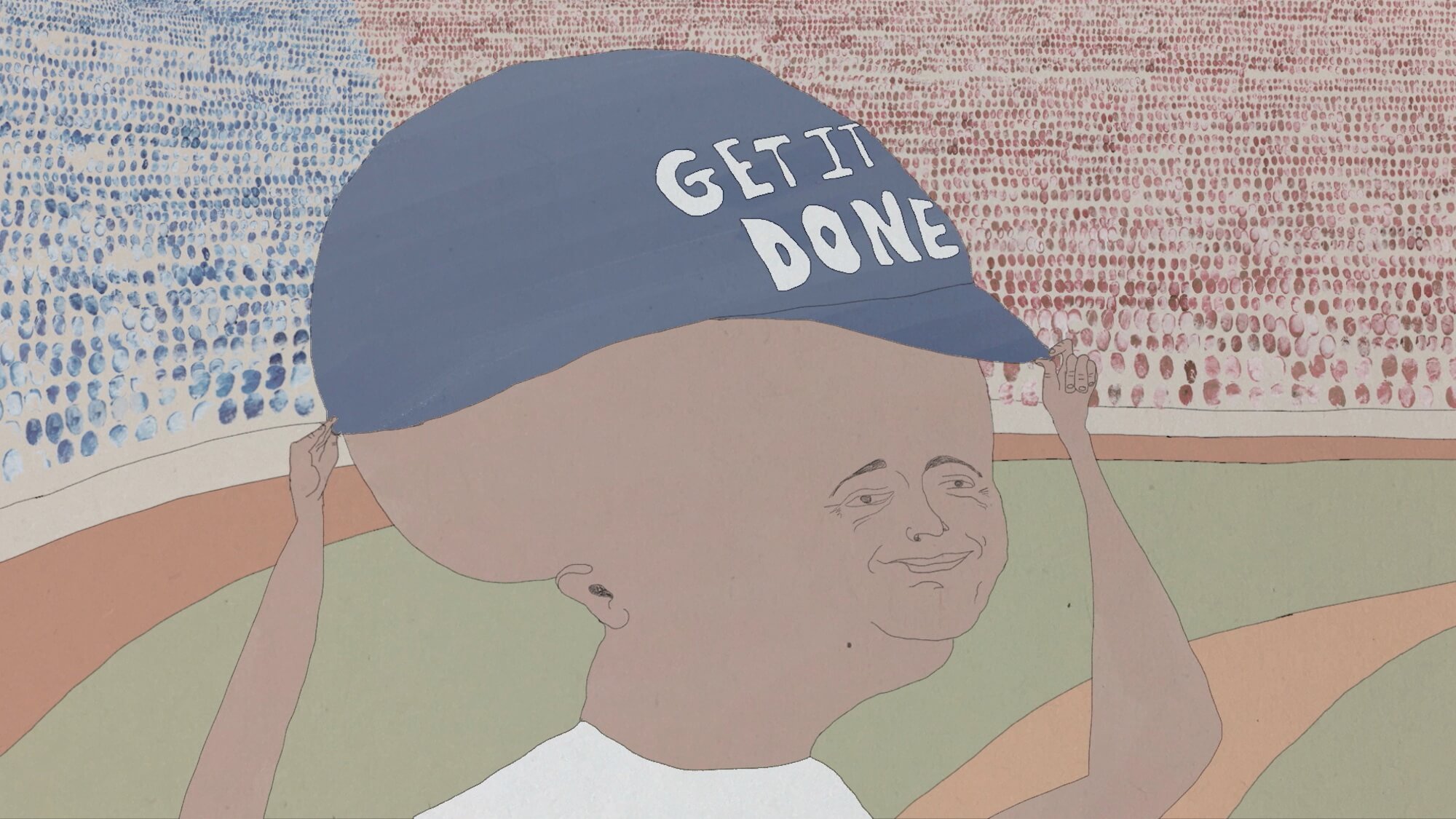

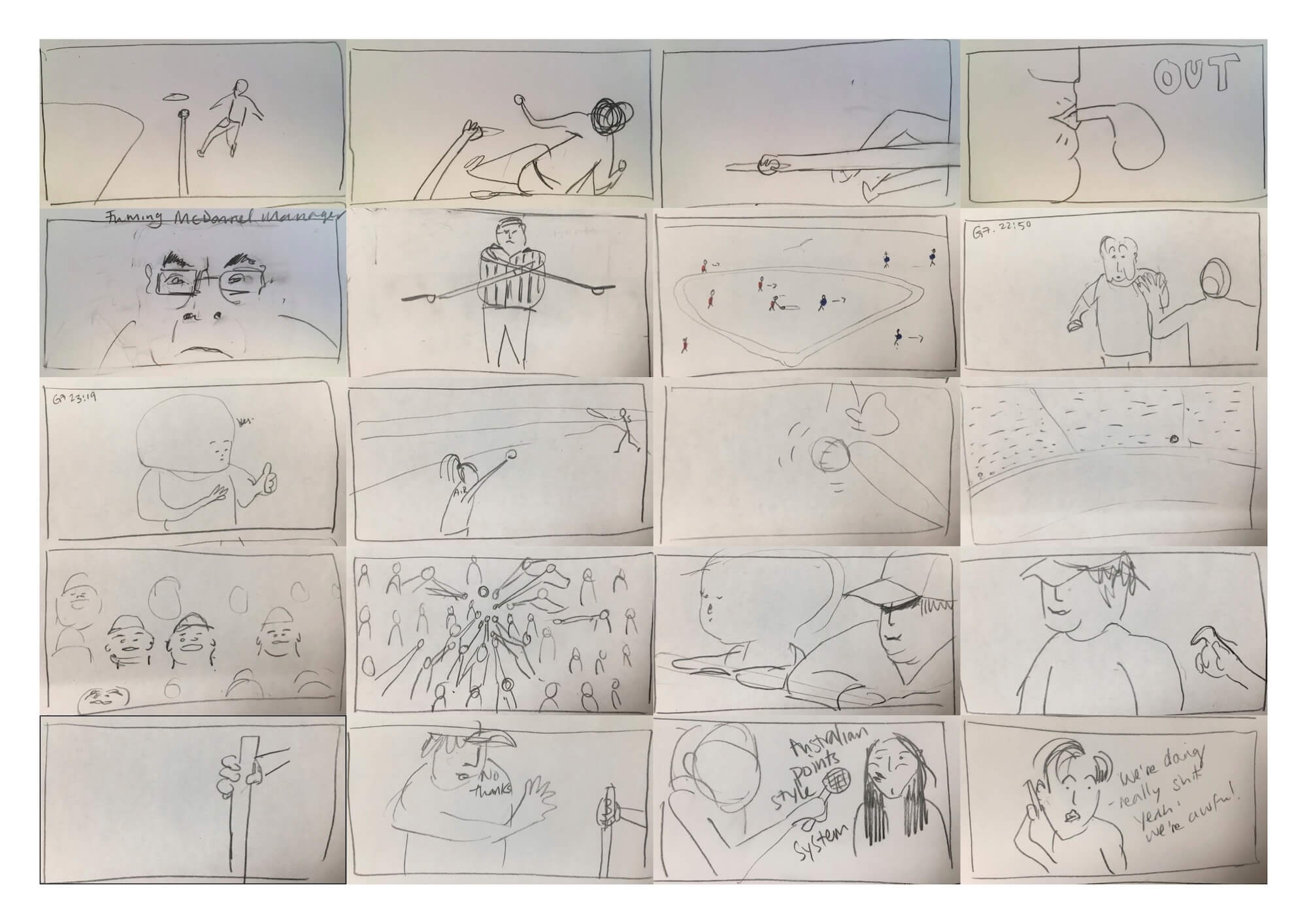

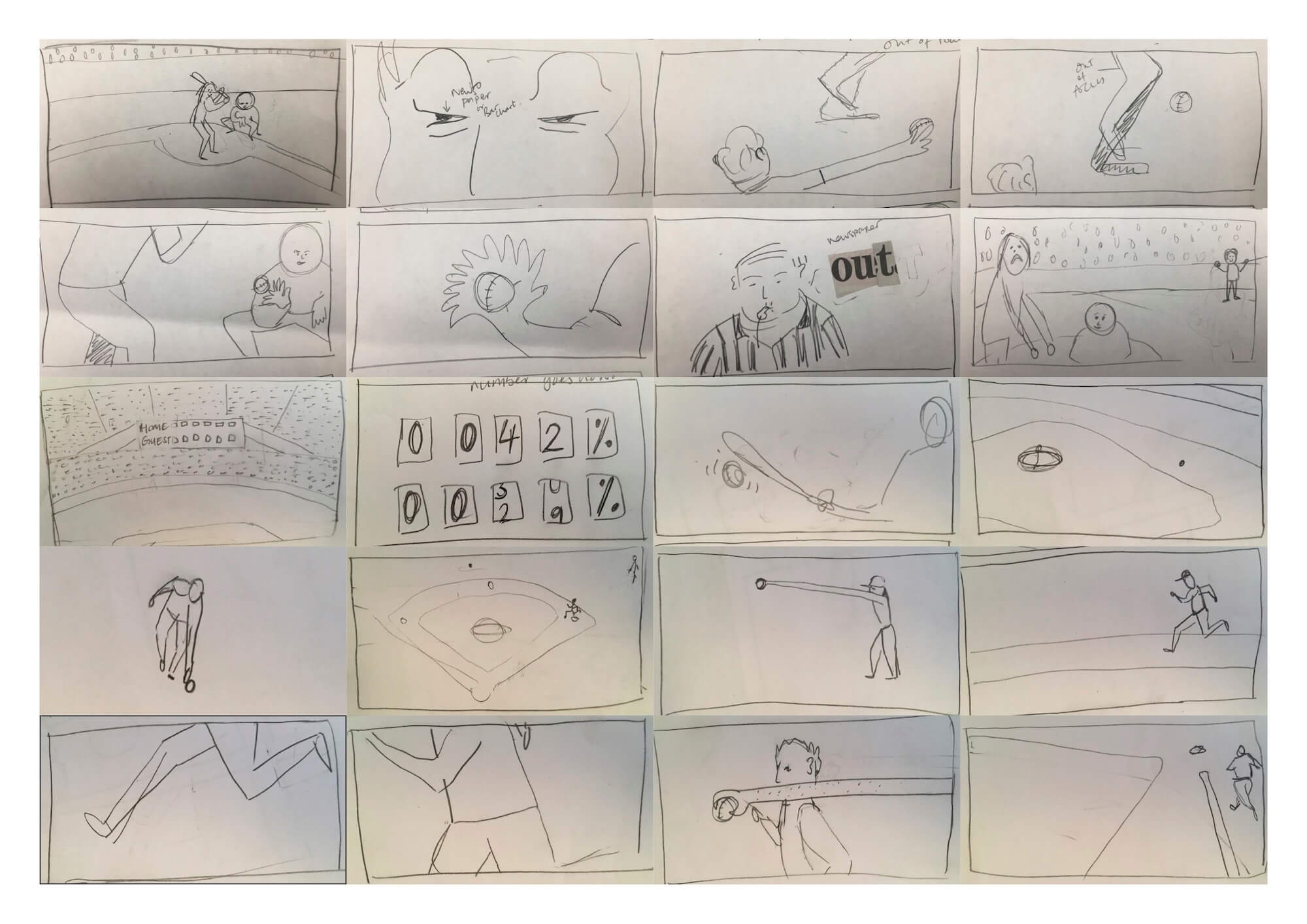

One morning just before the election I was listening to an interview on the radio with the then Chancellor of the Exchequer who answered the interviewer’s every question with the slogan “Get Brexit done”. I had just woken up and, still in a kind of dream state, this image of Sajid Javid with a massive shiny head drifted into my consciousness. In the image he was batting away policy questions as they were fired at him with a Brexit-blue baseball bat. It made sense to me that it was baseball, and not cricket because he was playing the same kind of political game that we had witnessed in the US a few years earlier and though the Conservatives stopped short of MAGA hat style merch, their campaign appeared to share almost identical tactics. The film’s narrative developed quite quickly after that.

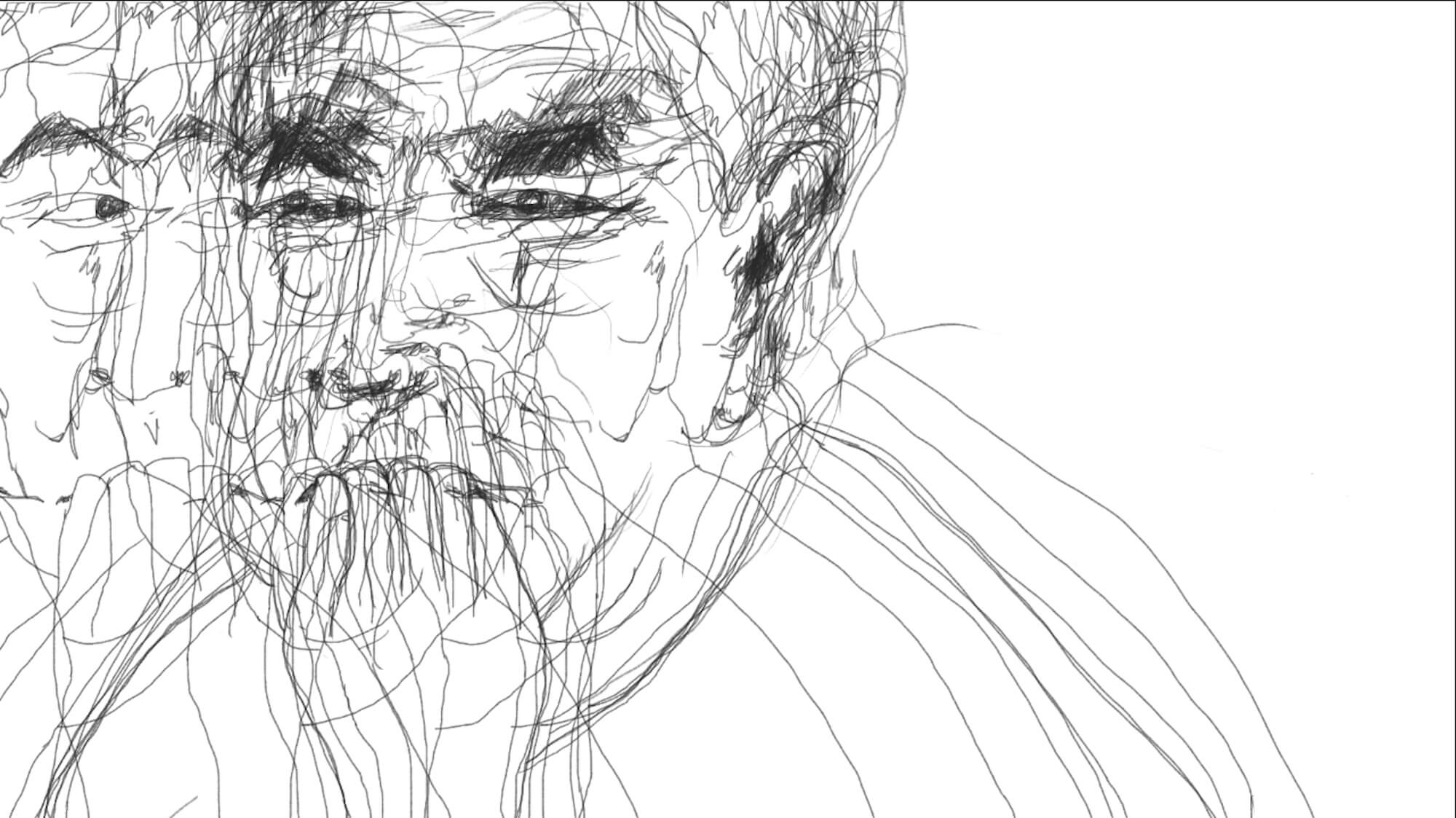

How challenging was it to caricature the politicians?

I had a lot of fun drawing caricatures of UK politicians and characters involved in the campaigns of the main parties. I was influenced a lot by political cartoonists like Steve Bell and satirist playwrights like Dario Fo and Pinter. I wanted to capture the chaos and confusion of a campaign and the still emptiness that follows the results, almost like a high-pitched ringing in your ears.

How did you take these ideas and drawings from paper to screen?

I made a very rough animatic and began animating the first scenes in Photoshop while continuing the straight ahead tests under the rostrum at the end of each day. Then in February 2020 a picket line was set up outside the college buildings in support of the UCU strike and a couple of days after the strike ended, as we were about to reconnect with tutors/peers the RCA closed its doors as a result of the COVID pandemic. I was lucky that I was working mostly on Photoshop and not too much of my film was stuck in the studios. Tutors were proactive and quickly found ways to support us remotely but for April and half of May I made pretty much no progress whatsoever.

It made sense to me that it was baseball, and not cricket because he was playing the same kind of political game that we had witnessed in the US a few years earlier.

Did you work with any collaborators during the process?

Throughout the production process, I was working with Sound Designer Al Hobson who was instrumental in getting me back to working on the film. He has an unbelievable amount of patience and enthusiasm and made working in isolation less isolating. Most of the film was animated in June and July 2020 and I had a lot of help from fellow students to finish colouring.

Aside from working remotely, what other challenges did you face as your course was coming to a close?

I don’t think I’ve ever worked such long hours for such an extended amount of time, ever. I finished the film at around six AM on the day the virtual grad show was due to open around the middle of July. There was a lot more I felt I could have done after the show to make the film better, a testimony to how much I learnt making it I think, but I was content to leave it as it was. Making a topical film like that with such a slow medium is highly problematic.

And how have the reactions been to the film?

With the global pandemic at the forefront of everyone’s mind, I wondered if anyone would even remember what had happened a few months before. The response has been really positive though, especially outside of the UK.

What were some of the key lessons you learnt whilst studying at the RCA that you utilised in Hit and Run?

There were a lot of things I learnt at the RCA. I had never animated before I started my MA, technical skills aside, I was always encouraged to experiment and try out new things, even if the result is abstract or unnaturalistic. I think that gave me the confidence to attempt difficult shots and movements. I remember when I was just about to start animating someone said I’d better be good at run cycles or I’d have a nightmare animating, and I thought well, I invented these characters and I can decide how they run, catch, jump, stand, etc. Of course it depends on what you’re using the animation for but I love seeing how fictional characters can lay bare the absurdities of reality simply by moving in unexpected ways.

What’re you working on next?

I’ve been working on a short film in collaboration with a friend of mine who’s a spoken word artist. It will hopefully be finished this summer but who knows, it’s been a bit of a struggle to be honest. Other than that, I’m experimenting with some VJ software and have a half plan to work on a live performance with a few musicians – one of whom is Al Hobson, who did the sound design for Hit and Run.