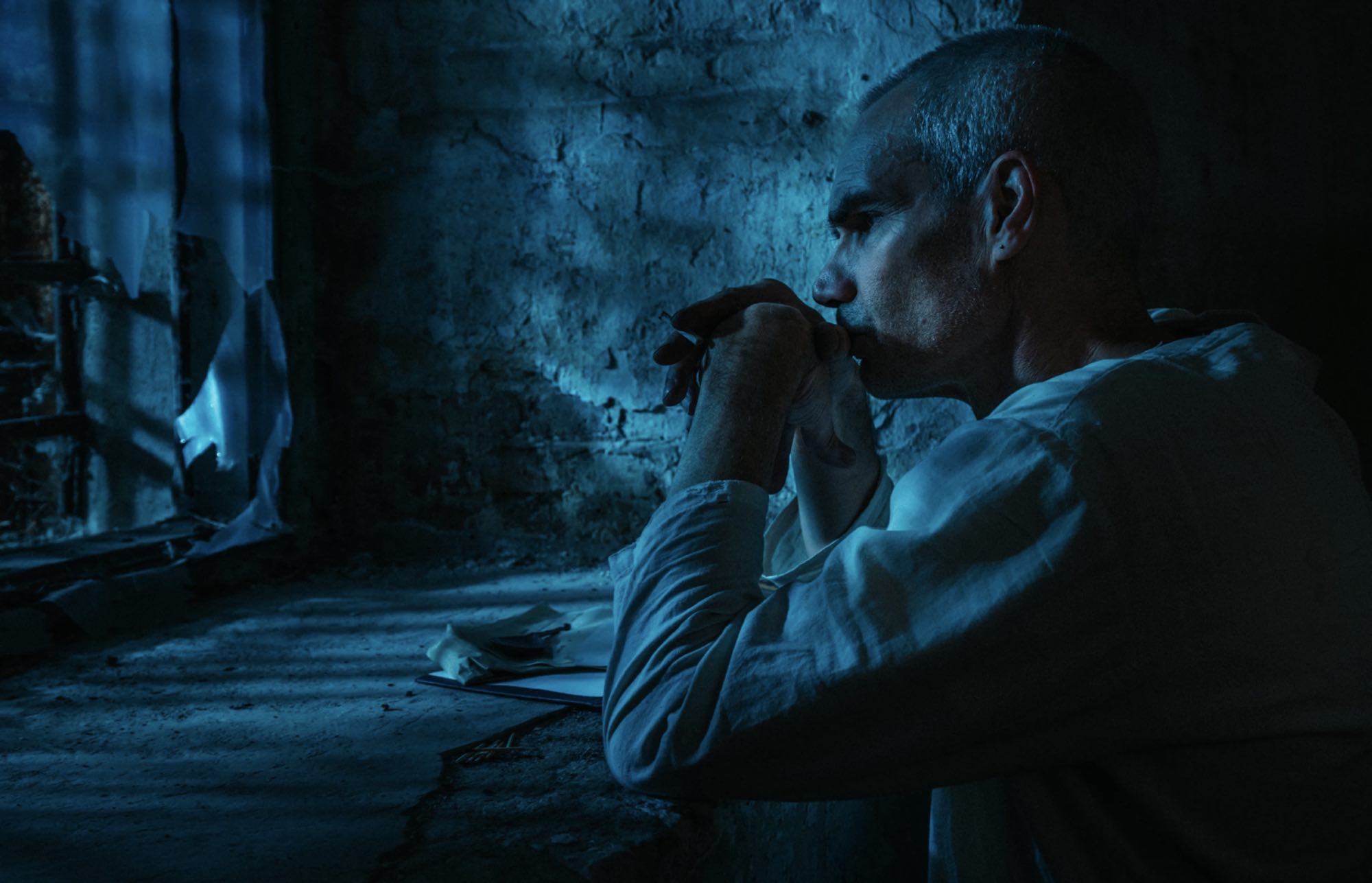

Having collaborated with Writer Frank McGuinness on a number of projects including their BAFTA-nominated short film The Stronger, Actor/Filmmaker Lia Williams returns to the director’s chair for another McGuinness-penned script in the form of JSB Films produced historical prison drama Samovar. The story is an imagining of Swedish Architect and Humanitarian Raoul Wallenberg’s life spent behind bars in a Soviet prison and the development of a tender relationship he forms with a fellow inmate, who recounts to him the impact of humanitarian actions. It’s a fascinating rendering of the prison life of a man who remains quietly defiant of a bleak and brutal world and DN is delighted to Premiere Samovar online accompanied by an interview with Williams about her ongoing working relationship with Frank McGuinness, the practical challenges of shooting alongside a working prison, and the empathetic understanding she has for the actor’s process.

What was the genesis of Samovar as a project? Did Frank McGuinness approach you with the script or was it your concept initially?

During lockdown, Frank and I were discussing how we might continue to work under the strange new restrictions, and he very generously offered to send me the script of a short piece he had written for the theatre, called Samovar, and suggested I make of it whatever I wanted. The moment I read the script I could see it. The words instantly created a series of paintings in my head and I knew I had to bring it to life. It was a fantastic moment.

We are always in some kind of conversation without words.

How would you describe your working relationship with Frank McGuinness?

Frank and I have worked together many times. He’s such a potent combination of poetry and visceral responses to the world as well as having huge intellect and biting wit. I feel I’m in the company of a true artist. I think he feels I can turn his words into pictures. We are always in some kind of conversation without words. We simply understand each other. We sense what the other offers or needs.

What is your process for breaking down a theatre script and preparing it for screen?

As a piece written for the theatre, the shooting script needed to be reimagined visually. This meant breaking up the flow of the dialogue into separate scenes. Clearly Samovar is set in a prison, but the first question was where exactly? Does it happen all in one prison cell or in a number of locations? Are there exterior scenes that would enhance the story, containing, as it does, references to birdsong? How much freedom do these men have? How observed are they by guards and other prisoners? Are there other prisoners? Are there guards? Are these two men actually alive? Are we in a magical realism or a dream state or a memory? But my first and easiest breakthrough was knowing immediately who to cast in the two roles.

How did you collaborate with Alex Lawther and Angus Wright on their performances as Anton and Raoul?

Firstly, we spent time discussing who these two characters are, who they were historically, how they might behave in each other’s company, what they give to and what they conceal from each other. Angus and Alex are hugely imaginative and sensitive actors who understood Frank’s writing intuitively and it was clear that, although they had never worked together before, this was going to be a fruitful, sensitive and honest working relationship. I had to say so little to get such beautiful responses moment by moment. They were superb.

Also, we collaborated with the brilliant Designer Jo Scotcher, who sourced authentic materials for their prison uniforms and shoes and for the sacking and thread for their prison sewing work. She also found evocative and authentic Soviet-era props such as Raoul’s cigarette case and matchbox, and the Russian graffiti (reproduced from actual Soviet prisons) on the cell walls.

What was it about the location of Fortul 13 Jilava that drew you to shoot Samovar there?

Our hugely talented Producer Jess Benhamou, having researched old prisons in the UK, was quick to realize that it would actually be more cost effective to fly to Estonia or Romania than it would be to shoot on location in London or Gloucester. And of course, much more historically powerful to shoot somewhere that could stand in for a prison or psychiatric institution in the Soviet Gulag system. Fort 13, in Jilava, is one of the few surviving 19th-century defensive fortresses that used to ring Bucharest and was used as a prison in the 20th century. It has a grim history. The Jilava Massacre took place here; a reprisal by the fascist Iron Guard movement who, in November 1940, executed 64 political prisoners in their cells. When you walk down the damp, dark echoing corridors, and into the ruined prison cells, you can feel the ghosts in the walls.

I knew the film had to create a kind of dimension of its own… a waiting room where these troubled souls hovered.

For Alex and Angus, there was a very real sense in which no acting was required to summon up the disturbing past in which their characters were forced to live and die. And for me, I could feel the ghosts. The air was thick. For all its horror, the rooms and corridors had a sad beauty to them. For the camera, it was exquisite. I knew the film had to create a kind of dimension of its own… a waiting room where these troubled souls hovered. This decaying prison trapping the characters in space and time.

How challenging a shoot was it practically? What hurdles did you have to overcome in the making of the film next to a working prison?

Yes, it was challenging. Even without the restrictions of Covid. Even without the delay caused by the deep flooding of the entire site that set our schedule back by three months. There is a modern working prison at Jilava, that shares the grounds with Fortul 13. As a result, there were many regulations to follow. When we arrived on set in the morning, we had to pass through the security system of a modern prison. This required leaving our mobile phones behind, waiting patiently until the prison staff had all clocked on for the day shift and clocked out for the night shift before we were each (unsmilingly) processed, frisked, and logged. It was, in the end, an added atmospheric bonus that came with the location. The process of being checked in and out each day provided a sobering reminder of real prison conditions.

If I could take them into their rich imaginations and encourage them along the way with all the support I could offer, I knew they would be able to put themselves in a precarious and emotionally challenging place.

You’re a multi-hyphenate artist who works across several art forms, how does your work in theatre, film and television inform your filmmaking?

I’ve always had an intuitive response to a story as a whole rather than any written character within that story. I see the big picture and that drives my choices and inspirations. As an actor, I live inside my characters, I climb into them and so I’d say I have an understanding of what actors might require psychologically in order to deliver, in this case, the intensity of performance required for Samovar. And in a short period of time in a very difficult location. I understood instinctively that although I asked Alex and Angus to limit what they ate for the month before shooting in order to look like prisoners that I needed to support them in that. The conditions were difficult on set. It was extremely cold; they were hungry and tired. If I could take them into their rich imaginations and encourage them along the way with all the support I could offer, I knew they would be able to put themselves in a precarious and emotionally challenging place.

As a film actor, I’ve always been interested in how those who work behind the camera do what they do and so it is not a huge distance to travel to go from one side of the camera to the other. I would encourage anyone who has an interest in either side of the camera to use any time they are lucky enough to have on a film set to ask questions and get involved in the astonishing skills that lie on the other side. Ultimately, it’s all creativity and requires an openness and a diligence, a sense of humour and a sense of seriousness and rigour.

What are you working on next?

Acting jobs next. I’m about to open in The Vortex, at Chichester Festival Theatre, the play that was Noel Coward’s first great success. I am playing Florence Lancaster, and my son in real life, Joshua James, is Florence’s son, Nicky. We’ve never acted together before so it’s slightly surreal but very exciting. It’s a brilliant play. After that, I shall be the head of an MI6 team, in the new TV series, The Day of the Jackal. I am also in conversations to direct in theatre again. I like to see how far I can spread my wings. My dream before I hit the grave is to direct a feature.