Making his move into the director’s chair, Brooklyn-based Cinematographer Taylor McIntosh eschews narrative conventions for contemplative black and white short Swift River – a character study of a man who segregates himself from the world as he hunts for gold on an isolated river with only his dog and his thoughts for company. More of an observational piece rather than a traditional story of a man stuck in a transitional phase of his life, McIntosh joins us for Swift River’s online premiere and discusses how with a minimal crew and no script he sought to explore the compulsion for gold and solitude.

The choice of black and white here is a clear fit for the anachronistic practice of mining and panning for gold but I also noticed that you tend to favour black and white in your stills work too. What is it about working within a monochrome palette that appeals to you over colour?

I think that growing up in Maine really dictated my obsession with b&w. For me, it’s a region that’s defined by two polar opposites – our summers and our winters. Summer and parts of fall can be incredibly colorful but for the late fall, winter, and most of spring, Maine is suspended in this liminal gray light that can, and will, kill any saturation of color. We basically live in Ansel Adams Zone System for eight months. It’s a greyness that embeds itself in both vision and mind. Thoughts and ideas begin with black and white – life and death, good and evil, love and hate, natural and artificial, etc. It’s really this duality that I am interested in – so b&w feels like an innate lens to look through.

B&W feels like much more of a question where color feels more definitive.

With the b&w image, I can also ask questions about my reality, or the image’s reality, without using words – what is real and what is a dream? Is there a difference, and if so, does it matter? I guess for me, b&w feels like much more of a question where color feels more definitive, and I want my images to ask questions more than make statements.

What set the wheels in motion for this isolated tale of a man and his dog?

During the transition from spring to summer in 2014 I spent two months living and working with gold miners in Nome, Alaska. Previously, Nathan Nielsen (lead actor in Swift River) had sent me to an online forum where these miners had created a small community to inform others on when and where they would be working – if able-bodied people wanted to help out for their share in gold – then they were invited along. So I went. At the time, whether I knew it or not, observing these characters became a form of research which ultimately was the genesis of Swift River. I never asked these men where they came from, how they got there, or where they might go afterwards, something kept me from doing that. I just accepted that we were all present, together and individually, in that place, for that moment – and soon enough I thought, ”I want to see this on screen – I wonder if I can recreate it in hopes of understanding more”.

Observing these characters became a form of research which ultimately was the genesis of Swift River.

I started thinking about what I had learned in Nome, and how I could translate it. The idea of ‘story’ or ‘narrative’ never really crossed my mind and so I kept focusing on my observations and the idea of minimalism; which I have always been attracted to especially within the arts.

- What’s most important here?

- What information can we shave from the body while still leaving an identifiable skeleton?

- What are the necessary elements to keep an audience captivated?

Once I started asking these questions I turned to references that I thought might apply. I started reading a lot of Jack London, Ernest Hemmingway, and Albert Camus and I started watching all of the films made by Lisandro Alonso, Jia Zhangke, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Kelly Reichardt. Finally, I got to the point where I was either going to make something or not…

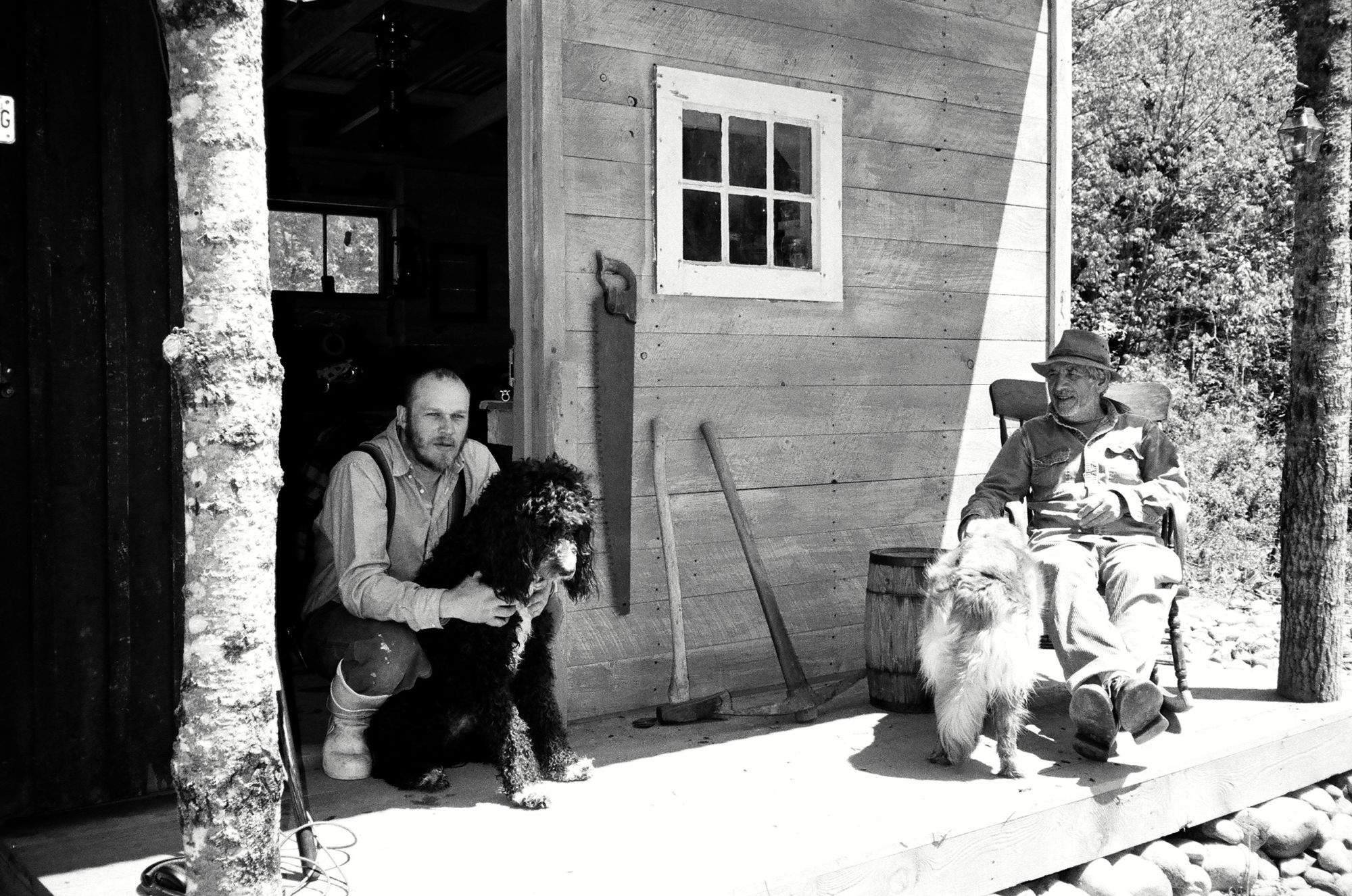

[Images by Ben Bishop]

How did you decide on your location?

I scouted the location for the film along the Swift River in Maine and went door to door asking people if we might be able to make a film on their property – the last person I asked was the only one who allowed the crew to work and live on his property. He offered up a small hunting hut with bunk-beds in it for the crew and let us build a small one room shack on the riverbed for the set – Nate also stayed and slept in the shack during production with his dog.

You shared cinematography duties here with two other people, could you tell us about the practicalities of that setup?

It really came down to the logistics of production being split up between summer and winter – winter was actually the first sequence that was filmed. Mack Fisher and I have been collaborating on films for nearly two decades now so naturally he’s the first person I turn to about a film or even an idea in its earliest of stages. I think what makes Mack such a talented cinematographer is not just his ability to light or compose but also the fact that he is such a natural born problem solver. The guy never says “No. We can’t do that”, instead, he’ll check his resources, think a bit, and always comes to the table with a solution that exceeds all expectation.

Mack and I shot the winter portion on a mutual trip home during the holidays to see family in Maine but when it came time to film the summer sequence we weren’t able to align – the river that we filmed on has a very narrow window during May where the water is either raging (with serious potential for flash flooding) or barely trickling. As soon as I knew Mack wasn’t going to be available – I called Kevin Dynia, who’s also been a long time collaborator. No matter what, Kevin is down for any sort of adventure, especially when it comes to filmmaking. He’s an incredibly optimistic and emotionally intelligent human – who is constantly reading and gauging the situation in front of him and reacting to it. This is the soil that his images grow out of so naturally they have the same curiousness and compassion and I knew this could only benefit the project.

Both Mack and Kevin are incredible cinematographers in their own right and each brings a crucial perspective to the table but I knew that I needed the two seasons to match visually, so my role became more of a moderator between the two styles to ensure the images didn’t stray too far from one another.

I’m presuming that the ‘non-narrative’ nature of the story meant that you could take a more free flowing approach to production and the subsequent edit.

Production was incredibly slim – most of the time we only had four people and one dog on set – sometimes there was a total of six. There was never a script for the film – at the time I thought it might kill some sort of artistic intent but I don’t agree with that anymore. I think a script is incredibly important – not so much for the director but for overall communication with crew. Instead, the crew and I freestyled everything for two full weeks. We would shoot in the morning, take a long lunch break around noon, and shoot some scenes from the afternoon through to blue hour. Then after dinner we would all transfer footage, watch dailies, and discuss what to shoot the next day. Throughout the whole process, I always kept the same central idea close; these men who had fallen off the face of the Earth and landed on a beach in Alaska to mine gold. Does there always have to be a reason or can things just be accepted for what they are?

The idea of ‘story’ or ‘narrative’ never really crossed my mind.

We didn’t have many options when it came to a camera and glass so we rented a locally owned RED Weapon with Zeiss CP2s. During post, and partly because of the workflow, I really began to dislike the look of this hyper-digital/sharp footage and felt like we had made the wrong decision but I slowly started to regain my trust in it once we got it into the hands of the colorist, Mikey Pehanich at Blacksmith, who helped to show me of its potential uniqueness.

The entire time we thought we were aiming toward making a feature – something long and poignant – but it wasn’t until the edit that I realized the film would never live any sort of life if it were 70 minutes so I just started chopping, reorganizing, and thinking. The end result is this: Swift River.

A significant portion of the Swift River’s effectiveness rests on actor Nathan Nielsen’s largely solo performance. What were you looking for what casting that role and how did you guide his performance especially in the absence of a script?

Nate and I have been good friends for maybe fifteen years now – he ran my father’s cabinetry shop for years and subsequently was my boss for a few summers during high school and college. At some point I learned about all these season-based activities that Nathan practiced – like tapping trees and making maple syrup, dredging for gold in the rivers, etc. and I asked if I could follow him around with a camera for a couple weekends each season for a school project. He agreed, and as soon as I had a camera on him I realized how just how incredible this man’s presence is when he’s working and thinking. After that project I never really stopped thinking about implementing that stoic nature in a more fictional role – so Swift River was really built around him.

During production I would give him tasks to complete and decisions to make during different takes and we would roll the camera for sometimes up to twenty minutes – long enough for him to forget about the camera and start focusing on his work. It was magical to watch this happen. My process is inherently discovery-based, and a lot of times once the barriers were down and Nate inhabited the scene he would just do his own thing – move wherever he wanted, sit and have a smoke, walk off camera to finish another task, etc. These little moments became some of my favorite parts of the film.

While minimal, there’s a portentous air to the film’s music, how did you arrive at that final score?

Jeff Melanson has this mind that can think in two directions at the same time. He brings an insanely strong intuition into not only his music but also his cinematography. The man is a double-edged sword. Without fail, every time I see his images working together with his music I’m thrown into a state of awe (for reference, check out anything he has made with Voyager and director Charles Frank, Henry Busby, or Lauren Rothery) so naturally I didn’t feel the need to direct him.

The only credit that I can take for the composition is that I handed him the drawing board and presented the challenge of reacting to the imagery, tone, and pacing with music. I don’t think we had rules or guidelines or even pre-conceived ideas – I just let him freely interpret what he saw and felt. What you hear now is incredibly close to his first pass. I was blown away. He legitimately gave the film its heartbeat; somehow he had figured out a way to narrate the film with an inner monologue of music.

Swift River marked your narrative debut, will we see you slipping into the director’s chair again in the near future?

I hope that this is just the beginning – there’s so much that I want to explore through directing. I tend to keep a dozen or more projects going at the same time – which can definitely deter me from finishing any one specific project but I just have to be patient – I’ve never been one to force anything.

On a whim, Scott Lazer and I spent a week a week observing the Storm Area 51 gathering that happened in 2019, which resulted in a film called Visitors. We lived together in a van in the desert and just filmed anyone or anything that would permit us to. We were less interested in the gathering as an event and instead tried to piece together this puzzle of characters that came together on the edge of society. It was a pretty weird moment and I think that comes across in the film. I like when that happens – when the experience of making something is instilled in the thing itself. Visitors should be released by the end of June or July.

I like when that happens – when the experience of making something is instilled in the thing itself.

Nico Bovat is also wrapping up another documentary project that I shot with her in 2019 titled Roomates. It’s an incredibly intimate portrait of the relationship between Nico’s father and her grandmother, as they get accustomed to living together under the same roof. Roomates should be released by the end of the year.