The word home evokes a sense of belonging, a place where one can feel safe and seek shelter from life’s storm but for a multitude of people all over the world, it is instead a place rife with trauma, painful memories and hurt. This type of unsettling upbringing and the knock on effects that reverberate through future life is something filmmaker Luke Brookner, co-founder of production house Sticker Studios, knows all too well and wanted to explore in his short Home. Centred around a young man desperately grappling with his younger life, Brookner moves between past and present with a fluidity and ease reflecting the overwhelming chaos and confusion coursing through his protagonist as he tries to separate the man he is now from the young boy he hasn’t yet left behind. Home is a tender and authentic exploration of how we define ourselves based on our past and the incredible strength it takes to move on to live for the future. As the film premieres on the pages of DN, Brookner speaks to us about the intense collaborative script writing process, how he visualised the fragmented nature of repressed memories and using different film stock to embody the past and present.

Is the film born of personal experience?

I grew up with my Auntie after having lost both my parents to cancer by the time I was seven. In my adult life, I struggled with relationships, identity and a sense of belonging. Home for me was not always a happy place and I wanted to create a film that explored some of the challenges that people who have grown up in care or in unconventional households experience. It was an exploration of what home means and how to create a happy home in your future if you haven’t experienced one as a child. Although my experience was unique I wanted the film to be universal. I never wanted the film to be autobiographical but more a representation of different backgrounds and experiences.

Home for me was not always a happy place and I wanted to create a film that explored some of the challenges that people who have grown up in care or in unconventional households experience.

Where did the idea for using the power and strength of poetry come from in the scriptwriting process?

I took a first draft to a charity I was working with, Drive Forward Foundation (DFF), who help young people in care find work opportunities. We ran a focus group and talked about our experiences. After which, King Sol Simpson and Tanisha Frazer, who I met for the first time in that focus group, stayed on and advised on the script eventually becoming executive producers on the project. We all shared the experience of how an unsettled home can make you doubt all your choices in future, even when things are stable, happy and good for you. That was something King, Tanisha and I all had in common. Unsettled homes meant that all of us had a distrust in things that were good. And whenever something was too comfortable we left and made decisions that weren’t necessarily in our best interests.

The scriptwriting process was collaborative. Hours in Nandos spent conversing about our upbringings, experiences and our emotions. At different times in all of our lives, we had all written poetry as a means of expressing an unexplainable feeling from trauma that we felt we couldn’t express in conversation. We liked the idea of this being a character trait for the protagonist Jaden. He couldn’t explain his childhood, his trauma and his emotions, instead the audience and his girlfriend Faye could only learn how he really feels through his poetry. In terms of the actual words we used, King, Tanisha and I all wrote poems about our relationship to home and King’s poem was the one we used in the film.

We had all written poetry as means of expressing an unexplainable feeling from trauma that we felt we couldn’t express in conversation.

Those blisteringly painful flashbacks are so visceral and carry the narrative, how did you find the right balance to explain this young man’s pain but not drag it down?

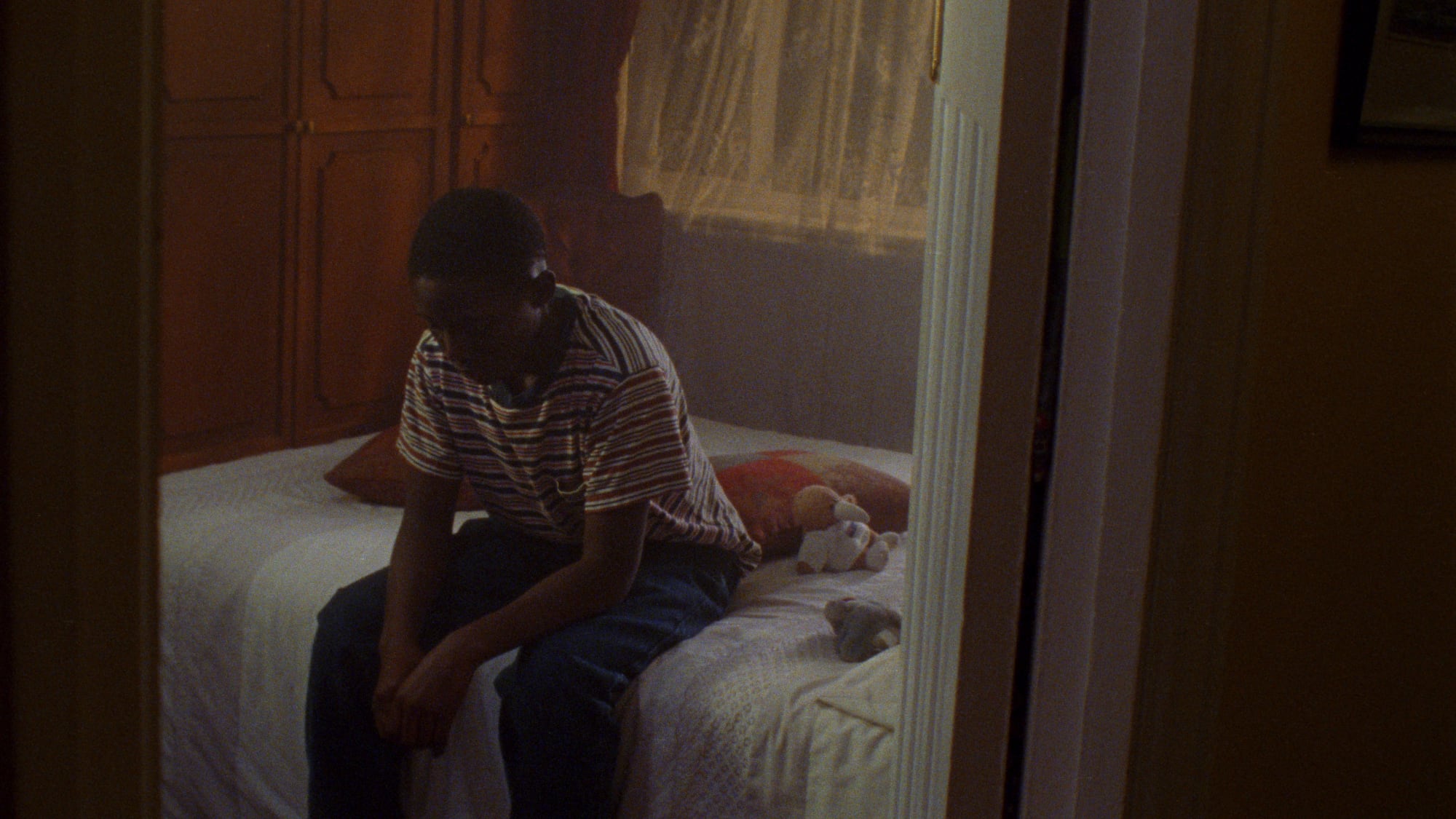

With this story there were always two important components. The present day narrative where we see Jaden’s about to become a father in a world he doesn’t feel at home in. And the past, a background of care, distrusting relationships and abuse. We wanted to make sure Jaden’s past was communicated but it didn’t interrupt or slow down his present. We wanted the nature of the flashbacks to reflect the reality of memories. Memories have a certain translucent and fragmented quality in your mind, they don’t come back fully formed, traumatic memories are usually repressed, to the point that even trying to remember them is a struggle. This idea of how we deal with and remember trauma, and how fragmented and distant memories can feel, was really important for the nature of the flashbacks. What we wanted to create was this feeling of repression throughout the film, the flashbacks reveal themselves incrementally throughout and then near the end of the film it all comes flooding back uncontrollably and cathartically.

We wanted to make sure Jaden’s past was communicated but it didn’t interrupt or slow down his present.

Your range of locations all feel so lived in and accurate to the story.

It was a mixture of being clever with what we had and ensuring we could be resourceful in the locations. We had a very talented production designer in Elena Isolini but our producer George Telfer and the team did a group job of finding locations that really fit the brief of what we were looking for. We didn’t have endless resources so the foster carer’s house, the bedrooms for the childhood flashbacks and the mum’s house were all shot in the same location. We also ended up using all the homeowner’s furniture and their family photos.

Producer Geroge Telfer’s experience and roster of films fit perfectly with your story. How did his knowledge influence the production?

George was an incredible sounding board both in script development, production and on the shoot days. This was my first narrative project and before we went into pre-production I remember him saying, “We can’t shoot this script.” This led to an invaluable six months more of script development. His knowledge of story, locations and the characters went over and above what I have experienced with a producer before. Everything was story first, performance first, constantly pushing for the best of the creative.

The film moves between periods – 2 years ago, 10 years, and 20 years ago – so we wanted a visual way to guide the audience through the story.

How did you arrive at the decision to shoot 35mm for the present day and 16mm for the past?

I’m always drawn to film, the idea that performance is finite and it gives the project a certain realness. It’s not right for every project but I feel there’s an authenticity to it. It grounds a film in a certain quality and texture, which is exactly what we wanted to do here. The other function of 16mm and 35mm was to distinguish between timelines. The film moves between periods – 2 years ago, 10 years, and 20 years ago – so we wanted a visual way to guide the audience through the story. There’s a nostalgic quality to 16mm which felt right for the flashbacks. We wanted the picture to feel textural, real and authentic so 35mm was perfect for the present day.

The pace of Home and the blend of flashback, present and that rapid fire scene are all so well realised.

On the page it felt like a 50:50 split between past and present but as we were editing it was clear that the power was in giving away less and less every time. We knew the trauma and what we wanted to convey with Jaden’s story and I think we were conscious of losing important story beats. What happened over the editing process is we realised that you only really needed to know two things in his past for the story to work: 1) he had a traumatic childhood 2) he found it hard to relate to home. Once we realised that the remaining past story was texture, it gave us the freedom to cut it even shorter.

You’ve created an impressive growing collection of films to date, what can we expect to see from you next?

I’m currently writing a few projects in development with George and a project called Heirlooms about men’s mental health which I’ll be shooting next month.