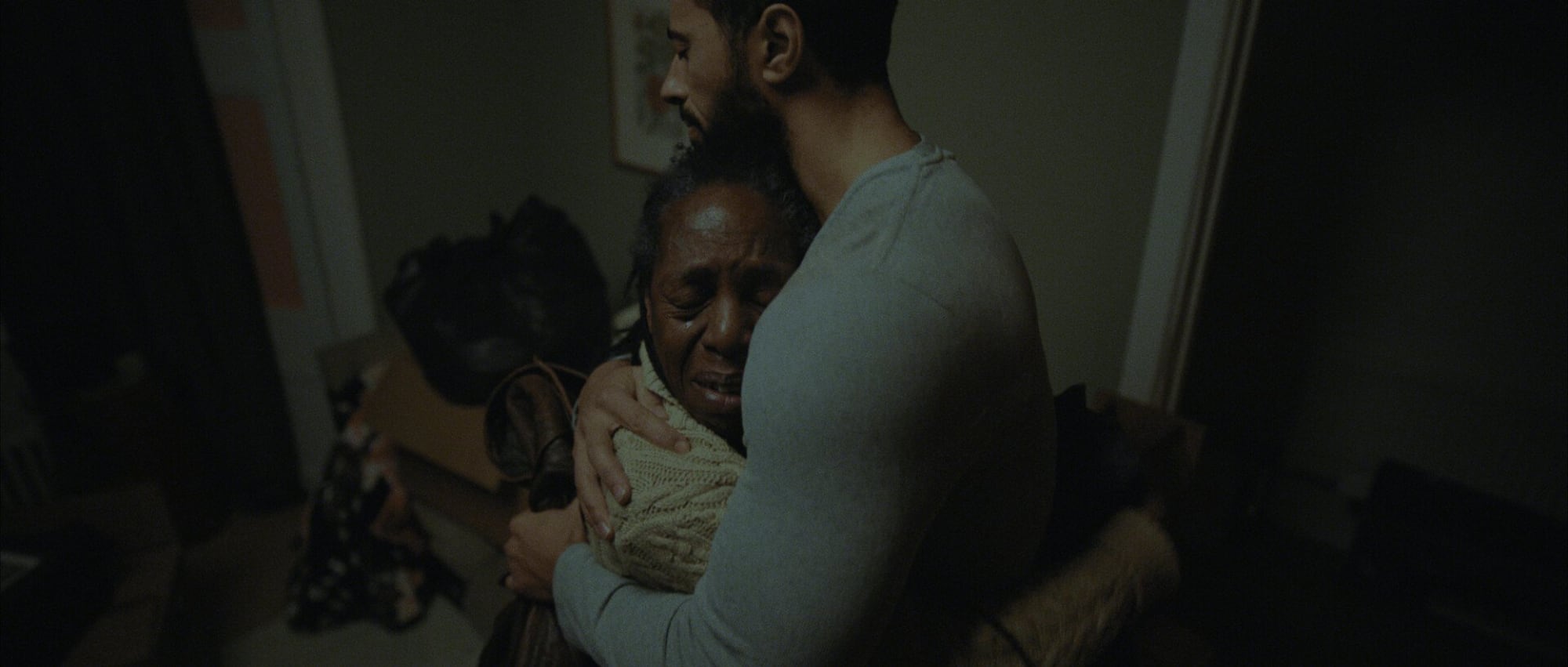

The best and worst moments in a family’s lifetime can often be traced back to one place: the home. Birth, death, happiness, tragedy; it can sometimes feel like everything is contained within its four walls. The home has an immense cinematic power too, able to conjure all types of memories and associations while physically resembling sitting in the screen itself. In Ajuàn Isaac-George’s Snowfalls in the Summer, the same living room plays host to a decade spanning series of dramatic events in the life of one family, moving effortlessly between the 80s and the present day, at times feeling like a feature film condensed down to its most essential moments. With keen blocking, smart edits between the eras and a great ear for the kind of lines that would ring in your head throughout the years, the result is an emotionally vibrant exploration of how regrets can pass through the decades as well as the importance of holding onto the more important things. As Snowfalls in the Summer heads out on its festival run, we talk to Isaac-George about writing detailed biographies for the characters, managing complex transitions and the benefits of shooting on widescreen.

This feels like a very personal story, was this a film you simply had to make? How supportive was the BFI Network in realising your vision?

For me, the best ideas come all at once. Fully-formed but still needing to be fleshed out. I see or hear something that strikes a chord and it brings an idea to the forefront of my mind. I’ll usually know immediately if an idea has legs or not. In the case of Snowfalls, I overheard a phone call (the dialogue is actually in the film) and immediately had the idea. Because the idea came from an authentic place, I felt it was something I had to make.

The BFI, especially my Exec Aaliah Simpson, were very supportive. They believed in the story and the experimental way we planned to shoot it and pretty much let us get on with it but offered guidance when we needed it.

One of the first things I do before the second draft is write detailed character biographies.

There’s such richness to the characters and the story. It certainly felt like there was more than could be expressed in just this short. Did you write bigger backstories for your characters?

100%. After writing the first draft, which I do with as little planning as possible, one of the first things I do before the second draft is write detailed character biographies. These usually include the life history of the character up until the point we meet them in the film. When I do the second draft, I then change and shift things based on the more fleshed-out personalities of the characters, constantly asking myself: “Would this person actually do this?” Probably 85-90% of what’s in the bios doesn’t make it on screen but it just helps to make things feel more alive and give the characters more depth. Bits and pieces of characters are always based on people you know in real life, which also makes them feel richer.

There’s a lot of sadness here, but also a great empathy that comes through understanding family dynamics well. Was there a lot of personal inspiration in the screenplay? What was it like getting the balance right?

Yes and no. It’s hard to make films, especially family dramas, without them being personal, but there’s also a risk of alienating a wider audience if you go too personal. Why should anyone else care about something only you can understand/relate to? For Snowfalls I wanted to make the emotion and heart of the film personal but craft the story in a way so that anyone who watches it can relate. We wanted anyone watching to recognise their own family.

What was the casting process like? How much did you tell your actors about the backstory and how much preparation did they do to get into that familial headspace?

A lot of credit here has to go to Casting Director Hannah Williams. Because there was such a big cast for a short, she came into the process earlier than you otherwise might usually expect. Because I like to work a bit more off-the-cuff, always looking for naturalism and nothing too refined, a big thing for Hannah and I was to cast actors who we felt strongly resembled the characters’ lived experiences. Although there are a few really seasoned actors in the film, there are also a few who’ve never acted on screen before. Once cast, I asked the actors if they’d like to see the biographies I’d written, as sometimes they might prefer not to. Although for Snowfalls because we were short on time, the biographies were a useful shorthand.

I’m a believer that you should only speak to your actors if you really have something to say.

We then had a sit down where we didn’t read lines, but instead chatted about the different relationships and history of each character. On set, I’m a believer that you should only speak to your actors if you really have something to say, rather than constantly feed information. A lot of the actors found the performances themselves and I offered the last two to three per cent in the right direction when it was needed.

It’s remarkable how much mileage you get out of this one space. How did you think about the set-up? Was it a set or did you find a real flat?

Producer Alessia Lendrum and I did look into a set build but based on the budget it would have been too expensive. Because of that, we decided to film on location and find a house that best resembled the one described in the script. The main thing we looked for was somewhere with enough space to shoot in the roaming fashion we wanted, somewhere that would be easy to redress, in terms of flooring and wallpaper, and also a space that had depth, so the film didn’t end up feeling claustrophobic. We ultimately ended up filming in an old Victorian house in East London that we were lucky to get. Set Designer Isabel Alsina-Reynolds was then able to transform the house at the end of the day, taking us through from the 80s to the 2020s.

I love the transitions in camera movement and editing, moving between space and time. How hard was it to match the shifts correctly? Was this something that you baked into the screenplay or was it realised more through editing? How much rehearsal was there?

The transitions were very much baked into the screenplay and the plan was always to shoot in a non-linear way. The Director of Photography, Jasper Enujuba, and I are good friends, so even before the film was funded, from a much earlier draft of the script, we were discussing how to shoot the film in a way to make it feel like a stream of consciousness.

By shooting each scene in one take, subconsciously, when there is a cut, the audience knows we are entering a new period.

When conjuring an image of what a memory could look like in physical form, it’s usually something flowing and free, almost like a river. Because of that, after a few different ideas, we came up with the concept of shooting each scene with a constantly moving camera, even if it’s not noticeable to the naked eye. We wanted it to be very subtle, so as not to call attention to it. By shooting each scene in one take, subconsciously, when there is a cut, the audience knows we are entering a new period. On the script, you can put the year in the slug line, but on screen, without constant titles, it had the potential to get a bit messy. Shooting the way we did meant we were able to utilise the full power of the cut to take us through time. To get across the idea of the house bearing witness to different memories and emotions across time, we often opted to end a scene in terms of the physical space where the next scene began.

Steadicam Operator Gary Kent was also on hand to offer up great suggestions about where he felt we could refine some of our camera moves. In the end, it really was a collaboration between Jasper, Gary and myself. Above everything else however, even with some of the more choreographed scenes, and stylised transitions, it was always designed to serve the story. In a film that centres around memory, space and time, this gives you a lot of options to play with. We’d rehearse every scene maybe five to six times before rolling and I’d say we probably averaged about six to seven live takes per scene.

Shooting on widescreen is very interesting for a film shot in the same place. What was the rationale behind this decision?

The first reason for the DOP and I was to differentiate between each of the time periods, 80s, 90s and 2000s. Each period is shot in a slightly different format just to give it a different feel. Secondly, it was so that the house felt more omniscient, like it was ageing alongside the family and bearing witness to all these different emotions and situations. For a lot of people, the same house where they host a funeral wake might be the same house where they host a graduation party and we wanted that to come across. By shooting on widescreen, it brought greater attention to the subtle details in the background that shows the passing of time – the wallpaper, the piano, the sofas – that we otherwise might have missed.

Each period is shot in a slightly different format just to give it a different feel.

I’d love to talk about your inspiration as well. I was mostly reminded of Terence Davies here, in the sweep of time and the excellent use of one family unit. Were there any films or filmmakers that influenced you?

You’re not the first person to mention Terrence Davis but I’ve actually not seen Still Voices, Distant Lives, which is the film I think you mean. After hearing about the similarities with Snowfalls I deliberately avoided watching it! I still haven’t seen it but it’s on the list and I’ll probably check it out soon. We didn’t look at any cinematic references for this film, mainly focusing on old photographs for the feel and texture of the time periods. The HODs and I just chatted about how we wanted people to feel watching it and went from there.

That’s something I’ve been thinking about more lately and have found myself using fewer and fewer references and avoiding them altogether if possible. The main reason for that is I’m trying to shoot each film based on the heart and uniqueness of the script, rather than leaning too much on other films. In terms of my own influences, there are too many to name!

The music feels like a key part of the film’s power, helping the transitions work excellently. Tell me about your collaboration with the composer!

Snowfalls was the fourth film Composer Ioana Selaru and I had worked on together. Because of that, we have more of an honest relationship. If I don’t like something she’s done I will tell her and she’ll tell me if she thinks an idea of mine is stupid.

The main thing we wanted was for the music to act as a subconscious link between time periods, creating a sense of familiarity within the audience that spanned across decades. After trying some much more experimental versions of the score, we stripped back most of the elements and ended up using a very simple chord progression, altering the pitch slightly based on the emotion of the scene and what we needed. Ioana is a trained violinist rather than a pianist so because of that, what she played on the keys was more organic and raw than what a trained pianist might have played. Once we did have a cut, Ioana and I sat down, and she just translated how she felt watching the film through the keyboard and we refined it from there. Something we did try to make sure of, was to only use music where we felt we really needed it, rather than using it as a crutch.

We initially spoke to you as Snowfalls in the Summer was setting out on its festival journey. How did you find that experience and what were audiences’ reactions to the film’s themes of family, loss and love?

The festival circuit was an interesting one. The film had quite polarising reactions I think, in that people really loved it and absolutely empathised with the themes or that they were a bit removed and felt it was style over substance. I think for me, what was more important was getting the film in front of the right people on an individual basis and for the most part, I’ve managed to do this.

What projects do you currently have on the boil?

At the moment, I’ve got a few different feature projects at various stages, some still in development, others actively looking at routes into production. The goal for me is to shoot a feature in the next 12 months.