As a child who grew up wandering in and out of pubs waiting for my mother to finish her shift, I would have frequent encounters with the eccentric locals who, more often than not, chose to spend their time regaling customers with the same old stories, most of which were either embellished to the nth degree or completely fabricated. It’s these types of characters that lie at the heart of Sean Lyons’ tall tale comedy Smoking Dolphins, a pub-set short which takes these archetypes and finds the similarities they share with double-dealing politicians. Lyons has had great success with Smoking Dolphins on the festival circuit and we’re excited to now be presenting the online premiere for audiences worldwide. It’s clever, funny and really well-constructed, an element of the film we discuss with Lyon in our in-depth interview below where he also reveals the advice on blocking he received from James Mangold.

How did the concept for Smoking Dolphins come to you?

Smoking Dolphins came about somewhat serendipitously. I’d love to say it was initially written with intent and an objective but it was more a discovery and a realisation in the moment. During lockdown, I was sorting through some boxes in the loft and found a hard drive from university. On it was mainly terrible photos of drunken uni nights, but also a script, Writer James Powdrill had written back in 2009. Brilliant script, it was a riff on a conversation he’d overheard while working a bar during a biker festival. He’d written it up and sent it to a few friends at uni and we all loved it, though nothing ever came of it. When I came to read it again in 2020, I fell back in love.

I saw the parallels of the bullshit spewed by characters in the script and by those leading the country.

At the same time, Boris Johnson was PM and doing an objectively terrible job. It seemed like daily there was a new scandal, a new set of lies, some new bullshit. I found myself frustrated and perplexed that anyone supported him or his government. I saw the parallels of the bullshit spewed by characters in the script and by those leading the country. A lot of advice you hear is to make a film about something you care about deeply. It can be hard to find a way into whatever that is. But seeing those parallels opened a door to mix the need to make a film and a subject I feel strongly about.

What tweaks did you and James make to that original script?

With the main body of the script already there, James and I set about broadening and retrofitting. Adding the political context, current affairs references and making it an expression of how we felt by giving it a purpose. The tale of Dolphins is mainly a reflection of Brexit. Seeing someone spout utter nonsense and fantastical promises, and then the disbelief as you see people fall for it. Left with nothing but a flat pint and cheap cigs, and then witnessing them lose that as well. It became about the villains at the top not being so different from those you walk past on the street.

The challenge of a performance-led piece terrified me but I was desperate to prove to myself that I could do it.

Other than context, the main thing that drew me to the script initially, was that it’s a ten page table scene of mainly dialogue, which I came to learn is notoriously one of the hardest things to shoot. Previously in commercials, I’d predominantly directed product-led videos or shoots with models. So the challenge of a performance-led piece terrified me but I was desperate to prove to myself that I could do it.

What were those challenges exactly?

Going in I was scared, it was my first time doing a narrative piece. I knew I wanted to take a big swing at it but I also knew in some ways I was kind of alone. Again with commercials, you’re always working with a client who can work with and against you, both approaches are helpful in their own ways, at the very least they’re a sounding board. But on this, I was my own client, there’s a tremendous freedom in that but also a big weight. There’s no higher power to check you on your decisions. Adding to this, there being a political nature to the film, you are always aware the finished product might not be received favourably. The good thing is that almost as soon as I got going in pre-production and I found people I know and trust to jump on board, that worry faded away.

What did pre-production consist of for you? Was it about working out the shooting style of a contained script?

In pre-production I spent a lot of time researching films like Lumet’s 12 Angry Men, listening to Ridley Scott talk about storyboarding every frame. I even reached out to ‘Twitter film school’ and tweeted some questions about blocking to some big-name directors, a few of whom generously took the time to reply. James Mangold spoke about Spielberg being a master of blocking and thinking about it as “triangles, not ping pong”. David Ayer wrote an in-depth note about how during a table scene in Fury, he experimented in rehearsal and then laboured with the actors on the shoot. He also touched on the shooting economics of the day. Edgar Wright gave some advice about directing performance, but some weird internet trolls popped up and he unfortunately had to delete the thread. It was all invaluable advice that helped shape my approach.

You mentioned that this was all conceived during Covid, did that impact funding for the film and the shoot itself?

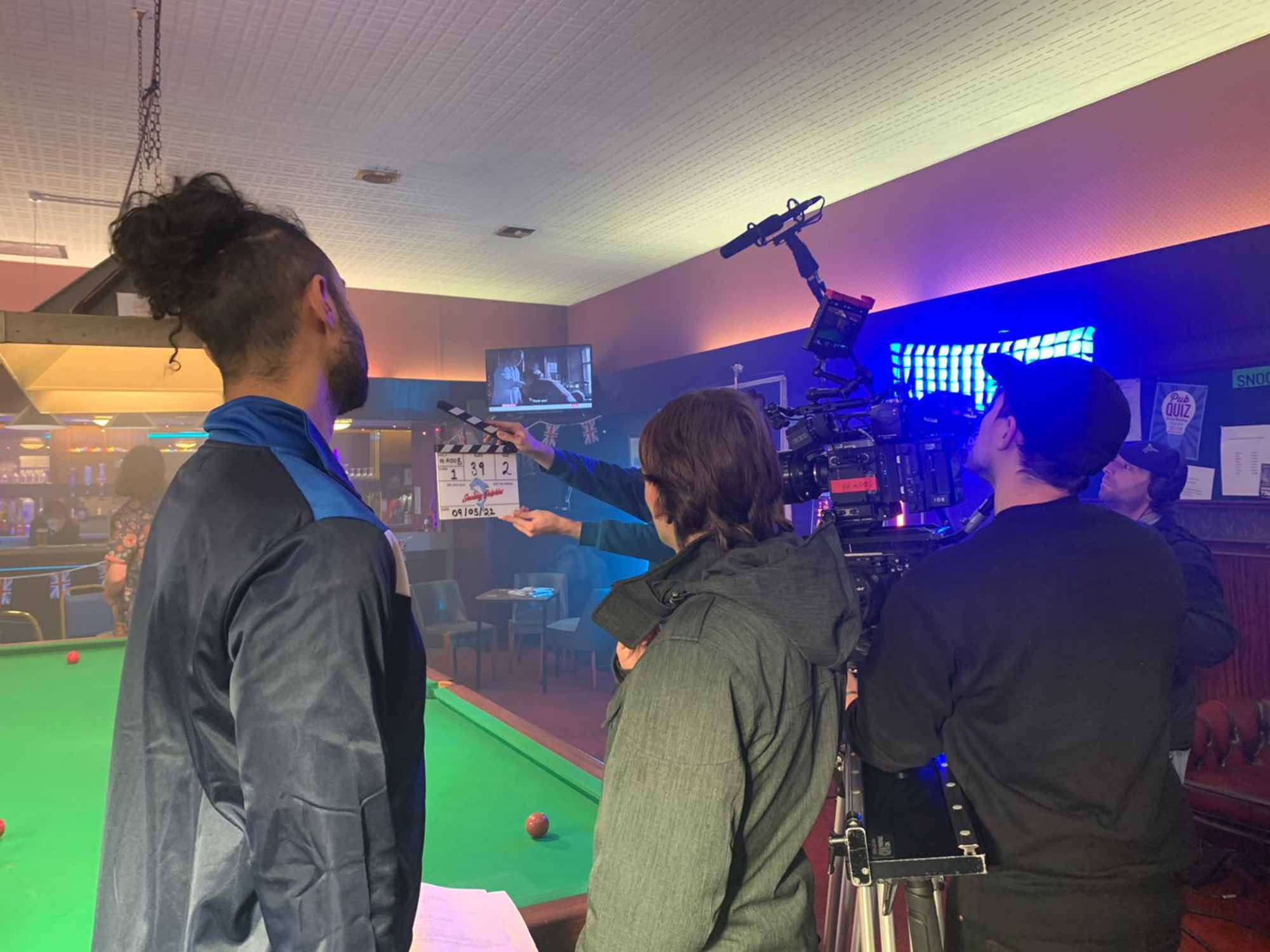

Funding is hard to come by at the best of times, never mind during a pandemic. I’d been made redundant due to Covid and decided to use the payout from that to fund the film. Financially, this was a terrible idea. There were a few false starts. We planned to shoot when the first lockdown lifted, but understandably everyone jumped back into work, as they hadn’t been able to for months. Then another lockdown was imposed so we couldn’t shoot. Our last chance to shoot was the last weekend before the tier system was lifted. Our location was a social club/pool hall that hadn’t been allowed to open for over a year. On the Monday it would open to the public seven days a week and we’d lose it. Thankfully the stars aligned, mainly thanks to my Producer Sophie Finnigan, who kept the ball rolling throughout and got everything where it needed to be.

The shoot itself is easily the most fun and alive I’ve ever felt on set. Our leads Tom Follows and Reuben Johnson had this fantastic chemistry straight off the bat. After a few conversations they understood their characters and take after take they nailed it. Tom Hardman on the opposite side of the table had limited lines but his presence and expressions both big and small did so much heavy lifting to push the story along and guide the audience through his POV.

I wanted to ask about the tone because there is a slightly absurd, elevated nature to the performances, what led you to that approach?

The tone was important, I’m not a fan of comedic moments where the actors deliver a line and then pull an inflated contrived look to sell the moment as funny. Humour is such a spectrum and the audience will sit across all of it. I wanted the roles played fairly naturally, letting the dialogue shine on its own. Letting the actors portray their characters instead of holding a sign saying “This is a joke”. Letting the absurdity of the story and character reveal itself always felt like the best fit. It’s been a joy sitting at the back with different audiences and seeing how certain lines land. That experience in itself, has been its own mini film school.

Armed with the advice that you referenced earlier, how did that inform the way you shot these characters?

I’ve been lucky to work with Cinematographer Dan McPake for years now, I couldn’t and wouldn’t have made this film with anyone else in the role. We’d speak about the need to build on the dialogue, and how we could use the camera to build and release tension at the right moment. You’ll notice as the tale is told, we gradually get closer and more Dutch as we reach the crescendo. But when Tony and Kevin are interrupted, the camera is pulled back and becomes more neutral. We looked to Terry Gilliam’s work on Brazil as well as Fear and Loathing for inspiration. In hindsight, those hallucinatory visuals of Fear and Loathing probably resonated more on a subconscious level after being cooped up during Covid for so long. But they were a great reflection of the confused head tilt I found myself doing, whenever I’d read or watch the latest delivering of Tory nonsense on the news.

I wanted the roles played fairly naturally, letting the dialogue shine on its own.

As David Ayer had advised, shooting the table scene was a labour. The script is a mostly continuous scene so I worked with the actors to find where the natural pauses, dips in pace and tension existed, and segmented the script from there. We purposely shot a lot of coverage, over and over again. Tighter wider, more Dutch, so in the edit we could build and release the tension when necessary.

The pub itself feels like a character too with the smokey, dusty atmosphere. Were you drawing on any specific inspiration for that? And did you and your team do anything to embellish the location?

My parents ran a pub when I was growing up. It was on a rough estate and had a lot of questionable and locally infamous customers. Even though I was young, I remember a lot of it vividly. The textures, the smell, the characterful faces. A lot of that inspired the characters, costumes and set design of the film. I wanted a Benidorm meets Salford aesthetic, where everything was clammy and coated in cigarette smoke residue. For the social club, we lucked out on the location, I wanted something that felt like Drexl’s brothel from True Romance, seedy with a lot of texture. It just so happened that after searching far and wide, the perfect location was a short walk from my house and had almost everything we needed.

Adding to that texture, for our main two characters, I said to Katie Wrigley our phenomenal MUA, that I wanted them to look and feel like they’d slumped in some kitchen at a never-ending afters, days of no sleep taking its toll on them. They both stepped on set and looked terrible, it was perfect! Due to the pandemic neither Dan nor Production Designer Ruth Jones had seen the location in person until the shoot day. After spending the morning lighting and dressing the set, I remember walking up to the monitor and seeing a wide of the pool room, and thinking, well this is exactly it. They both brought so much to the film with very little resources and almost no headstart. Never underestimate what a cheap neon palm tree sign can do for a scene.

You spoke about the need to find a rhythm with your actors and the tension and release of the dialogue. Was that an aspect of post-production that came together smoothly?

We were in post for just over a year, again down to the world opening back up and everyone needing to prioritise paying work. Editor Liam Acton latched on to the rhythm of the dialogue and the actors’ performance, just shaping the edit so well. Working with him, it was one of the first times I’ve been able to chat with an editor about the intention of a moment, point of view or comedic timing, it was so fulfilling. And with the coverage we got, there were so many ways we could cut a scene. After a while, you almost inherently go with the rhythm of the moment… triangles, not ping pong. Dan Moran graded the film, he took all that we shot, all the references I’d put together and just shaped it perfectly. He’s the best and I’m blessed he said yes to doing it.

With the coverage we got, there were so many ways we could cut a scene.

I learnt so much regarding sound on this, Max Brodie is just a dream of a collaborator, patient and knowledgable with me, adding layers and wanting it to sound the best. There’s a great bit towards the end, where at the exact moment Mark falls for the con, we hear the jackpot noise of the fruit machine go off. It’s a little detail but for me, it ties that moment and all that came before together perfectly. The biggest challenge with post-production was the news chyrons on the TV, the constant stream of government scandals meant that I had to keep updating them before realising that whatever I used would age very quickly. I went through maybe ten versions before ended up going for something more universal as the scandals weren’t going to stop any time soon. When we finally got them locked in and the film finished, Johnson resigned the next day, typical.

How long did it take then, as a project, from the initial revisit of the script through to the final lock? And what kit did you use on the shoot?

Script and pre-production six months with post-production lasting a year, stopping and starting on both due to the pandemic. We shot on a Red Weapon with Cooke anamorphic. No Drama who supplied the camera kit are just the best, so generous and eager to help, I couldn’t thank them enough. It’s been great seeing their logo on so many films on the festival circuit. They’re huge champions of up-and-coming talent. Drop City provided all the lighting and again the help these guys gave means the world.

What’s next for you, career-wise?

James and I are continuing to collaborate on new projects. We’ve got a follow-up to Smoking Dolphins already written. This time, it’s an ensemble piece set during the recording of a Question Time-like panel show, which examines the wider political spectrum of the country, keeping with the political satire. We’re in the process of trying to get it made, and although it’s still a short film, it’s much grander scope than Smoking Dolphins.

In the meantime, we’re also working on another short film that sits between those two in terms of size, which we plan to make in the interim. We realised through Smoking Dolphins that there is an audience for the type of work we want to create. In the long term, we hope to expand into longer-form narratives, and we’ve already begun working on ideas for that. I’m biased, but I think the scripts and ideas we have are phenomenal; the challenge is getting things made. Being in the North feels like a barrier at times, and a big goal is to learn about how the system works and how we can get these great ideas on screen.